A few years ago, while in Paris, I went on a pilgrimage to find a building that doesn’t exist: 11 rue Simon-Crubellier. Its purported location was a sleepy neighborhood in the city’s 17th arrondissement, on an imaginary street that cuts through the block created by rue de Chazelles, Léon Jost, Médéric, and Jadin — the same block, incidentally, where the Statue of Liberty was conceived and designed. I knew the building wasn’t there, but having lived inside it mentally for so long, I wanted to know what the neighborhood was like, to add the sounds and smells of streets to my mental inventory, something to access every time I return to the world of Georges Perec.

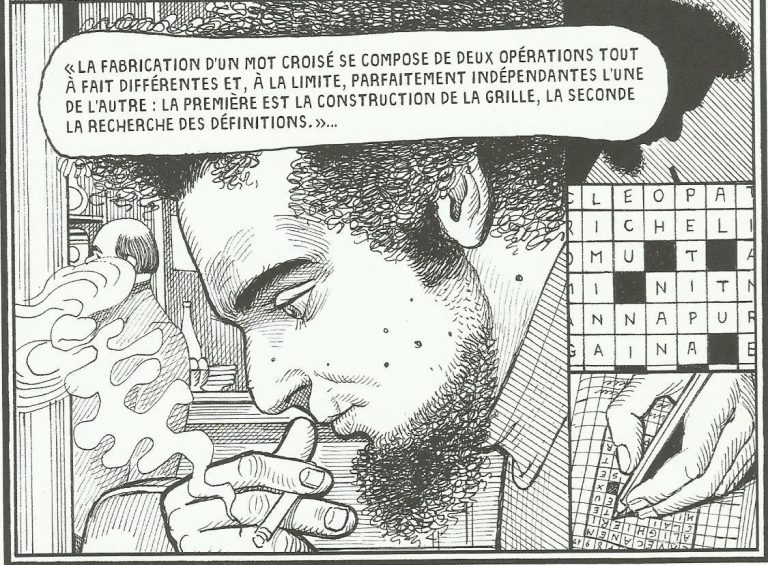

Life a User’s Manual is my favorite book, and I already had some premonition that it might be the first time I reached the end of the preamble. Perec opens his set of “novels” (the book’s subtitle) with a short and informative discourse on puzzles – how they’re made, the official names of various types of pieces (with diagrams for reference), etc. – and he wraps up with an observation that suddenly grabs you, the reader, by the collar:

From this we deduce something that is without doubt the ultimate truth of the puzzle: despite its appearances, it is not a solitary game: each gesture that the person completing the puzzle makes, the puzzlemaker has made before him; each piece that he chooses and re-chooses, that he examines, that he caresses, each combination that he tries and tries again, each blunder, each intuition, each hope, each discouragement, have already been decided, calculated, and studied by the other.

Here we are, on the threshold of a heavy (over 600-page) tome, and the author is already warning us: do not think that you are here alone. Life is a puzzle, we are its players, and someone outside the book has already calculated – in fact, is counting on – us to play it a certain way. Even its choice of an epigraph, from Jules Verne’s Michel Strogoff, is a warning: “Look, and look carefully!” (Better in French: “de tous tes yeux” – “with all your eyes”)

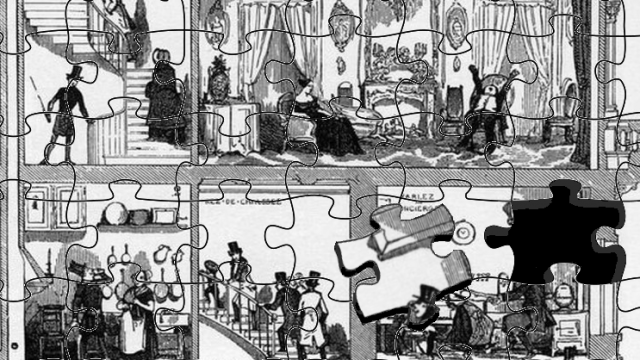

For the next ninety-nine chapters (plus epilogue, plus over 60 pages of appendices), we will explore a single building, that ten-story apartment complex at 11 rue Simon-Crubellier, and we will be exploring it at a single moment in time: just before the clock strikes eight p.m. on June 29th, 1975. Why this moment? As Perec tells us at the end of chapter one,

Gaspard Winckler is dead, but the long vengeance that he so patiently, so meticulously contrived has not yet been fulfilled.

What a hook, right? Winckler’s revenge is only one of the many, many crisscrossing plots that make up the material of Life, one of those massive tapestries of modern literature that eschews the focused narrative centers of the 19th century novel in favor of a labyrinth of digressions, shifts in style and tone, and generic play. The book serves us eccentric millionaires and starving artists, fancy dining rooms and cramped attic apartments, peculiar hobbyists and religious cults, complex math equations, chessboards, crossword puzzles, cryptograms, recipes, nursery rhymes, history and philosophy, affairs and intrigues, young and old, French and immigrant, living and dead. Some of the stories are tragic, some are hilarious – some are actually nonfiction, and others shamelessly stolen from other writers and reworked, with a tongue-in-cheek note in the appendix listing the sources of his thefts. The result is overwhelming, and when you finish reading, as Catherine David said in her review, “you feel as light as a hot-air balloon.”

The narrative structure, on the other hand, is (deceptively) simple: each chapter represents one room in the building. In most cases, Perec merely tells us what’s inside – and maybe a postcard on the dresser leads to a story about how the resident came to live there, or a dusty painting prompts a discussion of the previous tenants, or even a history of a particular table elicits its own self-sufficient story. Maybe the room is occupied and we see the actors frozen in a moment of conversation. Maybe the room is empty and we learn why no one lives there anymore. Each room – each piece in the puzzle – fills in the overall picture a little more completely, plot threads start to cohere, the lives of characters intertwine, until finally… Well, what if the last piece doesn’t fit, after all?

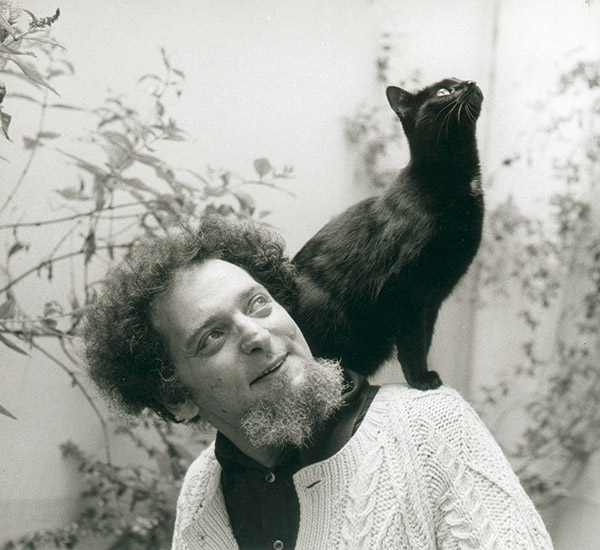

There’s a deep vein of melancholy in this and all his books, and it helps to know a little about Perec himself. His early life was nightmarish: he lost his father in fighting against the Nazi invasion of France and his mother to the extermination camp in Auschwitz. He was passed around through a network of family and friends to keep him, a young Jew, hidden and safe during the occupation. He survived, but what he remembers of his childhood, he tells us in his memoirs, is fragmentary and misleading.

It’s easy to imagine a morbid artist emerging from this, but even though that sense of loss cuts through all his work, Perec somehow transformed into a playful and amiable voice, greatly loved by readers and critics, friends and colleagues. For years, he designed crossword puzzles for Le Point. He was an award-winning filmmaker. He engaged in silly feats of language, earning a place in the Guinness Book of World Records for longest palindrome. While working as a science archivist, he submitted a satirical research article about throwing rotten fruit at opera singers, “Experimental demonstration of the tomatotopic organization in the Soprano (Cantatrix sopranica L.)“: allegedly, the review board had to adjourn from laughter.

Just because it’s fun doesn’t mean it’s empty. His breakthrough novel Things, for example, is an uncompromising satire on the way consumer capitalism fills us with false promises of happiness then grinds us into dust. Like the apartments in Life, Things earns its verisimilitude from a detailed materialism that uses objects as stand-ins for direct psychological description. In the wrong hands, this could be tedious list-making, and often was in the novels of Perec’s nouveau roman predecessors, but Things became a literary sensation because of the electric jolt of Perec’s wit and specificity. It’s a tremendous book: funny and sad, and it cuts to the bone.

Two years after Things, Perec joined Oulipo, a group of writers, mathematicians, and other artists who experimented with the idea of Constraint in literary form. One of its founders, the great humorist Raymond Queneau, had become disillusioned with the way Surrealism preached freedom but seemed to circle the same drains. By pointedly limiting our freedom, however, we are forced to choose new and different avenues of expression. Writers like Italo Calvino and Harry Mathews would do some of their best work as members of Oulipo.

Perec the puzzlemaker was delighted by the concept and became one of the group’s most ambitious members. The Oulipean influence is most direct in his most (in)famous work, the lipogramatic novel La dispiration (translated as A Void or Vanish’d) which, apart from the author’s name, contains no uses of the letter E. The story follows a detective searching for a missing person, then persons, as others characters vanish around him — a book whose reputation for frivolity belies the actual content, where the surface humor allows us to smile through the despair. Among other things, Perec is working through the disappearance of his mother (her death at Auschwitz was never confirmed: he received a certificate of “dispiration” acknowledging she had been sent there), the kind of world in which people vanish and, with apologies to Proust, time cannot be re-found.

Because of his association with Oulipo and the nature of some of his works, he has many (many) detractors, including some contemporary critics who treat his process with a kind of snooty condescension. That kind of reputation can be damning and prevent new readers from approaching him at all: the halo of allegedly frivolous formalism was so strong that Glenn Kenny says he practically had to force David Foster Wallace to give Perec a chance (Wallace became a fan, natch.) But the cult of Perec persists for three reasons: 1) the “gimmicks” are always meaningful and deeply integrated into the work’s reason for being, 2) his work has enormous depth, with increasingly relevance in the 21st century, and perhaps most importantly 3) readers typically find him to be such a warm, generous, and charming presence. Perec may not be the kind of writer you want to be, but he’s almost certainly the kind of writer you want to be around.

He also avoids many of the traps that plagued contemporaries in Europe and the United States. Like the writers Wallace labeled “Great Male Narcissists,” Perec spends a lot of time mining his own self for material, but the results couldn’t be more different:

Taken as a whole, Perec’s writings are densely and obliquely self-referential. He is immensely protective of his own early ideas. This suggests an egotistical man, but Perec was profoundly and instinctively modest, and by far the strangest and most moving thing about his work is the way in which it records an obsession with himself, his history and his own literary productions that is devoid of any selfishness or egotism.

A lot of this is due, I think, to that generosity of spirit. Perec’s works are deeply layered adventures, and his authorial voice reads as a congenial fellow traveler. He is delighted by discovery. He takes joy in the flexibility of his tools. Even in the face of despair — and we will encounter despair in his works — he wants to share that possibility of joy with us.

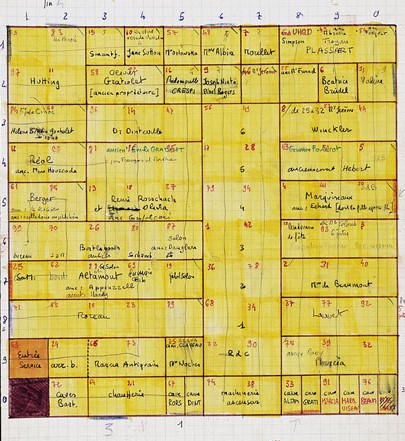

All that said, Perec did regret publishing the “scaffolding” behind the book — like Joyce’s framework for Ulysses, it can become an interpretive crutch rather than an enrichment. Still, it’s almost impossible to avoid mentioning this, at least broadly. The building at 11 rue Simon-Crubellier is designed like a 10 x 10 chessboard, and the order of chapters proceeds by the Knight’s Tour – that is, each chapter’s location will be the knight’s “L”-shape distance from the previous (click here to watch it in action). To generate material for the book, Perec outlined a massive series of constraints distributed via a Graeco-Latin square. He also gave himself permission to ignore them whenever inspiration took him elsewhere. Readers can ignore them, too.

Life swirls like a whirlwind of unrelated data, but as we jump from room to room, a few threads start to emerge. Bartlebooth, a cynical millionaire, wants to blow his money on a pointedly useless art project. Winckler is the craftsman Bartlebooth recruits for his skills as a puzzlemaker. Valène is the painter paid to train Bartlebooth in watercolors, but he’s also engaged in his own project: a detailed painting of the very building he’s inside, including all the residents we’re reading about (i.e. he is painting the book Perec is writing). Other characters are either tangentially or entirely unrelated to this central trio, from the young couple running a high-profile music agency out of their apartment to the eccentric “word-killer” hired to expunge archaic words from dictionaries. Some of the residents live in luxury, others in squalor. “Some are gone, and others distant,” to quote Alexander Pushkin, who makes an appearance in Chapter 67. The residents’ stories crisscross continents, centuries, class and ethnic borders. Different as they may be, all these lives collide in the stairwell, the one piece of shared space in the building. The elevator is always broken.

At times it seems like Perec is trying to write the whole world. A few years before, he’d spent three days at Place Saint-Sulpice scribbling down everything he could see and hear, which he published as An Attempt at Exhausting a Location in Paris. He notes with dry humor that his experiment is a necessary failure: the very act of focusing on things to describe means he misses other things happening around him. Space will always resist exhaustion. He revisits this concept in Life with an added twist: now he’s limited himself to a single time, as well.

Life is no more successful, because time is every bit as slippery, if not more. Time makes a mockery of our plans, and once lost, it can never be regained. Perec’s plan (and Bartelbooth’s, and Valène’s) fails because it must fail, but failure and forgetting aren’t the end of the story. Here, describing Valène’s painting in Chapter 51, the author Perec peeks briefly from behind the curtain:

He himself would be in the painting, in the manner of those Renaissance painters who reserved for themselves a minuscule place among a crowd of vassals, soldiers, bishops, or merchants; not a central place, not a privileged or significant place at some chosen intersection, along a particular axis, according to some illuminated perspective or another, in the line of some deeply meaningful viewpoint from which a complete reinterpretation of the painting might be constructed, but an apparently inoffensive place, as if it had been done that way in passing, by chance, because the idea had come to him without knowing why, as if he had not wanted us to draw too much attention to it, as if it were just a signature for the initiated, something like a mark that the person commissioning the painting only tolerated as the painter’s way of signing the work, something only certain people would recognize before it was then forgotten…

But not forgotten completely: as Perec continues, those who know about the hidden reference in the painting will pass it on, generation to generation, art studio to art studio, and then, maybe, after enough time has passed, the truth can be reconstructed at last. Life a User’s Manual shows us the void that swallows all our plans, best laid or not, and ends with a overwhelming vision of impotence and failure. But if you look closely, with all your eyes, you’ll see a grin and a devilish little wink: Perec is waving to us from the page, and maybe things won’t be so bad after all.