HALF HEAVEN, HALF HEARTACHE

or

HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE TEENAGE IDOLS

The King was dead.

Or at least, had abdicated.

In his absence came a new generation of teen beat idols. For many, they weren’t idols at all: they were the boogeymen of rock ‘n’ roll — pallid popsters who roamed the earth as mediocre dinosaurs in the dark days of the pre-Beatles era.

Let’s take a step backwards. I doubt I need to tell anyone about the impact that Elvis Presley had on culture of the 1950s and beyond. But let’s just keep in mind a few things: the sheer dirtiness of what it was that Elvis was doing. The man’s music and his live performance persona were obscene, vulgar, sexual, maybe even heretic or subversive.

Lester Bangs once wrote that:

“Elvis alerted America to the fact that it had a groin with imperatives that had been stifled. Lenny Bruce demonstrated how far you could push a society as repressed as ours and how much you could get away with, but Elvis kicked “How Much Is That Doggie in the Window” out the window and replaced it with “Let’s fuck.” The rest of us are still reeling from the impact. Sexual chaos reigns currently, but out of chaos may flow true understanding and harmony, and either way Elvis almost singlehandedly opened the floodgates.”

The top rock stars of the late ’50s were all Presleyesque (Preslesque?) in their commitment to energy and raunchiness. Jerry Lee Lewis, the incestuous wild man of rock ‘n’ roll, beat away songs on his hot piano with an almost-religious intensity — his Pentecostal upbringing darkly reflected and repurposed on blatantly sexual songs, songs with names like “Breathless” and “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On.” African-American singer-songwriter Chuck Berry almost single-handedly defined the electric guitar as the lead instrument of rock music in rapid-fire hits like “Johnny B. Goode” and “Too Much Monkey Business,” while Little Richard took Jerry Lee Lewis’s heretical fervor and combined it with a sexual ambiguity. Buddy Holly lacked something of the pure vulgarity of the other artists, but his innovative songwriting prowess felt just as fresh and energizing as the others’ gleeful tastelessness.

And then it all stopped.

Not all at once, actually, though in retrospect it seems staggering how quickly it all fell apart:

Elvis got drafted, and was inducted into the Army on March 24, 1958, preventing him from recording any new albums, singles, films, or television appearances. He would not be discharged until March of 1960, and when he came back, his music seemed either neutered or matured, depending on who you asked. Jerry Lee Lewis created one of the biggest scandals in rock history when the news broke in May 1958 that he was bigamously, incestuously married to his pregnant 13-year-old cousin, leading to his blacklisting from the popular music industry. Buddy Holly, along with rockers Ritchie Valens and J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson, died in a plane crash on February 3, 1959. Chuck Berry was arrested in December 1959 for violating the Mann Act and had to serve jail time. Little Richard experienced a “Road to Damascus” moment and turned his back on rock ‘n’ roll to become a preacher.

A newer breed of rock stars emerged to fill the void. They weren’t the King — but neither was the King at this point. There are many we could look to to define this era, but only five really stand apart: Ricky Nelson, Gene Pitney, Dion Dimucci, Del Shannon, and Roy Orbison.

What did they have in common? For one thing, they were singers, first and foremost. Unlike Jerry Lee Lewis, Chuck Berry, or Little Richard, instrumental virtuosos all, these newer pop idols placed a much greater stress on the vocal performance. Some, like Pitney or DiMucci, rarely played any instruments at all. This emphasis on vocals highlighted their connection to Elvis Presley, and demonstrated how these young men were being positioned as the new heirs to the King.

Roy Orbison was the defining figure, the only truly transcendent artist of the pack. A second-string rockabilly hanger-on who had scored a minor hit in 1956 with dance novelty “Ooby Dooby,” Orbison was out of place in the first generation of rock and roll. He lacked the sexual frenzy of his peers, at least in terms of demeanor and stage presence. He stood still, almost motionless on stage, and unlike the trim, lithe Presley, he stood awkwardly, looking like exactly what he was: a gawky country boy with big glasses. Orbison did not find his niche until 1960, when he wrote and recorded “Only the Lonely (Know the Way I Feel Tonight).”

Already, from the title alone, we can tell we’re not in “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” territory anymore. It was a melodramatic rock ballad that combined, in an unprecedented way, rock ‘n’ roll with traditional vocal pop music (think Bing Crosby), and even classical and opera, into a style of music that has been much imitated, but never bettered. Utilizing choir-like backing vocals, the ghostly production of Fred Foster, and lush strings, “Only the Lonely” was a showcase for Orbison’s unparalleled voice. Some have called Orbison the best singer in rock history. He is almost certainly the most distinctive. At times sounding more like an operatic tenor than a rock singer, though far stranger than either, Orbison’s voice was like “the cry of angel falling backward through an open window” according to Dwight Yoakam, a voice wavering through octave after octave with a frightful fragility that masked the supreme control Orbison possessed over it.

Lyrically, “Only the Lonely” was a decidedly darker piece of music than the rock hits that preceeded it. Elvis’s ballad “Love Me Tender” may have been vulnerable, but “Only the Lonely” was depressive, an empathetic portrait of a man’s world defined by his sheer solitude. “Only the Lonely” had the noir-like loneliness of “Heartbreak Hotel,” and the sensitivity of “Love Me Tender,” but it also possessed a big, epic sound that dwarfed both of those songs in scope. Audiences responded to it an equally big way, sending it to #2 on the Billboard singles charts.

The Orbison body of work had begun. With followups like “Blue Angel,” “Love Hurts,” “Running Scared,” “Crying,” and countless others, Orbison expanded and deepened the world of loneliness and pain he created on “Only the Lonely.” The titles say so much. These records don’t boast names that promise dancing and sex, like “Breathless” or “All Shook Up.” They paint portraits of sad, isolated individuals, broken up inside and broken away from the world. They speak to anyone who has ever felt alone, like they were the only person missing out on the pursuit of happiness. Orbison’s magnum opus might be 1963’s “In Dreams,” an epic of composition and performance; the perfect pop song that could only have been written by a man who had the genius to ignore all the rules of pop songwriting.

Without repeating a single musical section, “In Dreams” tells the progressing story of a man drifting away to sleep and enjoying the warmth and company of his love in the dream world, before waking and realizing that he has awaken alone. The song ends on a suitably depressing note, not with a moment of reconciliation or renewal, but with a sad acceptance of the unchangeability of the singer’s fate.

“It’s too bad that all these things /

Can only happen in my dreams /

Only in dreams /

In beautiful dreams.”

Other members of this generation lack Orbison’s songwriting genius, nor can they match his vocal abilities, but they possess similar attributes and strengths, and unique advantages. Gene Pitney was probably the best singer next to Orbison, and had a more conventionally acceptable voice. Pitney, a vocal sensation who owed a great debt to older generations of vocal pop music, and probably could have been a very successful crooner had he been born ten or fifteen years earlier, was probably the least “rock ‘n’ roll” of the five highlighted here. But that is not to disparage his talent and work in the slightest. His songs were some of the oddest of the early rock era, boasting unusual premises and aesthetics that made him stick out from the pack. One of his earliest hits, 1961’s “Every Breath I Take” was emphatically strange. Boasting scatting back-up vocals that complemented Pitney’s leading falsetto, and a string accompaniment that seemed to be only tangentially related to what the rest of the band was doing, “Every Breath I Take” also featured some very odd lyrics, avoiding the typical romantic cliches of “I want you, I need you, I will never leave you,” and so on and so forth. Instead, the speaker promises his love that he will never tell her he love her, but that instead his gratitude will only be “with every breath I take.”

“Mecca” used Orientalist, pseudo-Middle Eastern rhythms and arrangement (including what is presumed to be an Indian fakir’s flute) to tell a story of “East meets West” between a young boy and girl in love — “‘Cause that brownstone house where my baby lives is Mecca to me.”

Similarly to “Mecca,” Pitney’s hit “Town Without Pity” (the theme song to a 1961 film about gang-rape and murder in occupied Germany) told the story of young lovers kept apart by a cruel society that doesn’t understand them.

“How can we keep love alive /

How can anything survive /

When these little minds tear you in two? /

What a town without pity can do…”

Pitney’s belting voice — at times soft and childlike, at other times loud and declamatory — could make any story in any song sound like a great melodrama. If Orbison’s body of work was one that told stories of solitude, the consistent theme of Pitney’s songs was the denial of great love. Lovers were kept apart by small-minded family members and society types (“Mecca” “Town Without Pity”) or even by the lovers’ own personal failings — “Twenty Four Hours from Tulsa” tells the story of a lovesick narrator on the way home to be with his “dearest darling,” but who gives into temptation, only one day’s drive away from her.

“Oh, I was only twenty four hours from Tulsa /

Ah, only one day away from your arms /

She took me to the café /

I asked her if she would stay /

She said, “Okay.”

Oh, I was only twenty four hours from Tulsa /

Ah, only one day away from your arms /

The jukebox started to play /

And night time turned into day.”

The narrator concludes by saying he can never go home again. The best term to sum up the theme of Pitney’s songs would be the title of his 1963 single “True Love Never Runs Smooth.” In Pitney’s world, something or someone is always standing in the way; sometimes even the lovers themselves.

While Pitney drew from the pre-Elvis crooners and pop balladeers, Dion DiMucci was a product of the street corners of New York City’s outer boroughs, and appropriately, took inspiration from the countless doo-wop groups that were beginning to peter out by the early 1960s. The former leader of doo-wop combo Dion & the Belmonts, DiMucci possessed the tough, swaggering voice of the streets whence he came, prefiguring Bruce Springsteen by a good 15 years.

The Belmonts, consisting of four young Italian-Americans from Belmont Street in The Bronx, represented one of the key steps in the transition of doo-wop music from an African-American cultural tradition to an Italian-American tradition. As black vocal groups like The Drifters and The Miracles drifted from doo-wop to what would be called “soul music,” Italian-American groups like The Capris, The Elegants, The Mystics, and Randy & the Rainbows picked up where their black predecessors left off, creating an unmistakable impression that doo-wop was in fact an “ethnic” music. Dion & the Belmonts, who broke through with the upbeat, irresistible hit “I Wonder Why,” either naively or provocatively played up this connection by repeating “Wop, wop, wop, wop, wop, wop, wop!” in the refrain of said hit song.

While some doo-wop singers, particularly the white ones, sounded almost catatonic when singing (there was even a one-hit wonder called The Monotones), Dion could not help but convey a great deal of pride and strength with his voice. Even in a song like DiMucci’s 1961 solo hit “Runaround Sue,” a superficially heartbroken tune about a young boy who falls for the eponymous Sue, not realizing that she “goes out with other guys,” DiMucci could not help but sound confident, even cocky. Perversely, this seems to work to the song’s benefit. While in another performer’s hands, the song might have come across as your typical weepy ballad, with DiMucci singing, the singer/speaker’s hubris in falling for the forbidden fruit comes across more strongly, leading to a more complex, layered song.

DiMucci’s confidence really came through on “The Wanderer,” the double standard flipside to “Runaround Sue,” where Dion boasts that:

“Oh, well, I’m the type of guy who will never settle down /

Where pretty girls are, well, you know that I’m around /

I kiss ’em and I love ’em ’cause to me they’re all the same /

I hug ’em and I squeeze ’em, they don’t even know my name.

They call me the wanderer /

Yeah, the wanderer /

I roam around, around, around, around.”

With its strutting rhythm and bold, brass saxophone perfectly complimenting Dion’s winning, ahead-of-its-time vocal performance, “The Wanderer” might be the definitive Dion song, though it’s in good company with “Ruby Baby,” “Lovers Who Wander,” and “Donna the Prima Donna.” Unfortunately, there were limits to DiMucci’s vocal style. While he could be the prideful swaggering young man, or the defiant spurned lover, to “play” a genuine loser was somewhat out of his grasp.

Compare, for instance, these three versions of the Roy Orbison-penned ballad “Crying.”

Great stuff.

A few years later, in 1967, Gene Pitney recorded his own version. It might be even better than Orbison’s take.

Here, for comparison, is Dion’s recording from 1961.

Patently, it’s just the wrong match of singer and material. DiMucci seems to be chafing at the challenge of presenting a man lost in real despair. This version, wisely, went unreleased.

Del Shannon was probably the purest rocker of this generation of singers. Shannon, a guitar-strumming working musician from Battle Creek, Michigan, launched himself to rock immortality with his debut single, the timeless “Runaway.” The song was an instant success, and went to the very top of the Billboard charts in the spring of 1961.

Opening with a chilling guitar riff that segues into the sound of the weird and innovative electric keyboard the Musitron (a forerunner of the synthesizer), “Runaway” tells a fairly boilerplate story of a boy whose girl ran away, but transcends the formula through its avant-garde instrumentation and Shannon’s killer performance of the lead vocals, perfectly transitioning from DiMucci-esque gritty swagger to Pitney-esque weepy falsetto.

If DiMucci was the bridge from doo-wop, and Pitney was the bridge from traditional pop, then Del Shannon was the bridge leading into the British Invasion. His more guitar-driven sound, and his predilection for minor chords and a strong backbeat, predated the game-changing acts that would be coming out of Liverpool, Manchester, and London in a few years. Notably, he was one of the first American artists to cover a Beatles song, knocking out a very close cover of “From Me to You” in 1963, making it, in fact, the first Lennon-McCartney composition to hit the American charts.

With songs like “Hat’s Off to Larry,” an oddly cruel ditty about a young man’s expression of joy upon hearing that his ex has been dumped by the eponymous Larry, “Two Kinds of Teardrops,” “Little Town Flirt,” and “Keep Searchin’ (We’ll Follow the Sun),” Shannon was the most ahead of his time, even if he could not maintain his success when his British counterparts successfully made the transatlantic journey.

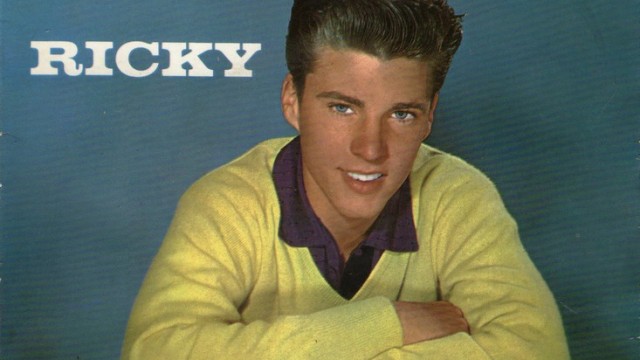

Of all the members of this class of performers, it might have been Ricky Nelson who was both the most artificial and the most real. Nelson was, on paper, the definition of the pre-fab pop star. Unlike Elvis, Nelson didn’t have the classic American artistic success story. He didn’t get to be a rock star by working his way up from the bottom, cutting his teeth on the live concert circuit, fighting his way to the top based on the combination of raw talent and work ethic. No, Ricky Nelson was show business royalty, to the soundstage born. He was the son of Ozzie and Harriet Nelson, popular big band performers who’d had their own radio sitcom since the early ’40s. His childhood must have been quite surreal, as the radio production of The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet purported to be a behind-the-music look at the home life of the Nelsons, with an actor playing “Ricky” until 1949, when the real Ricky took over the part. He was eight years old.

The success of the radio show led to an ABC TV sitcom in 1952. It was a hit that turned the preteen Ricky into a nationally beloved child star. Essentially, he was the Miley Cyrus of the Atomic Age. In 1957, the teenaged Ricky performed a cover of Fats Domino’s “I’m Walkin’ ” in an episode of the show. It was a decent cover. It lacked the soul of Domino’s original, but that was to be expected. This was rock ‘n’ roll for middle America, for Mom and Pop’s living room. Ricky was not Elvis. But he had something. Even in his short rendition of the song he displayed a great control of his voice and suggested a promising future as a performer.

For all the edges that seemed to be sanded off in his music, Nelson was always an important and powerful artist. He was the Rimbaud of ’50s pop. Found in his body of work was the alienated, almost film noir-esque psychology of a wounded and lonely young man who has seen his choices stripped away by an unfeeling world. Is that a bit of a melodramatic way of talking about high school flings? Probably. But it accurately represents something of the dark and genuinely depressive qualities of failed relationships of the young. It may have been high school noir, but damn if that’s not an interesting place for an noir.

The persona that Nelson adopted in his songs was that of a loner, a loser, a man who seems to have everything on the outside but is broken and hollow on the inside. His defining song is “Teen Age Idol” — released when Ricky was 22, but whatever — a song that sought to deconstruct the figure of the rock idol.

“Some people call me a teenage idol /

Some people say they envy me /

I guess they got no way of knowing /

How lonesome I can be.”

Nelson didn’t have the most powerful voice in the world; it was thin and his range was hardly operatic. But it had an appropriately melancholy quality, a vulnerability that only Orbison, the best singer of the bunch, could otherwise approach. He sounded the way Montgomery Clift looked, fragile and heartfelt, without being completely defeatist.He knew how to utilize the talents of guitarist James Burton, a prodigious guitar picker who gave Nelson’s songs their spine. He knew how to pick songs that perfectly suited his voice and his persona.

From 1957 to 1964 Nelson released a string of singles that I would put up against just about any of his contemporaries. Although not as well-remembered today as Presley or Orbison’s hits, Nelson’s hits included “Travelin’ Man,” “Poor Little Fool,” “Everlovin'” “Lonesome Town,” “Hello Mary Lou,” and many many more. The key theme running through Nelson’s songs was a kind of alienated resignation.

In 1960, Nelson sang

“You are the only one /

My one and only one /

Together we’ve had a lot of fun /

But what’ll I do if you leave me?”

Even when he was with the one he loved, Ricky could not feel the security that he wouldn’t be left alone at the end of the story. In his other songs, Nelson confessed that he had no control over his life or what would happen. The most reflective song titles are “There’s Nothing I Can Say” and “It’s Up to You,” the latter sung to a lover who holds the future of Ricky’s relationship with her in her hand.

“It’s up to you /

No, it’s not for me to say /

You love me too /

Oh, but I hope you feel that way.

Make up your mind /

And do what you’re gonna do /

Well you know how I feel /

So I’m leaving it up to you.”

For alleged teeny bopper mush music, Nelson’s body of work displays a quietly weary, bittersweet quality with the emphasis on the bitter. He could perform uptempo songs — “Hello Mary Lou” is a great rocker and “Fools Rush In” swings with a real verve — but his most representative tracks are those that show off Nelson’s status as the poet-prince of young male isolation. If one is willing to move the traditional goal posts of rock ‘n’ roll mythology, then they may even see a lineage connecting Ricky Nelson’s late ’50s/early ’60s singles with the groundbreaking work of Bob Dylan around the tail end of that time. In his autobiography, Dylan even admitted than he “always felt kin to him,” suggesting that the iconic “innovation” of Dylan’s early output was in fact a revitalization of Nelson’s music, placed alongside many other threads of music history and woven into a tapestry that felt brand new even when its material was old as the hills. But that may be a topic for another time.

And then it all stopped.

Well, not all at once. But pretty quickly. In 1964, The Beatles made their way across the Atlantic, causing as big of an impact on pop music as Elvis had almost a decade earlier. The princes of rock ‘n’ roll were on their way out, to make way for The Rolling Stones, The Who, The Byrds, and, yes, Bob Dylan. The melodramatic rock-pop of Orbison, Pitney, DiMucci, Shannon, and Nelson was not much longer for this world. There would be a few more hits for the pack, but their heat was fading.

Nelson’s records had begun to do better on the Adult Contemporary charts than in the Hot 100, possibly indicating the aging of his target audience, and in 1964 he released his last top 40 single for five years. He refocused on country music, and was able to maintain a more-or-less modest but steady level of success until his untimely death in 1985 at the age 45. Shannon recorded sporadically; he dabbled in production and had a few attempts at a comeback. He struggled with chemical addictions, and took his life in 1990 at the age of 55. Dion DiMucci made a series of career-hurting moves that seemed to nevertheless satisfy him creatively — he recorded blues tributes, Hendrix covers, contemporary Christian music. He didn’t have much commercial success with these, but his elegiac tribute ballad “Abraham, Martin, and John,” written in the aftermath of Robert Kennedy’s assassination, eulogized the murdered RFK along with his older brother, with Martin Luther King, and with Abraham Lincoln. It sounded nothing like his previous hits, but went to #4 in the summer of 1968 and was certified gold. It’s a little rote but its heart is in the right place, which I imagine you could also say about most of DiMucci’s stuff since then. He’s still around, still recording. Gene Pitney also moved away from rock ‘n’ roll, recording well-received country albums as well as Italian-language pop. He was a regular presence in the U.K., touring and releasing hits into the ’80s. He passed away in 2006. Roy Orbison, as a truly transcendent artist, could never really go away — but that didn’t mean he didn’t have long periods of the doldrums. In 1965, he starred in odd Elvis reject western The Fastest Guitar Alive, which flopped — you can probably skip the movie, but check out the song “Pistolero” from it, as the tune is pretty damn catchy. In the late ’80s the stars seemed to align for a brief moment, and Orbison became not just a hitmaker but something of a pop culture sensation. His reemergence coincided perfectly with the ascent of director David Lynch, who unforgettably used “In Dreams” in his 1986 film Blue Velvet. Orbison’s persona and songwriting mystique, far too strange for the Eisenhower era, fit perfectly in Lynch’s bizarre yet beautiful world of ’50s melodrama gone haywire, with the dark impulses of idol-era teen culture amplified and exploded to metaphysical heights. Orbison scored a final smash hit with 1989’s “You Got It,” not long after his death at the age of 52.

What is there to learn from this short-lived generation of post-Elvis singers? It’s true that most of them were not provocative or especially shocking. They were cleaned up from the raunchy older styles, cleaned up to save the rock world and sell it to middle America with a nice sweater. But that missing raunchiness shouldn’t be the only quality praised in rock music. In fact, it might be better to say that this style was music of the rock ‘n’ roll era without necessarily being rock ‘n’ roll. Whatever it was, in this style I hear Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby, but also Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen. I hear Hank Williams in a honky-tonk in Alabama, but also countless black vocal groups on the streets of Harlem. There’s a bridge in this music, linking disparate styles and sounds and strands into a whole that was a much needed and organic part of the evolution of an art form. Found within the works of Roy Orbison, Ricky Nelson, Dion DiMucci, Del Shannon, and Gene Pitney is the bleeding heart of the youthful angst that was yet untouched by the tumult of the latter half of the ’60s. It’s a deeply personal angst, owing not to politics, not war, not riots, not assassinations, but simply to that most innately human of troubles — the nature of love and of love lost. It derives from an introspection owing not to psychedelic drugs but to long, lonely nights spent driving on the road from Battle Creek, Michigan to sunny, cold, beautiful, terrible California. It’s youthful and jaded and painful and jubilant and it’s heaven and it’s heartache.

Perhaps I’m being melodramatic.

But wouldn’t that be just about right?