Films that explore trauma interest me greatly. Not just because they, of course, expand the aesthetics of the horror genre; but for how they examine the connections between body and mind under duress. As Halloween approaches, it would seem an ideal time to discuss some memorable films in this category.

I should, however, point out that films will be excluded from my consideration on two counts:

- A conclusion that suggests absurdist comedy: such as Don’t Look Now (1973)

- The overuse of blood and guts for shock value: while this has become a kind of default setting for horror movies, I am drawn much more to films that do not rely solely on the visualization of horror, and leave it more to the viewer’s imagination.

The film I will now discuss features a horrifying scenario: a dentist as torturer. The fictional Nazi dentist is Christian Szell, known, at Auschwitz, as the “White Angel.” He extracted the gold from the teeth of the persons who were sent to the gas chambers. After the war, Szell went into hiding in Uruguay.

“Is It Safe?”: Marathon Man

(dir. Schlesinger 1976)

The opening scene, set on Yom Kippur in New York City, does, however, almost feel like absurdist comedy. After checking on Szell’s illicit assets that have been converted into diamonds and are kept in a safe deposit box, Szell’s brother leaves the bank. But his car stalls, blocking the way of an elderly Jewish driver. With an impatience that borders on the maniacal (not untypical of NYC citizens the film would have us believe), the Jewish man drives right into the back of the car, culminating in a full-on exhibition of road rage between the two. Engulfed by mutual hatred, neither can see the fuel-oil tanker in front of them—until it is too late.

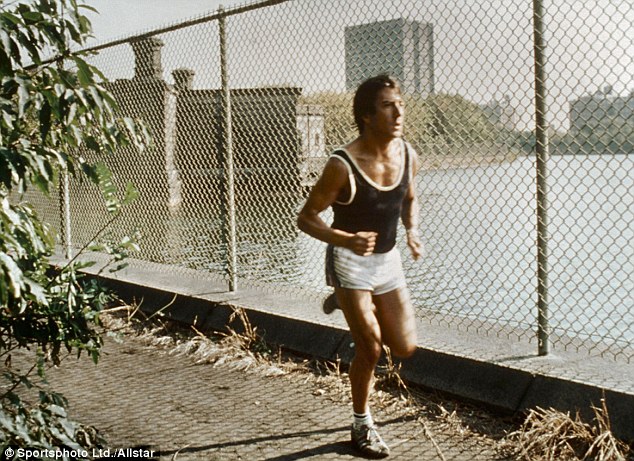

Cut to Babe, played by Dustin Hoffman, a graduate student in history, out on a run while sirens blare in the background. Focused on his marathon training, he appears oblivious to the drama taking place nearby.

Cut to Babe, played by Dustin Hoffman, a graduate student in history, out on a run while sirens blare in the background. Focused on his marathon training, he appears oblivious to the drama taking place nearby.

Marathon Man gives a heightened relevance to what Stephen Dedalus, in James Joyce’s Ulysses, says: “History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.” Babe is haunted by having witnessed, during childhood, the scene of his father’s suicide, a victim of the McCarthy witch hunt. His thesis aims to clear his father’s name, one point among many that distances Babe from his brother, Doc, whose acumen for making money counterpoints Babe’s idealism.

Two brothers from two historically opposed families. One now dead. One who is not as he seems: while Doc uses the cover of being an oil man, in reality, he does dirty jobs for the U.S. government such as serving as a diamond courier for Szell in return for Szell’s having ratted out his Nazi comrades.

His brother’s death having flushed him out of his hiding, Szell meets with Doc. They argue; Szell, played by Lawrence Olivier, may look physically frail but performs Szell’s ruthlessness with a clinical perfection. Concerned that Doc may double-cross him and steal his fortune, Szell stabs him. Doc makes it back to Babe’s apartment before dying.

This sets up the first encounter between Babe and Szell. Babe is tricked by Janeway, a government agent who is also assisting Szell, into being captured. Unaware that Doc died before he could tell his brother anything, Szell wants to know what Babe knows.

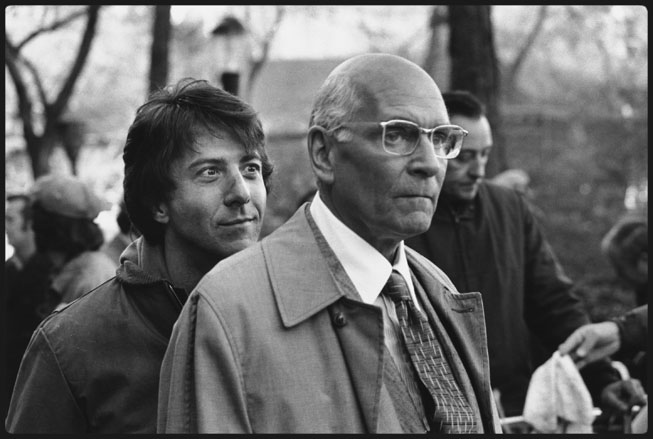

What next takes place showcases the profound differences between Hoffman and Olivier’s acting philosophies. An apocryphal story emerged that Hoffman told Olivier that he had gone without sleep in preparing for his role (in fact, Hoffman had been out partying all night). Olivier replied, “Try acting, dear boy.” Regardless, the differences intensify our emotional reaction to Babe’s endless bad dream, one from which he cannot wake. Hoffman gives a visceral—almost, at times, feral—performance: all sweat, nerves, and fear. In contrast, Olivier is businesslike and deliberate, casually menacing.

What next takes place showcases the profound differences between Hoffman and Olivier’s acting philosophies. An apocryphal story emerged that Hoffman told Olivier that he had gone without sleep in preparing for his role (in fact, Hoffman had been out partying all night). Olivier replied, “Try acting, dear boy.” Regardless, the differences intensify our emotional reaction to Babe’s endless bad dream, one from which he cannot wake. Hoffman gives a visceral—almost, at times, feral—performance: all sweat, nerves, and fear. In contrast, Olivier is businesslike and deliberate, casually menacing.

Aware that time is running out, Szell must be expedient. In his mind, it is simply a pragmatic decision to inflict pain, a mentality inculcated during the Nazi regime. Babe is innocent, but his brother has implicated him. Bound to a chair, Babe is now at the complete mercy of a desperate man who will do anything to get what he wants.

Szell asks a number of times, “Is it safe?” First, Babe takes the reasonable position, saying he doesn’t know because he doesn’t understand what the question is referring to. Then, trying to give the correct answer, he says, “Yes, it’s safe. It’s very safe. It’s so safe you wouldn’t believe it.” When that doesn’t work, Babe gives the opposite answer: “No, it’s not safe. It’s . . . very dangerous. Be careful.”

Babe is forced to open his mouth, as Szell probes with a dental tool and finds a cavity. Szell asks the question again. Babe starts to say, “I don’t know,” before Szell jams the tool right into the cavity. The screams of pain cause one of Szell’s henchmen to turn away, unable to watch.

is forced to open his mouth, as Szell probes with a dental tool and finds a cavity. Szell asks the question again. Babe starts to say, “I don’t know,” before Szell jams the tool right into the cavity. The screams of pain cause one of Szell’s henchmen to turn away, unable to watch.

Janeway then pretends to rescue Babe in another attempt to find out what Doc said before he died. It is clear that, as Janeway’s callous attitude reminds us, the rationale heard so often during the Nuremberg trials, “just doing one’s job,” is alive and well in American bureaucracy.

After Babe says that his brother didn’t tell him anything, Janeway brings him back to Szell. Stunned, Babe hears from Szell a fuller explanation of what his brother may have been plotting. When Babe still says he doesn’t know anything, Szell tells him he is going to drill into a healthy tooth which will be “infinitely” more painful than drilling into a diseased one.

From Babe’s perspective, we see the drill going in. The sound of a drill, the image blurs. Refocus on Szell’s face, an appearance of clinical detachment. Zoom into his eyes. Then on an overhead light. The screen fills with white light, as Babe’s screaming, when the nerve is hit, blends with the sound of the drill. We can only imagine, if we would dare to, what such pain would feel like.

Szell concludes that Babe knows nothing and orders him killed. Propped up against the hood, Babe waits until both of the henchmen are inside the car and takes off running. The camera focuses on Babe clad in pajama pants with blood running out of his mouth. His flight instinct sharpened by the endorphins kicking in and the stamina gained from his marathon training enable him to escape.

After eluding a set up, in which he kills Janeway and Szell’s henchmen, Babe tracks down Szell, carrying a briefcase containing the diamonds. He leads Szell, at gunpoint, onto the platform of an underground water canal. Symbolism is heavy in this scene, especially when interpreted through Freudian psychoanalytic theory. Babe holds a pistol, the same one with which his father used to commit suicide. Szell has a concealed knife, which he previously used to kill Babe’s brother.

Their final confrontation is somewhat bizarre. Szell attempts to placate Babe by opening the briefcase and placing it in front of him. Babe shows his contempt by picking up handfuls of diamonds and throwing them at Szell, taunting him by making him an improbable offer: Szell can keep as many diamonds as he can swallow. In retaliation, Szell baits Babe by insulting his father and brother. Predictably enough, Babe loses his composure and ends up dropping the gun. But Babe is quicker than Szell, throwing the briefcase down the stairs of the railing to distract him. Szell, in pursuit of the briefcase, trips and falls down the stairs impaling himself. As Szell’s body slips into the water, Babe leaves, ignoring the partially full briefcase.

While some of the moralistic overtones dissipate after Babe throws the gun into the water outside, the film is insistent in its argument that the brutal struggles of history repeat themselves. And loss exponentially increases: Babe’s blackened front tooth signifies all he has been through, but what, finally, is the ultimate horror that Marathon Man forces us to confront is that historical trauma exceeds any sense of individual containment. Thus we are never safe.