Sam Elliot shot his mouth off just in time for me to kick off this essay.

If you have missed it, or you’re looking at this essay from any time and distance, I’ll catch you up. Elliot appeared on Marc Maron’s WTF podcast and had Opinions on Best Picture contender The Power of the Dog. “What the fuck does this woman from New Zealand know about the American West? And why in the fuck did she shoot this movie in New Zealand and call it Montana and say this is the way it was? So that fucking rubbed me the wrong way.”

Hollywood movies are, of course, known worldwide for their accuracy and attention to detail.

Elliot was rightly dunked on for the hot take, but the whole thing reminded me of why I signed up to write this essay in particular.

But let’s go a little back in time.

When I was in high school, there was a list of books we were supposed to have read in preparation for college. It was one of those photocopied lists, passed on by well-meaning folks who wanted us to get good SAT scores so we would get into good colleges.

I read a lot of those books. Some of them I liked. Some of them I loved. Some I loathed. A few I read through without them really registering; I bounced off Thomas Hardy so hard that the only thing I remember about The Mayor of Casterbridge was that for years the only thing I could remember about The Mayor of Casterbridge was a detail about one character’s horse that I have since forgotten. (I do suspect that said horse was the only likable character in the book, but maybe I’m just being cynical.)

I don’t think you need me to tell you that the ‘canon’ I was recommended was predominantly English-language, white and male. I also don’t think you need me to tell you that many of these books have fallen out of favor and many of them were never much good.

The idea of the canon and what it should be has gone through many rounds of debate. A canon is usually proposed to give an individual a common understanding of culture or art (sometimes both), and there is a certain appeal to that. People have probably always used cultural references as shorthand, whether it be referring to a “Romeo and Juliet” situation or cracking jokes about “who’s gonna tell him?”

But there cannot and never has been a true common understanding. It’s impossible. Anyone reading a British murder mystery written between the 1920s-1960s has probably watched a reference or two fly right by, and I cannot even begin to tell you the frustration at the end of Dorothy L. Sayers’ Gaudy Night when Lord Peter proposes—and Harriet Vane answers in Latin. This was long before the Internet; as I recall it took me years to figure out what they’d actually said.

What the canon all too often represents is not common understanding, but a common method of exclusion. If you didn’t know the Latin at the end of Gaudy Night, maybe the book wasn’t for you at all. (A lot of early British detective fiction is classist at best.) The critic Harold Bloom’s “Western Canon” named only 26 writers at its center. While there are virtues to this—anyone can sample 26 writers—the inevitable omissions are obvious.

The minefields of racism, sexism, classism and homophobia are clear enough that I don’t think I need to belabor them. And honestly, I think that is not in fact the thing that kills the notion of ’the canon.’ The canon could be expanded or recreated, after all, and many attempts at doing just that have been made.

But my problem with the canon is more fundamental than that.

A canon leaves no room for upstarts, for non-geniuses, for noodling around in the weird margins of things until you find something to stick with. It emphasizes pioneers and singular geniuses, and forgets about refiners, communities, and the joys of dead ends. It frames art as something static, and insists that common understanding can only be found through a few narrow channels. It can’t be fixed, because the whole thesis is so fundamentally flawed.

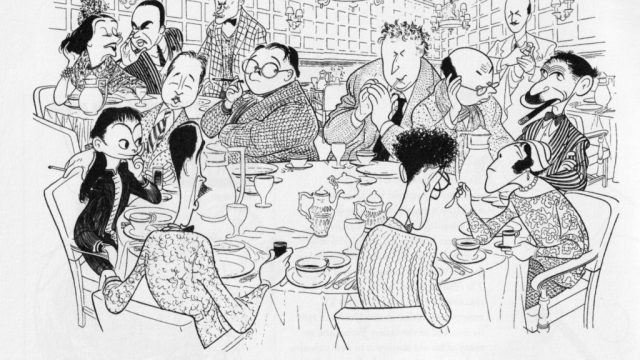

One of the things that has really struck me over the years is how many of ‘the greats’ worked in or against their community. Lord Byron wrote whole poems trashing his artistic rivals and also had literary friends and lovers who pushed each other to new heights. TV shows have writers’ rooms. Shakespeare had more than a half-dozen competing theaters, mounting plays by Marlowe and Ben Jonson, among others. The history of music is one of borrowing, transforming, and re-creating.

The canon strips that complexity away. Instead, there is only Genius, and it is rare and near-unreachable. Since the 1200s or so there have only been twenty-six authors needed to unlock the mysteries of Culture, two or three of whom were alive in your lifetime. (All the rest of you can go home.) No one influences each other, no one challenges each other. Sure, Shakespeare took the storyline of Romeo and Juliet from an existing play, but forget that, because Shakespeare was a singular genius.*

The idea of the canon—the ethos of exclusion—enables and enforces some of the most toxic ideas of culture. Gatekeeping, the false dichotomy between high and low art, even the myth of the solitary genius. It tells us that a Western can only be one thing, a story about white cowboys in Texas who never, ever thought about kissing each other.

It also enforces a certain cultural illiteracy of its own. Without reading at least a little of the regrettable poetry of Robert Southey, how can you possibly enjoy the brutal evisceration Byron gives him in Don Juan? Is it really ideal to give the impression that Shakespeare happened, and then everyone in the English-speaking world just lumbered along for a bit? Do we just pretend Sally Menke came fully formed out of the earth to earn Oscar nominations, or are we allowed to talk about the editing work she did on Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (1990)? Because let’s be real, it’s what got her the job, and there are damn good reasons why.

The hard truth is that humanity has been telling stories since we had the language to tell them, and we’ve been writing them down since we figured out how to scratch onto birch bark or into some soft clay. The good news about never running out of something to watch, or read, or listen to is accompanied by the bad news that no single person will be able to understand the whole of human experience; it’s simply not possible.

Are there some things that are necessary to experience to understand art? I do think so. If you asked me if there were certain things every person should experience, I would absolutely have a list. But so do you. And I’m not sure my list really is better than yours, or will help you navigate through the oceans of the Arts. And that’s fine. What’s more important is where we come together to find a mutual understanding. And you don’t need a photocopied list to do that.

* I mean, he was. He just isn’t the only singular genius. There’s no such thing, that’s the whole point here.