We begin with TV-blurred, static-laced images: something mechanical, a circus, some kind of animal, a man walking, then we go into an excerpt from an old black-and-white movie serial (Darkest Africa, which is about as White Savior-ish as you’d expect from the title). It’s strange and somehow compelling, not the least because it immediately raises the questions what am I seeing? and why am I seeing this? What’s unique and challenging about Errol Morris’ Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control–easily my favorite documentary–is that by the end of the film, we will have answers to these questions, but Morris will have raised so many more. In Glenn Gould’s phrase, Morris is never “concerned that clarity could be the enemy of mystery.”

On the surface, this film is about four men and their work: wild animal trainer (more colloquially, lion tamer) Dave Hoover; topiary gardener Dave Mendonça; specialist in “naked mole rats” (who resemble nothing so much as a Giger’s chestburster from Alien) Ray Mendez; and MIT robot scientist Rodney Brooks. They talk about their work with the straight-ahead, looking-into-the-camera style that Morris made possible with his “Interrotron” camera, and Morris cuts their interviews together with scenes of them working, what they work on, and also a lot of other things that don’t make surface sense, usually circuses and old movies. (There are more elephants here than one would expect.)

Robert Richardson took over cinematography on this film, bringing the same kind of multiple lenses/stocks/angles/effects/speeds technique he used for Oliver Stone on JFK and Natural Born Killers. The results are different. Whatever else can be said about JFK, Stone created some compelling montages by binding the imagery that Richardson provided to the monologues of the characters. On its own terms (which, to be absolutely clear, are not the terms of facts or history), JFK built strong, coherent arguments. Natural Born Killers went for more chaotic, poetic montages, and didn’t really succeed; without the through-line of the monologues, Stone lost his way and created a lot of fast-moving, bloody pictures but nothing that made sense. Natural Born Killers illustrates the principle that not following the rules requires you to discover another set of deeper rules and work with them. I certainly paid attention while watching it and forgot the whole thing before I left the parking lot.

Morris has the advantage of being a much smarter and more controlled director than Stone, and that led him and Richardson to craft something much more enduring in Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control. The editing is less hyperactive than in Stone’s films, with Morris giving us time to think about what we see rather than use it for sensation. He uses the same technique of placing monologues under the imagery, but much of the time what’s being said doesn’t correspond directly to what’s being seen: images from one subject’s story appear while we hear another subject. This solves one classic problem in documentaries: what do you show while someone is talking? All four subjects here have distinct, interesting faces, but still, static shots of faces get old quickly and Morris avoids that. In addition, the disjunct between who speaks and what’s seen creates a benefit that’s essential to this film, encouraging links between the subjects and images, suggesting without ever definitively answering that there’s something going on here that links two or maybe all four stories, hearing about robots while seeing lions and realizing that he might just as well be talking about lions. (For this reason, even though their voices and presences are completely distinctive, I’m not going to identify any of the speakers here.)

Morris works edits as well as Kubrick. Here, it’s done to same effect as the voiceovers, to make connections between stories. He’ll cut from a discussion of consciousness as a way for God to “interface” with humans to how peanut machines affect lions, or from the living, walking animals of the circus to the stationary (from our perspective) animals of a topiary garden, keeping with the theme of different orders of beings interacting, jumping between themes and characters the same way Kubrick jumped across settings and epochs. (Edits can be a way to create continuities as much as to break them. This is a never not awesome aspect of cinema.) Like so much in the film, it’s implied rather than stated outright, and implied through the means of film, not words.

He shows a lot more than the facts; The Thin Blue Line, with its obsessive re-enactments, is an invisible cornerstone of modern culture–so many “cold case” TV shows take their film grammar directly from it. One element of Morris’ style that serves Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control well is the way he ends sequences. The last image in a Morris sequence often happens without any narration, usually only music or sound. Usually, that last image doesn’t summarize or explain but looks out of place, and Morris cuts in the middle of it to black and stays with that blank screen for a few seconds. (In The Thin Blue Line, that cut was often punctuated with a gunshot.) The pause creates a moment for us to think, to keep the questioning raised by the sequence and the last image going on in our minds; it also creates anticipation for the next thing Morris will show us. He’s not talking to (or worse, at) us, not lecturing us, but engaging us in conversation, and those moments of blank screen are his pauses for us to think before he picks up the thread again.

In all his films, Morris uses footage from pop culture, usually old movies and TV shows. Here, running through the whole movie and often appearing with Dave Hoover’s story, is Darkest Africa, an “even for that time, it was pretty cheesy” film starring Hoover’s inspiration, lion tamer Clyde Beatty. Also, there’s some 50s sci-fi which I’ll just assume is called When Robots Attack! Like a lot of scenes in Morris, these go on longer than needed, if all they did was convey information; also, they often don’t illustrate what people are saying. They can be read as ironic–wow, look at how stupid lion taming/robots are–but Morris’ tone is too generous, and these characters are too genuinely interesting for that. In Morris’ world, pop culture is simply the medium in which we all live and think, the system of meanings and signs that makes purpose possible. The old movies are a form of collective unconscious, our House of Being. (Stole that phrase from Heidegger, I did.) At the end, when we hear a lion called “Simba,” a new cycle of pop culture has started for a new generation of circusgoers and lion tamers, and the 2097 Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control will have footage from The Lion King.

Part of the generosity of tone comes from Caleb Sampson’s music, which could be described as fast, cheap, and out of control Philip Glass. Glass has scored a lot of Morris films (his haunting music for The Thin Blue Line was repurposed for a set of piano pieces) but his stuff would be too elegant for this film. Sampson’s music incorporates a lot of circus-like themes and rhythms; it’s closest to Danny Elfman’s score for Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure, both goofy and warmhearted all at once. It really does feel cheap in the best sense: not poorly made, but the kind of sound that’s just lying around in our culture, the way old movies do. Sampson creates a lot of propulsive energy that’s matched by the variety of images and the speed of cutting; this is a breathless, fun 82 minutes of movie. In “Eternal Future,” which opens and closes the film, the music slows down a bit and has an even greater power. It’s a classic movie cue, slow theme over fast motives, and it creates an elegiac feel that pays off in the final minutes. More on this later, but for now, listen:

The true subjects of Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control aren’t the four interviewees, and it’s not really their work–although we do get to hear a lot about that. Morris’ associative method means that what the film is about never gets directly stated, but emerges from the words and images and the way they play off each other. As the movie goes on, you can start to realize that all four people are talking about the same thing. That recognition, that ability to see common ideas underlying disparate things, is really the basis of all theory: scientific, legal, humanistic, historical, artistic. Ludwig Wittgenstein, in the Philosophical Investigations, said “the use of the word ‘rule’ and the use of the word ‘same’ are interwoven”; to say two things are the same means the same rule applies to both, and a rule is something that works for similar things. Once you start catching similarities here, themes start to emerge.

One theme would be interaction. Living things interact with other living things. Learning to deal with a lion and not so much die means learning it–we learn that the first 30 seconds in the cage will tell you what will happen. (Also, if you get attacked, do not stop your routine.) Naked mole rats interact with each other by covering themselves with shit and piss; that allows them to recognize outsiders. The craft of topiary gardening means to guide a living thing into a shape with minimal interference; programming robots means first giving them the ability to move, then the ability to recognize each other, and only then can you attempt to program a goal into them. That sense of interaction as a necessary and more fundamental part of life, more fundamental than purposeful action, keeps recurring–and of course, it’s heightened by Morris’ associative editing. If this film was presented as four 20-minute segments, one for each subject, that wouldn’t be there.

That sense of interaction goes within orders of being, and across them too:

All of this stuff is looking at Other, the exploring and finding of animals that have nothing to do with any control that we as a person would have. That feeling that you are in the presence of life that is just irrelevant of yourself, that’s the Other. And the Other is something to be feared, you know, people are afraid of new, different, strange. But to me, it isn’t anything to be feared, it’s something to be wondered at, and looked at and explored, perhaps communicated with, not to sit down and have a conversation, but to take pictures of it and to actually get the moment where the animal is actually looking at you and there’s a moment of contact: “I know you are, you know I am.” That’s not something that happens every day, you have to go out and look for it.

That encounter with the Other, the ability of living things to connect across different orders of Being, keeps coming back in Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control. (And “I know you are, you know I am” comes awfully close to a theme of another great documentary, Paris Is Burning.) Continuing with the theme of interaction, we won’t just connect with these different orders, we will live with them. By including lions, tigers (oh my), gardens, robots, and naked mole rats alongside people in this film, Morris creates another theme, the expansion of life. Naked mole rats came up because someone was looking for a mammal that behaved like an ant or a termite, a crossover between orders of being. We hear about a future where “these much more intelligent systems are gonna infiltrate our lives”; this film is almost twenty years old and that future is on the way. (In a great and typical touch, we hear that line right after an extended discourse on the value of hand shears in gardening, and the rejection of electric tools.) In the future, “it’s gonna be harder to make the distinction between living and non-living things”; one path our thinking might take will be to broaden the definition of, or at least our instinct about, what life is, and this movie provides a good way to start doing that.

As a director, Morris’ craft is a lot more visible than most documentary filmmakers. Richardson has also worked with Martin Scorsese, and Morris most resembles Scorsese in his approach to editing, montage, and scoring. Both of them use the resources of cinema the way a novelist uses language, not so much to show what happens as to give the feel of a consciousness. Marc Cooper once remarked that great artists (Scorsese and Beethoven were his examples) don’t merely convey feelings, they create feelings that are unique to them. A feeling unique to Morris, never more powerfully created than here, is that restless, associative inquiry, the sense of a mind jumping through tangents and ideas and images and things, always on the verge of theory but never quite getting there, and more valuable for that. In words, the work Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control most resembles is the Philosophical Investigations, another work that comes with insight-bombs every few minutes and makes thought and intellect as personal as emotion. It’s also just as fun as this.

Life, here, is about that interaction, about the way life, consciousness, and thought is necessarily bound up with the world; “I don’t believe it’s possible to have a disembodied intelligence without a physical connection to reality.” (That’s a very Wittgensteinian idea, who argued that language and meaning were necessarily bound up with practice.) Environment shapes life, it has to; “only in captivity do animals get to get old.” The way that environments get shaped for life, and the way that life itself gets shaped, really collapses any kind of distinction between “natural” and “artificial.”

That’s something that extends to the film itself; there’s as little distinction here between idea and action as there is between nature and artifice. In contrast to Les Blank, who films first the physical, sensual experience of life, Morris has always been a philosophical director, using the stories of others to explore ideas. The way that Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control keeps grounding those ideas in an everpresent everyday reality makes this his best and most unique work. “You have to experience an injury. You have to experience chaos”; Morris gives us, as much as a film can, the experience of that chaos and somehow these ideas emerge from that.

“The whole concept of stability is a concept of death.” In contrast, life ever changes and barely becomes predictable, whether that’s on the superquick scale of mole rats running around or the years-long pace of gardens growing. In designing robots that walk, everyone was designing them to be stable, but looking at insects led to the insight that stability wasn’t needed (another crossover between orders of being), and so robots were designed that walked by constantly falling over: they were more successful when they were like life. Instability emerges with interaction as another theme, and another necessary part of life; it’s also a fundamental aspect of the style of the film. In addition to the instability of film stocks and speeds, and with the exception of the straight-on interviews, Morris almost always shoots on a Dutch angle with no stable horizon line. That makes the shots more interesting, definitely, and keeps them away from feeling like definitive portraits of anything. He also goes for low angles to watch things in motion, like we’re one of them, interacting with them; we even get shots of the naked mole rats in their burrows. (Another of my favorite documentaries, Powaqqatsi, is about massed action, and this is about individual, chaotic action.) The film feels like something that’s happening right now, and therefore unable to settle down into anything static.

The interaction of orders of life, the grounding of that life in a realistic environment, and the way they all change has a name: evolution. Beginning with Clyde Beatty’s work as a lion tamer and his circus (a shot of Beatty’s name is one of the first images here), we hear about how that profession has changed over time. From then onward, we hear about how everything grows and changes, how people and systems try things, fail, pick the ones that succeed, and move from there: the process of selection that Darwin identified as the driver of long-scale change. It can be a museum exhibit, the programming of robots, the growth of a garden; there’s always the sense of moving towards some kind of intrinsic, independent but interacting life. These things happen over different time scales–a tree grows more slowly than robots learn–but we can still see a common process. (The use of different framerates reinforces this principle.) This isn’t a film about tools: “I switch it on and it does what is in its nature.” We can see here how, over time and through interaction, lions or robots or anything living comes to its own Being, comes to be something unique in our diverse world.

With the sense of all these rules, another unifying principle, a second order of theory, becomes clear, especially towards the end of the film: Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control is about life. Morris has made a film explicitly about space and science (A Brief History of Time), but this is his real version of Kubrick’s 2001 and at half the length. It restlessly explores what life is and seeks to define the rules by which it lives and evolves, and what makes it different from what isn’t life. (And like 2001 and HAL, it’s most interesting when it’s on the border between the two.) Morris creates as much a sense of wonder than Kubrick did, and more fun too, and he does it all without ever leaving the planet, much less the galaxy. Richard Feynman once said “nature uses the longest threads to weave her tapestry, so the smallest fragment reveals the whole design”; somehow, Morris found four people who could lead him to learn about the whole of life.

All the methods Morris uses here–the juxtaposition of one voice with another’s image, the music, the editing, the blackouts, the variance of film stocks, and on and on–all these things embed one more theme in the structure of the film itself. Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control is about thinking, about how these four men think about the world around them and how that thinking gets embedded in action in the world, but more than that, the film itself is thinking, making connections, associations, interrupted by images of popular culture, and occasionally having impressions coalesce into something close to ideas. By avoiding definitive conclusions, Morris keeps the feeling of thinking going; to have any kind of grand statement or conclusion would make this a film that speaks to us, not something that’s thinking along with us. Morris doesn’t describe thinking, he demonstrates it all through the film. (In contrast, 2001, with its slow pace and clearly defined sections, takes the form of ritual, not narrative or thought.) There are very few works that can match this on the principle of “form matches content”: this film is itself an “embodied intelligence,” what we see and what it talks about is also what it does. Morris thinks through film the way Jasper Johns thought through paintings or Eugene O’Neill through melodrama.

There’s a name for those who find joy in the process of thinking itself, who get obsessed about the things no one else knows: geeks. (The circus ancestry of the term shouldn’t be lost on any viewer here.) One doesn’t have to know or care anything about rats, robots, lions, or gardens to appreciate this film, but anyone who has their own obsessions, anyone whose mind makes connections that are absurd and dissonant and once in a while valuable, anyone like that will find themselves in Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control.

It has nothing to do with science; these are not scientific observations. I look at them strictly from the point of self-knowledge, learning not only about them but about myself from the way they react and act towards each other.

Maybe all our favorite works reflect something back about ourselves. Morris isn’t making a definitive statement about the world–in fact, to do so would violate one of the themes here, because it separates “the world” from how we live in it–he’s showing the energy and, finally, the wonder of how we find pattern and meaning in that world. (Carl Sagan’s Cosmos is another work that’s close to this one, and even longer than 2001.)

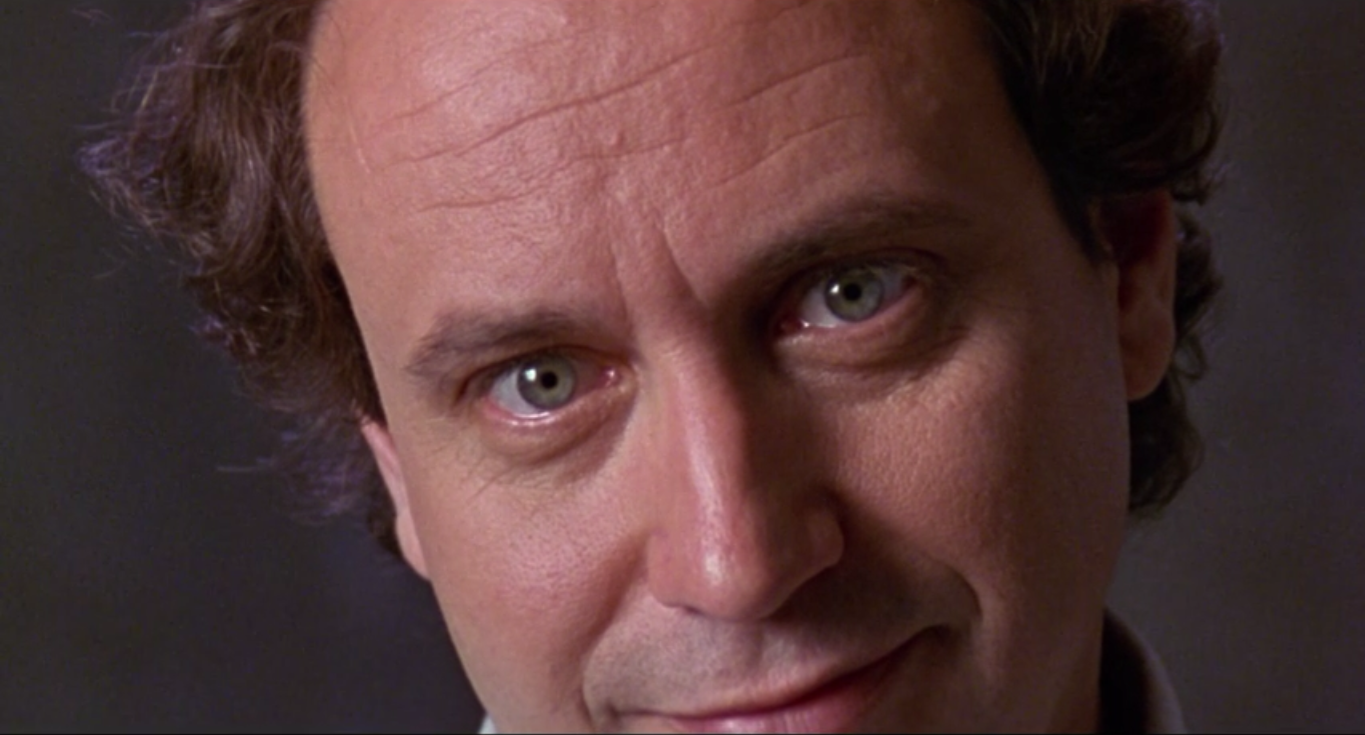

Amidst all its fun and energy and wonder, Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control doesn’t reveal how effortlessly profound it is until the final minutes, as “Eternal Future” comes back and the subject necessarily switches from life and growth to death. The music tells us: the future is eternal but we are not, and to be alive is to not be part of the future. Before the ending, we already hear about “the expendability of the individual,” about how complex systems incorporate death as part of their evolution, and how they have to do that. Now that idea moves from systems theory to something more basic: the limitations of being alive, not being able to start work on another animal because you won’t live long enough to finish. People talk about the next generation, and it’s difficult: “I’ve had several understudies but they lose interest in it.” Morris shifts the old movie imagery into full pop-culture Apocalypse, accompanied with the stare of Brooks the roboticist. (Morris shoots Brooks closer to the face than anyone, the way one shoots a mad scientist; I read this as unfair until I realized that Brooks lives up to the role: he will make the new future.) No matter what we do, we can’t change that; this film about life closes with a meditation on death, because that’s what life does. (Morris ends the film with a dedication to his late mother and stepfather.) In Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control and in life, we act, we think, we apprehend patterns and make sense of the world; we evolve with other living things, and one day we won’t do that anymore and the world will keep going on without us. That’s a source of wonder too.

“As long as I’m alive I’ll take care of it. I don’t know what happens after that.”