Due to its subject matter, Gimme Shelter resides as a cultural landmark between Woodstock: 3 Days of Music and Peace and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Gimme Shelter began its life as a Rolling Stone tour documentary, and ended its life documenting the notorious Altamont Free Festival, and being known as the Rock n Roll Zapruder Film.

Criterion released Gimme Shelter in both a DVD and a blu-ray edition, both containing a booklet of essays discussing the cultural impact of both Gimme Shelter and Altamont (though the reissued booklet is missing an incredibly important essay from Sonny Bolger). In the 41-page booklet, the essayists start piecing together the disparate elements that make Gimme Shelter an important film. 3/4 of these are all in the incidents depicted on screen, and another 1/4 are in the filmmaking process itself. In order to truly understand Gimme Shelter, one must go back in time to the four-hour Woodstock documentary.

Woodstock, porta-potties, and hamburger stands

I watched Woodstock: The Director’s Cut for the first time recently. I had seen bits and pieces of it before, but Woodstock taken as a whole is daunting enough without the Director’s Cut making the movie seem taxingly long and self-indulgent. Just like the festival itself. For all the great elements that are within Woodstock, the most important piece of film is 3 minutes hanging out at a port-a-potty with a cleaner, who was dubbed the Port-o-San man.

Well into the film, just before Jimi Hendrix’s Monday Morning segment, the documentarians insert three minutes of footage featuring Thomas Taggert, Jr, a man who was hired to clean up the porta-potties that were meant to contain the waste of the millions of hippies who were partying to protest the war. Mr. Taggert cheerily cleans up the toilet, locks down the toilet paper so that it doesn’t fly off the handle, and uses deodorant to make the place just a little bit better for the hippies. Before long, Mr. Taggert reveals that he has a son there at Woodstock, and another son in Vietnam. He seems to love both equally, and is dealing the best he can to make everything a little better.

After this bomb of a reveal, he saunters off. Soon after, a stoned and clueless hippy comes out, takes a toke on his pipe and believes the camera crew when they say they’re making a documentary called Port-O-San. This is the type of person we’re talking about. A stoned and self-centered person who only believes that the porta-potties are better than shitting in the woods.

Just before this landmark scene, Wavy Gravy makes the announcement, “There’s a guy up there—some hamburger guy—that had his stand burned down last night. But he’s still got a little stuff left, and for you people that still believe capitalism isn’t that weird, you might help him out and buy a couple hamburgers.” The story behind this announcement underlines all that will happen during Gimme Shelter.

Prior to Woodstock, and not included in the documentary, the organizers had arranged to have Nathan’s Hot Dogs from Coney Island at their food vendors to feed the concert attendees. But, just prior to the event the Nathan’s Hot Dogs guy and a Woodstock organizer got into a fist fight over staffing and economics. So, Woodstock ended up hiring some newbies called Food For Love to handle the concessions.

However, Food For Love was so green, the food stands were barely finished by the time of the concert. Just to add to Food For Love’s unprepared state, the Woodstock organizers had vastly underestimated the attendance of the concert. Even in the course of the movie, the attendence is vastly underestimated to the eventual final number. Of course, the hippies didn’t bring their own food and swamped the stand. Food For Love began running out of food, and jacked the prices up to try to stem the flow. For example, a hot dog, at the time, was going for $0.25, and they had jacked up their prices to $1.00 (a 400% markup). The Woodstock attendees became angry at the prices, and burned two of the stands down. As a side note, if you’re not seeing the origins of the debacle around Woodstock ’99, you’re not paying attention.

These attendees are the people we’re dealing with by the time we get to Altamont. These hippies, who are claiming to be full of peace and love, and fighting against war but are more than willing to burn down concession stands at the free concert they’re attending because they’re being jacked by the prices, are the ones who will be at the center of Gimme Shelter.

Gimme Shelter: The Culture: rock n roll, bad vibes, and culture clashes

Gimme Shelter: The Culture: rock n roll, bad vibes, and culture clashes

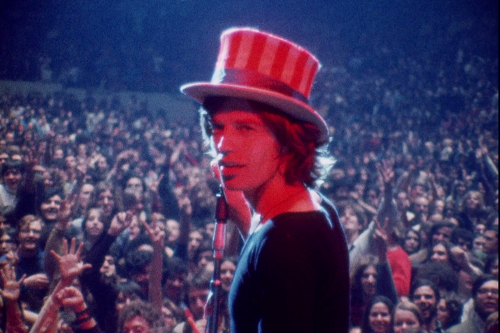

In come The Rolling Stones (and also Jefferson Airplane and Grateful Dead). Prior to the start of the film, and even before Woodstock, The Rolling Stones had put on a free concert in July in Britain that went off without a hitch, but that’s out of the scope of Gimme Shelter. Gimme Shelter opens with the Rolling Stones playing at Madison Square Gardens, and for the first half of the movie documents the American tour and recording sessions. Ike and Tina Turner were opening for them, and even have a number in the movie. The tour goes swimmingly, and the Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin capture and edit together some great footage of the concerts.

They also capture the behind the scenes of the Altamont Free Festival. This final free festival was originally supposed to be at the Golden Gate Park, and then at Sears Point. Finally, in the last few days, the location became the Altamont Speedway. The festival was planned in a matter of a couple of months at most. By contrast, Woodstock took 9 months to organize. We see lawyers fighting over publicity, and the bad vibes left behind by the destruction Woodstock left in its wake. The owner of Altamont Speedway comments that he doesn’t want to have to pay for any damage to his land, as he had seen the Woodstock wreckage resembling a wasteland of mud, garbage, and various other detritus left behind by the freeloaders. News reports were saying that the Rolling Stones were desiring to create a Woodstock West. And, in one of the most darkly hilarious moments, the owner of the Speedway said that he wanted to make sure that Altamont Speedway got publicity for the event.

Mind you, the Altamont Free Festival wasn’t solely the work of The Rolling Stones. The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, and The Rolling Stones each had a part in brainstorming the idea for a free one-day music festival. In December. Outdoors. In San Francisco. One of the biggest problems to the movie Gimme Shelter is that it skates by this little note of who helped organize it. Zwerin and Maysles choose not to use name titles for any of the characters, so you have to kind of know who people are.

Somehow, stage security for the festival is left to the Hell’s Angels. Who arranged for the Hell’s Angels to be the security is not on the film, but the commentary on the Criterion comments that it was largely the role of Stones’ manager Sam Cutler who had arranged it with the help of Grateful Dead manager Rock Scully. Sam Cutler had worked with Britain’s Hell’s Angels during the Stones’ Hyde Park free concert. But, everybody acknowledges that the Brit’s Hell’s Angels and the US’s Hell’s Angels are different beasts entirely. Both the commentary track and the bonus feature radio show state that there was a large meeting of the chapter heads of the Angels during Altamont. Which means that the ones who showed up early were essentially pledges looking to prove themselves worthy of being Hell’s Angels.

Also wrapped into the commentary track are statements that the Hell’s Angels were commonly used as mild forms of security during free shows at Golden Gate Park. They were normally just to protect the stage from the people and prevent things from being damaged or stolen, and the like. It should also be noted that the Hell’s Angels were chaos elements who actually had a running reputation with both Ken Kesey and the Grateful Dead. In any case, it was the Angels who had been hired, and the Angels were noted upholders of conservative values.

Prior to any of this, there was a notorious party between the Hell’s Angels and the Merry Pranksters where they met over some LSD. No deaths happened at the party, but there was a gang rape/orgy (depending on whose version you believe) of a girl in the middle of the floor. That this party was held mere months after the Hell’s Angels went aggro on the Vietnam Day Committee’s anti-war protest is starting to tell where things were with the Angels. By the time of Altamont, the Hell’s Angels were, at best, tolerant of the hippies.

This festival would be different than the Hell’s Angels-aided concerts at Golden Gate Park. Due to the change in venue, the stage was abnormally low to the ground, at the bottom of the hill, and subject to being bum rushed. The Angels were meant to keep people off the stage and equipment, but people kept rushing the stage. In the film, the cameras catch the hippies crushing the people toward the front of the stage, climbing the speakers, and getting on stage. In the radio show feature, which was recorded the day after the festival, one of the callers commented that the crowd’s vibes were much more rabid than at Woodstock. There was a sense that you had to get all of Woodstock’s drug-fueled fun done in one day instead of being spread over 3 days and nights. The community feeling of Woodstock had been decimated by human’s inherent selfishness.

So, now we have aggro hippies and aggro Angels. During one of the scuffles, the Angels even knocked the lead singer of Jefferson Airplane unconscious with a punch to the head, leading to a situation where the Dead refused to play the festival. There’s another part where there’s a topless drug-addled girl in the movie who’s trying to climb up on stage. Hell’s Angels Oakland founder Sonny Barger relates the story as 5 Angels were trying to handle the situation without injuring her, but she wasn’t having it. Barger claims that Jagger then tells Barger that surely it doesn’t take five people to handle one girl, so Barger goes over and kicks her in the head.

The emotional climax of Gimme Shelter happens when, after Under My Thumb, a scuffle happens Stage Left, which results in an Angel stabbing a black guy. The first time it plays, you see the scuffle then see the knife as the Angel runs through it. The camera catches the guy on a gurney being wheeled to an ambulance helicopter with his white girlfriend crying and saying she has to go with him. The Stones finish the concert, flee the scene, and leave in their own helipcopter, leaving the rest of the people to make their way home. The commentary track notes that beatings continued through the night.

Gimme Shelter uses a framing device of showing Mick Jagger a cut of the footage they shot for the film, and the elements they have to build the film. Gimme Shelter closes by showing us Mick Jagger watching the footage. Jagger wants to be shown the knife specifically. Later, Jagger wants the footage rewound back rewound back to note the gun that the black guy was holding. Or at least the shape of a gun, as the camera is kind of far from the guy. We watch Jagger as he ponders the meaning of the gun. Was the murder a defense of Jagger? Could the guy have fired the gun and shot him? Shot an Angel? Shot an innocent concert goer? Then, he gets up, visibly disturbed, and says “Alright. See y’all.” The camera freezes on him leaving the studio.

Grace Slick, in the film, summed it up (pre-murder), thusly. “You don’t hassle with anybody in particular. You gotta keep your bodies off each other unless you intend love. People get weird, and you need people like the Angels to keep people in line. But the Angels also – you know, you don’t bust people in the head for nothing. So both sides are fucking up temporarily; let’s not keep FUCKING UP!” It’s obvious she was trying to placate the Angels a bit, even though she actually sided with the hippies. That intention makes the quote ring true for both Altamont and the culture as a whole.

Gimme Shelter: The Film: Capturing the intangible

Gimme Shelter: The Film: Capturing the intangible

So far, this whole thing is like a cultural book report. What about the movie itself?

Gimme Shelter bends the form of the documentary onto itself creating a film that looks at itself, reflecting the navel gazing nature of the content. The film opens with the Rolling Stones playing Jumpin Jack Flash at Madison Square Garden, reflecting the innocence of the time. If you didn’t know any of the above had happened, you’d think this was a traditional concert film.

Once the song ends, we bounce out to the editing room to watch Mick Jagger watch the footage. He watches himself in the Rainbow Room give rather flippant or shallow answers amid the chaos that comes with press kits. He cringes because the interview was given on December 3rd, a couple days before Altamont, before he knew what a disaster the festival would be. Then, they make Jagger listen to Sonny Barger on a phone call to KSAN radio, saying that, while the Angels were a violent element, that it was all the fault of the outrageously drugged out hippies and the egomaniacal Rolling Stones and Mick Jagger.

Instead of making this a purely Altamont documentary, the Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin make this into a documentary about everything around it. They spend half the movie following the Stones preceding the festival. One particularly masterful sequence happens at Muscle Shoals Recording Studio. The Stones listen to a new recording of Wild Horses in one of the finest filmed sequences (and long takes takes) in documentary history. The Maysles manage to capture the pondering of the recording, the contemplation of the lyrics and sound, all without talking. It’s a music video within the movie for one of the Rolling Stones’ best songs in their history. It also belies the events that were to come after.

The Maysles and Zwerin intercut footage of Ike and Tina Turner as the opening act with I’ve Been Loving You Too Long. And, they also fill in the one-sided documentary footage of the setups with the producers and Melvin Belli as they arrange to get Altamont Speedway for the new location. This is what the audience was clamoring for. Who was responsible, and why?

The Altamont section is free from interjection until the murder. The footage they captured is an attempt to catch the happy-go-lucky vibes they hoped the Festival would be. The Maysles supposedly told their cameramen to film the positive and avoid the negative. But, slowly, the bad vibes creep into the footage. They were attempting to recreate a Woodstock style concert film, and instead managed to capture a descent into animals of all sides.

Gimme Shelter passes no judgement by using the techniques it does. It suggests that the Rolling Stones were culpable for the behavior because they were the primary organizers. It suggests that the Hippies were culpable for being stoned off their ass, and were also being increasingly violent. It suggests that the Hell’s Angels were also out of control, capturing their beatings with pool cues that had weights attached to them.

The Altamont section is a class study in changing the intent of the documentary on the fly. Watching the footage devolve, via editing as well as filming, from excitement to sorrow to anger, Gimme Shelter becomes a self-reflexive master class on how to shoot documentaries. That is, being true to what is around you instead of trying to force a perspective.

Because of the layered editing, The Maysles and Zwerin try to draw the lines, even if they can’t capture all of the details. They missed Barger’s claim that the hippies were shorting out their bikes by knocking them into each other. They missed the post-concert beatings. They didn’t include any of the security arrangements with the Hell’s Angels. These were incidental. They also all but omitted the Grateful Dead, who make a cameo appearance emerging from a helicopter. Though, the film doesn’t note that they completely skipped the festival, leaving a multi-hour block of boredom where the Stones weren’t ready to go on, and nobody else was on stage, leaving the audience waiting in silence in the cold.

Still, these details pale in comparison to watching Jagger process the murder on the screen. If you didn’t know anything about the social context surrounding Altamont, this would be just watching the destruction of a festival due to forces outside your understanding.

Which brings up an interesting comment about the intrigue of Gimme Shelter. Gimme Shelter wasn’t made as a book essay on the culture. All the stuff in the first half of this essay? Most of that is knowledge picked up, researched, or included as bonuses from the Criterion release. Without it, Gimme Shelter might exist in a vacuum. The Maysles and Zwerin do not bother to stop to explain the nature of the Hell’s Angels, nor the hippy culture, nor the importance of a free festival. The audience of the time knew most of this, and didn’t need it repeated or explained for them. I wonder if Gimme Shelter could hold the same power without the cultural knowledge that Altamont represented the death knell of the 1960s.

The Aftermath: Fear and Loathing in Counter-Cultural America

The Aftermath: Fear and Loathing in Counter-Cultural America

The two songs that The Stones were playing before the murder were Sympathy for the Devil and Under My Thumb. The first song mentioned by title in Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is Sympathy for the Devil, which Dr. Gonzo (up until then referred to only as “my attorney”) is playing on a tape recorder at full volume to contrast with the radio. The radio was playing Brewer and Shipley’s One Toke Over the Line, which landed them on Nixon’s Enemies list and was also featured on Lawrence Welk. The contrast of these elements, all mentioned within the first few pages of the novel, are indicative of the cultural war at the center of Thompson’s manifesto.

Later in the novel, Sympathy for the Devil gets name checked again in a chapter title. In the novel, Thompson writes the “Strange Memories on this nervous night” speech about the idealism of the 60s, and the next chapter is titled “No Sympathy for the Devil,” showing how the idealism turns on the flip of a switch.

Altamont itself gets name checked in the novel following the “Light at the End of the Tunnel” section. In the “Strange Memories” speech, HST was remembering the beginning and the idealism of the counter-culture. In this second section, he’s detailing the harsh realities of the end. Forgive me for recreating a large section here, but I feel it’s important to understanding everything about the cultural undercurrents in Gimme Shelter.

Sonny Barger never quite got the hang of it, but he’ll never know how close he was to a king-hell breakthrough. The Angels blew it in 1965, at the Oakland-Berkeley line, when they acted on Barger’s hardhat, con-boss instincts and attacked the front ranks of an anti-war march. This proved to be an historic schism in the then Rising Tide of the Youth Movement of the Sixties. It was the first open break between the Greasers and the Longhairs, and the importance of that break can be read in the history of SDS [Students for a Democratic Society], which eventually destroyed itself in the doomed effort to reconcile the interests of the lower/working class biker/dropout types and the upper/middle, Berkeley/student activists.

Nobody involved in that scene, at the time, could possibly have foreseen the Implications of the Ginsberg/Kesey failure to persuade the Hell’s Angels to join the radical Left from Berkeley. The final split came at Altamont, four years later, but by that time it had long been clear to everybody except a handful of rock industry dopers and the national press. The orgy of violence at Altamont merely dramatized the problem. The realities were already fixed; the illness was understood to be terminal, and the energies of The Movement were long since aggressively dissipated by the rush to self-preservation.

Thompson had, in a separate book, earlier written about the Hell’s Angels, and it’s clear he didn’t understand what their trip was. Or, he understood it, he just rejected it. He said, at one point, that the Angels were supporting a culture that, when it gained power, would turn around and lock them up. HST obviously blamed them for the schism they helped create, believing in the power of the freak.

But, Thompson represented the cynical side of the energies. He has the right thought that the energies of The Movement moved toward self-preservation. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that The Source Family is getting publicity lately. The Source Family is the sensible side to hippy hedonism, with rules like “Don’t stay baked all day” and “eat natural food” and “respect your body.” They’re based in sensibility, and could provide a reasonable set of guidelines to the next wave of radicals.

But, Thompson represented the cynical side of the energies. He has the right thought that the energies of The Movement moved toward self-preservation. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that The Source Family is getting publicity lately. The Source Family is the sensible side to hippy hedonism, with rules like “Don’t stay baked all day” and “eat natural food” and “respect your body.” They’re based in sensibility, and could provide a reasonable set of guidelines to the next wave of radicals.

I say this because the radical energies and the anger of the 60s are popping back up among the Millennials. While it seems shallow to say that the dual nature of Woodstock and Gimme Shelter provide a guide for what came before, if you read between the music then these two documentaries point out guidelines for making something work and for avoiding the pitfalls a movement can fall into.

This is why Gimme Shelter is most important. It judges everybody, yet doesn’t come down to a conclusion. Instead, Gimme Shelter informs the energies that came to a head in 1969. It chronicles how the flaws of a culture destroyed a movement that was running counter to the government’s war mongering conservatism that was also calling upon the Southern Strategy to express fear of the black culture. Meanwhile, in Gimme Shelter, the Hell’s Angels killed a Black Man who had a gun.

Nixon took office in January of 1969. The Youth Movement’s death was dramatized in December of 1969.

Pay attention. This was important.

Final note: Criterion’s website notes that Sonny Barger’s excerpt is only in the DVD booklet. This excerpt is, instead, on their page for Gimme Shelter. It’s a must read.

This essay was originally intended for Let’s Dissolve the Criterion. Posted with permission by that organizer.