Fruits Basket by Natsuki Takaya is one of the highest selling manga series in both Japan and the U.S with over 30 million copies sold. The final volume of the manga remained on New York Times’ manga bestseller list for 12 weeks, one of Tokyopop’s most successful series. It’s the story about a young high school orphan, Tohru Honda, who suddenly finds herself as a guest in the home of the wealthy and mysterious Sohma men. After accidentally embracing them, Tohru discovers their secret – cursed members of the Sohma family turn into a member of the Chinese zodiac of lore when hugged by a member of the opposite sex. Tohru vows to help them break their curse, while also caught up in a love triangle between Yuki and Kyo Sohma. The premise of Fruits Basket, lovingly nicknamed Furuba, is wild. Even so, Fruits Basket touched the hearts of a generation. As the reboot of the anime is about to enter its second season, I thought this would be a great time to talk about what makes Fruits Basket so special in the first place.

Whereas the 90s saw a rise in shojo manga featuring magical girls, a powerful cultural shift that recognized female empowerment, Takaya’s work exhibits a variety of characters that don’t fit into any one mold of femininity. While not always physically strong, these characters nonetheless found internal strength through their bonds.This is best portrayed by the heroine, Tohru, and her best friends, Arisa and Saki. Tohru is the heart of the manga. She is a character society has deemed is “too” much. She is too blindingly optimistic, too ditzy , and too empathic. She is often framed as maternal, and is incredibly polite. While characters with such “feminine” qualities tend to be passed off as passive, Takaya shows us that kindness takes courage. It is also essential. When faced with what most would consider a monster, Tohru chose to be vulnerable. Tohru also constantly stands up for herself and her convictions, even under the threat of physical violence from the mysterious and incredibly wealthy head of the Sohma family, Akito. In fact, the one true time Tohru ever showed anger was when Kyo assumed what she wanted in a situation. Tohru is also deeply aware that who she is does not fit into social norms. Over time, it’s revealed that some of her polite habits are performative, a way to cope with her deep anxiety. Throughout the manga, Tohru slowly learns to become more confident in the woman that she is – one that embraces these incredibly important “too much” qualities.

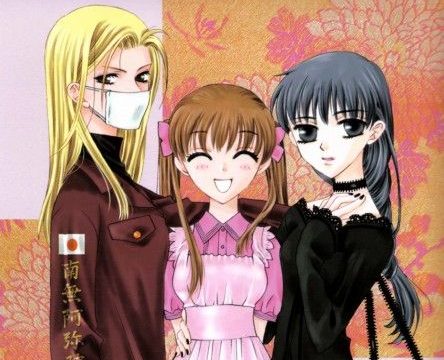

Both of Tohru’s friends are also “too much.” Arisa is loud, brash, and easily moved to emotion. However, this only amplifies her empathetic, loyal, and intuitive nature. She’s often the voice of reason when she’s in the room. Although reformed, Arisa still wears the signifiers of her former sakuban gangster life- blonde hair, thinned brows, and a customized school uniform. Tall, Arisa cannot help but to stand out. Tohru’s other best friend, Saki, is a psychic, dedicated to wearing only black, usually in the form of gothic lolita street fashion. Calm and darkly sarcastic, Saki is unabashedly blunt and aloof … to the point of hindering her school career, putting little effort into academic and athletic achievement. There’s a wonderful scene where she dramatically collapses at the start of a school run, and ends up gathering a group of other underachievers to play Old Maid. Takaya presents these girls as an odd trio – but a happy and thriving one that embraces their own brands of femininity.

Further, Fruits Basket sincerely explores how femininity is not just restricted to cis girls and women. Momiji Sohma likes to wear girls clothing because he felt the styles were cuter on him. He wears a hybrid uniform to school, his cousins even fighting the student council in his defense. He’s also often unafraid to be vulnerable, often at Tohru’s side as a shoulder to cry on. Then there’s Ritsu, another member of the Sohma clan. To Ritsu, women’s clothing isn’t just a fashion choice – passing as a woman is comforting to them, and helps with their anxiety issues. It’s simply part of who they are. This topic is admittedly dealt with awkwardly in the manga- a side character will joke about how shameful Ritsu is, when the next sympathizes with the social pressure Ritsu faces. Nonetheless, most of the family accept Momiji and and Ritsu simply as is – and Tohru loves these characters for who they are, often their loudest advocate. Honestly, this was some of my first exposure to the concept of non-binary and transgender individuals in media, and I’m grateful that it was an experience that was mostly emphasized by love and acceptance.

That just barely covers the complexity of the cast. Their lives are complicated and intertwined- these details truly bring them to life. The intense focus on character development truly drives the story of Fruits Basket. It’s what sells the absurd and terrifying concept of an intangible curse that binds the Sohma family together. Takaya is a master of pacing. Serialized manga does not lend itself well to slow paced stories – it’s a very competitive market that demands keeping your audience’s attention, often with dazzling gimmicks or intense cliffhangers. Not to say Fruits Basket doesn’t have its moments of shock – but Fruits Basket allows their characters to breathe and work through their emotions, often leading to steller pay offs. Perhaps one of the best examples of this is the manga’s antagonist, Akito Sohma.

Cursed to be God, Akito largely carries the weight of the curse. In the first few arcs of the manga, we only see glimpses of them – a shadowy, sickly figure, always closely guarded. Even so, the roots of the psychological trauma that Akito has inflicted on the family runs deep. What seems like a silly rivalry between Yuki and Kyo unravels itself to be a heartbreaking conflict of their fight to claim their own humanity and independence. Akito is also physically violent. Rin is tortured. Hatori had been rendered partially blind in the past. Kyo has the very real threat of eternal imprisonment looming over him. Through violent anticipation, Takaya truly transforms Akito into a vengeful god – seemingly impossible for Tohru’s methods to penetrate. And yet, as Shigure mentions early on in the manga, the curse is decaying.

About 2/3rds of the way through the manga, something shocking happens. Kureno, one of the members of the Sohma clan Akito has a tight grasp on, revealed he had actually freed himself from the curse long ago. Further, Akito is actually a woman, forced to portray a masculine god. From there, Takaya removes the curtain of mystery, which Akito used as a weapon. Without that protection, Takaya shows the audience a pathetic, jealous, and ultimately lonely individual. But a major theme in “Fruits Basket” is healing through community – and Takaya masterfully breaks down her villain only to surprise us by having them put in the work towards redemption. It’s Akito whose internal journey ultimately breaks the curse. It’s Akito, who, by embracing their true self, dismantles the system they profited from. Even then, Takaya acknowledges that the path towards healing is messy. Not everyone can forgive – even after Akito speaks at their last banquet, Rin cannot accept their apology. Fruits Basket offers no easy answers, but instead challenges its audience to attempt to tackle problems through empathy.

What sells this emotional tension so well is Takaya’s art work. The art of Fruits Basket is incredibly expressive, especially in the way Takaya captures faces and utilizes negative space to show extreme and complicated emotions. She also has a talent for capturing physical humor, often through martial arts. There’s an interesting noticeable shift halfway through the series – where as the first half has heavier textures, the second half of the series features smoother lines and cleaner, blockier colors. Takaya had broken her hand, and her style changed as a result. I personally love the art from the second half of the series more – it captures both the maturity of the plot and the characters, versus the more traditional shojo style she utilized at the beginning of the series when the protagonists were at the start of their emotional journeys.

Fruits Basket is ultimately about healing. Whereas most shojo manga focus on romance as the ultimate goal, romance in Fruits Basket can’t heavily develop unless characters were working through their personal journeys with the help of those around them. In Fruits Basket, everyone deserves love, and everyone deserves a chance to grow. That was a powerful message to middle school me, who didn’t quite fit in. It remained a pillar of light for me later, during rough times. Even now, I have a deep fondness for the characters – the new reboot anime tugs at me emotionally in a way nothing else does. Fruits Basket is a beautiful reminder that not only is empowerment about the freedom to be, but that optimism, vulnerability, and empathy are strengths that bring us together as people.