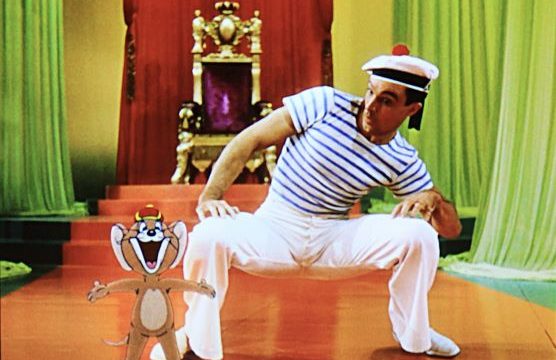

It’s popular to refer to certain movies as “live action cartoons.” Doubtless when Mousetrap, for example, was developed, the people who made it watched a lot of Looney Tunes and so forth to get the action as similar as they could while still allowing for, you know, actual humans. And it’s true that those movies are based on a very specific kind of cartoon—Looney Tunes, again, and the early Disney shorts and so forth. On the other hand, the physical comedy of cartoons in turn tends to draw on early silent comedy shorts for a lot of its tropes.

When The Simpsons told us that, before Itchy and Scratchy, all cartoon characters did was play the ukulele, that wasn’t quite true. However, it did have a grain of truth—very early cartoon shorts weren’t all that interesting. It’s not necessarily the violence that improved them, but the artform progressed as they started taking on beats from the live action comedians. Yes, some of those are violent, but by no means all of them.

The tropes continue to this day. Exaggerated reactions, for example, were originally plays to the camera in the days where people were figuring out how to play for the camera instead of the back of the house. Even the violence stems from things like Charlie Chaplin closing doors in people’s faces and shutting trunks on their beards in “The Cure.” And I’m sure Chaplin’s actions had their own origins in things like vaudeville and the music hall tradition, but the cartoons were playing on what the public saw, and it became entrenched in the cartoons.

Possibly the reason fewer people notice this these days is that fewer people watch the shorts. Oh, you don’t have to dig very far to find devotees of Safety Last! However, it’s 74 minutes long—ten minutes longer than Dumbo. And the tropes are there, too, of course, but they’re quite clearly in service of a plot. Oh, there’s something of a plot in some of the shorts, but mostly, it’s about the gags. Which is fine, but it means that the gags aren’t as well remembered except big set pieces or prominent things that didn’t appear as recurring bits and are mostly done as deliberate tribute.

It may be that some of the recurring bits of animated comedy started out as deliberate tribute as well. Possibly 1930s audiences, in the early days of animated comedy, would recognize a bit as originating with Laurel and Hardy, and modern audiences don’t because they’re not as familiar with the duo. Part of the problem with the lack of familiarity with the shorts is that there are comedians who did essentially nothing but shorts, and we’ve lost them as a culture.

This, in a way, is how the history of the arts works. Things survive in ways we can’t predict. I could, if you cared, tell you how the history of how the ballad influenced later pop culture, most particularly the broadsheet, and how that ties into modern entertainment (and if you pay me on Patreon or Ko-fi, I absolutely will), and that’s just one other example. Shakespeare started playing around with requirements that went back to Greek drama, and we’ve been playing with his changes since then. But perhaps it’s time to talk about this history.