For all readers and Ellroy fans out there: John and Grant co-hosted a LIVE reading of Widespread Panic and Q & A with James Ellroy himself on the evening of June 22nd, also featuring Ellroycast veterans and Solute favorites Zoë Z. Dean and Joan Renner. Click HERE for the whole scoop!

The point is that Elena remained remote most of all to herself, a clandestine agent who had so successfully compartmentalized her operation as to have lost access to her own cutouts. (Joan Didion)

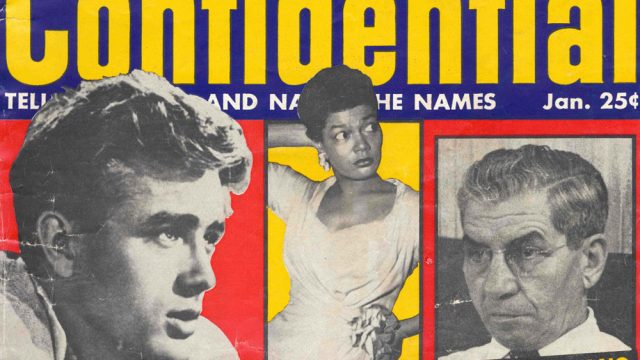

John: Peepers, prowlers, perverts and pederasts take pause: Widespread Panic denotes a dynamic departure from the Demon Dog’s depraved descriptions of institutional power. First off, it begins in Purgatory, not L.A., where its main character, infamous Hollywood P.I. Freddy Otash, gets poked with pitchforks by the souls of those he either publicly humiliated through the tabloid Confidential or who he privately blackmailed. It is also James Ellroy’s first full-length book written in the first person since 1992’s White Jazz, which allows him to jettison the multi-narrator structure and conjoining story arcs that define his trademark style. Widespread Panic also puts 1950s Hollywood, rather than the L.A.P.D., at the center of the narrative’s focus. This move invokes a voice that mimics the period’s tabloids, which was chock full of alliteration, repetitious syntactical gags, and hipster jive. This brings us to the biggest divergence from the Ellroy norm: it’s fuckin’ funny, pushing jokes ahead of the violence and psychological angst typically found in the author’s oeuvre.

The book is a fictional memoir told with a reckless verisimilitude that is radical even by the author’s usual standards. Ellroy begins with a condensed rewrite of the e-novella “Shakedown,” which charts Otash’s professional development as cop, criminal, and Confidential dirt digger. In order to fulfill his voyeuristic proclivities, Otash makes crossing the lines between the law and criminality his métier. He adroitly busts thieves while in uniform while masterminding burglaries and wiretaps when he goes off the clock. He extorts celebrities like Johnny Ray and Marilyn Monroe for their peccadillos yet orchestrates fake heterosexual romances to keep Rock Hudson closeted. In constructing and demolishing the walls dividing the public images and private lives of Hollywood (and D.C.) personages, Otash subjectively encapsulates the ethos of celebrity culture. As you’ve pointed out in our conversations, Grant, this book details how the public’s memory of showbiz is opportunistically built, destroyed, and reinvented, and how the “beautiful people’s” fear of social censure drives the revisionist dynamic.

The rest of the book consists of two new, much longer novellas. The first, “Pervdog,” finds Otash solving the murder of a cop assailant’s widow who Otash executed, against his conscience, under L.A.P.D. sanction. The recently deceased Jane Horvath turns out to have been an informant for the F.B.I. who had infiltrated a communist party cell in the 1930s. The group’s tentacles extend into the 1950s, influencing Freddy’s shakedown of B-movie-hunk-turned-smut-auteur Steve Cochran. Complications further ensue as Otash falls for the cell’s leader Connie Woodard, Jane’s ex-lover, and a comely, amoral Jewish assassin, who sports a murderous vendetta against another cell member. The second, “Gonesville,” weaves an alternative history to the making of Rebel Without a Cause, in which Otash attacks a fascistically fetishistic method acting cult headed by director Nicholas Ray, who plans to transform James Dean, via method acting mind control, into the avatar of celebrity serial rapist Caryl Chessman. As with This Storm, Ellroy bends historical fact to the dictates of his moral narratives.

For all of its oversized outrageousness, a melancholic note underscores the novel’s jocular vibe. Freddy’s odyssey of sex, scandal and murder, like that of White Jazz’s Dave “the Enforcer” Klein, generates consequences, with a bevy of worldly B list actresses, future movie stars and political king pins dumping him on grounds of moral turpitude. Otash is also haunted by the casual abandonment of his moral compass. Otash says he draws the line at murder (and working with communists) but commits the former early on in his (short lived) law enforcement career. His alliance with Connie Woodard signals the possibly redemptive promise of breaking the other oath. In White Jazz, one senses that “The Enforcer” finds grace. Freddy, on the contrary, seems irredeemable. His confessions lack contrition and his behavior seems rooted in the nature of his personality.

I’ve been emphasizing, so far, some of the book’s deviations from Ellroy’s previous long form fiction. Grant, do you think this is too radical an assessment? Do you see more continuity with key themes in the author’s work, or a further development of ideas in his more recent output?

Grant: Ellroy pulls a move here that he’s done throughout his career: shift characters from minor status to major and back between novels. Freddy Otash appeared in earlier books (particularly the Underworld USA trilogy) not so much as a minor character but as local color, one more operator in a world of them. The radical nature of Widespread Panic doesn’t come from any shift on Ellroy’s part–it’s morally in continuity with the direction he’s taken since Blood’s a Rover–but from bringing an earlier kind of character into his current storyteller’s morality, and as you noted, giving the entire work over to that character’s voice. Otash resembles the Kemper Boyd of American Tabloid (the man bent on realizing the American Dream in a criminal underworld) but this book is anything but the stripped-down, action-exclusive story there (although this is way more of a tabloid). The difference between this and Ellroy’s previous works actually comes from the continuity: this is recognizably the same Otash that Ellroy wrote about over 20 years ago, it’s the author who has changed. Rendering Otash’s consciousness into alliterative, Confidential-style prose, Ellroy creates his version of Gene Wolfe’s Peace: the afterlife confession of a man who fundamentally doesn’t get it, where regret is a function of the language rather than any action. We finish both books knowing this guy ain’t getting out of Purgatory this trip.

Right at the beginning (or I guess, since it’s in the Purgatorial introduction, the end), Otash states one of Ellroy’s most consistent principles: “I think and write in algorithmic alliteration. Language must lambaste and lay on the lash. Language liberates as it offends.” Ellroy’s best work has always been marked by that unity of language, character, and action: the frenzy of White Jazz, the action liturgy of American Tabloid, the swooning Romanticism of Blood’s a Rover and This Storm. (His not-best work results from the failure of this unity: The Cold Six Thousand’s language couldn’t give us the emotions of its characters.) Superficially, Panic resembles the Danny Getchell stories of some years back, but those were tossed-off exercises, and there’s a melancholy here that’s equally expressed in the incidents and the prose. Ellroy shows us this right away in the first on-Earth scene, 70-year-old Otash recounting the Good Old Days in a Beverly Hills deli, and getting a coronary in the middle of it.

The booth roared and re-roared. Julie Slotnick gasped for breath. Al Wexler yukked out a bagel chunk. It flew and flopped to the floor.

Alky Al owned six porno bookstores and nine nose-job clinics. He plowed a truck full of migrant Mexicans and left six dead. I got it mashed down to a Mickey Mouse misdemeanor. Al owed me, laaaaarge.

I killed my sandwich. Alky Al blew a faux fanfare. I laid out my lifelong credo: “I’ll do anything short of murder. I’ll work with anyone but the Reds.”

Ellroy then pulls a Lost-style move, as the next scene shifts back to 1949 and his murder of Ralph Mitchell Horvath (which will bring him into the world of Joan Horvath in the second novella): “He tried to say ‘Please.’ This dream’s a routine reenactment. The details veer and vary. The ‘Please’ always sticks.” The triple opening, moving back in time from the latest to the earliest incident, shades everything that follows and says who Otash is and how he thinks: An entirely transactional man, who can only see the world as opportunities and headlines, the best dealer of information because that’s all he can see.

Panic starts off in that rollicking Getchellian mode (John, as you noted, it’s often very, very funny in this way), with Otash celebrating his Sy Devore suits and three-ways featuring Elizabeth Taylor, but gets progressively sadder. Ellroy gives Otash some of the romantic longing that he’s described in his autobiographies (especially The Hilliker Curse, which seems more and more like the Rosetta Stone of his later books), but it’s never fulfilled here; and for all Otash’s dealings, he winds up getting used by just about every institution he encounters, from the studios to the L.A.P.D., the last in the person of Bill Parker. (How Parker effectively captures and turns Otash into a snitch at the end of “Pervdog” is one of the most compelling scenes here; you can feel a steel door slamming on Freddy’s fate.) An early exchange here looks like an opportunity, but it’s a warning: “Hollywood could use a guy like you.” (Otash’s reply, “You mean I could use Hollywood,” turns out so, so wrong.) At the beginning of his career, Ellroy deliberately abandoned writing about that staple of crime fiction, the private detective: now, after almost 40 years, going all-in on that character, Panic feels like the embodiment of the famous final line of Raymond Chandler’s “Killer in the Rain,” with a twist: Otash is tired and old and of use to everybody.

The connection to the Dave Klein of White Jazz goes further than the first-person narrative: even more than Klein, Otash makes the world that will eventually consume him. In a great early scene (Otash is never more enjoyable than when he’s scheming), he lays out to Robert Harrison, Confidential’s editor-in-chief, how the ecosystem of celebrity has changed, and how he can give the magazine the dirt–the resources–it needs to thrive in the new world. (“My two salient points are these: you must dramatically boost your sexual content, and everything you publish in Confidential must be entirely true and verifiable.”) That’s 1953; by 1957, Otash has become a J. J. Hunsecker figure, a hedge-fund manager of gossip, with minions trying to get in his favor by bringing rumors to his table. (“Orson Welles killed the Black Dahlia” is a running gag.) At times, this feels like The Wolf of Wall Street: the city, industry, and decade may be different, but it’s the same story of an entrepreneurial outlaw who ends up as the empty avatar of an essentially capitalist system, where the more you produce, the more you need.

As much as L. A. Confidential covered the growth of the institution of policing in the 1950s, this covers the growth of what we now call the entertainment-industrial complex. (Freddy sez “WE CREATED TODAY’S TELL-ALL MEDIA CULTURE,” and he’s got a point.) John, with both institutions, you know the historical details better than anyone else around. How does Ellroy use the historical record here? He’s never given over a book so completely to someone who lived in our world; what else has he imported into his narrative, and what does he do with that?

John: Throughout his career Ellroy has depicted historical events culled from impressionistic images of his pre-adolescent psyche. T.V. shows and his father’s repository of celebrity gossip are his archives. Freddy’s relationship with Lois Nettleton in “Gonesville”, for example, was inspired by the sweet desperation of her 1960 performance as a woman living one cat away from spinsterhood on The Naked City episode “To Dream Without Sleep”. In his memoirs the author candidly confesses that his erotic fascination with actresses forged early adolescent fantasies that refashioned the trauma of his mothers 1958 murder.  In a similar vein, Caryl Chessman’s notoriety provided young James with a shadow explanation for that fateful night on King’s Row. History is personal, but instead of race, class, and gender (the troika of modern identity politics) Ellroy’s conjures the mediated hyperreality of mass media, celebrity culture, and pulp magazines for metaphorical, if not historically accurate, truth.

In a similar vein, Caryl Chessman’s notoriety provided young James with a shadow explanation for that fateful night on King’s Row. History is personal, but instead of race, class, and gender (the troika of modern identity politics) Ellroy’s conjures the mediated hyperreality of mass media, celebrity culture, and pulp magazines for metaphorical, if not historically accurate, truth.

Judging from the popularity of the scandal mags, men’s magazines and other “true confession” style journals of the post war period, Ellroy’s appetite for salacious content was widely shared across American culture. Although accounts chronicled in the 50s tabloids alluded to acts that challenged community standards and occasionally transgressed the law, they were seldom explicit in their details, and often key participants’ names were omitted. Their slangy style and alliterative wordplay teased and complemented their readers’ hipness to the veiled truths concealed behind the hallowed curtains of Hollywood’s (and occasionally Washington D.C.’s) P.R. machine. The necessary duality of concealment and revelation exalted in the tabloid style defines the male gaze of lowbrow culture–the former action framing the other for the purpose of pleasure, interpolating its readers as voyeurs. As Otash holds court at the now famous Googie’s Diner, catching items from his snitches, he becomes aware of the collapsing distinction between seeing and being seen, of beholding icons and becoming one himself. He has entered the Movieland hall of mirrors.

And the business of maintaining those mirrors was changing. During the film industry’s golden age, social approbation brought about censorship boards and condemnation from The Legion of Decency. Attention directed at drug addicts (Wallace Reid and Mabel Normand) and presumably murderous sex fiends (Fatty Arbuckle) interfered with film distribution and the vertical integration of studio filmmaking. Studios contained gossip by inserting morals clauses in actors’ contracts, sculpting highly complimentary pieces in the press and courting friendly journalists. Widespread Panic takes place after the 1948 Paramount Decree, which forced studios to divest their theater chains from the production and distribution functions, and the settling of lawsuits filed by Olivia de Havilland and Bette Davis that ended the 7 year studio contract. Celebrities lost the protective cover of the company “fixers” to protect their image from tabloid journalists and investigators like Otash. Widespread Panic depicts how public relations was entrepreneurially transformed during the waning era of classic Hollywood.

As with This Storm, this new book conveys the dissolution of hierarchies and boundaries, and the identities signifying fixed borders between the watchers and the watched. Ellroy insists that this new era of image maintenance was entirely transactional. Movie stars (or their agents) could pay the publishers to “kill” stories or plant false ones (as in the Rock Hudson marriage series). Sometimes negative stories could reinforce an actor’s street cred. Rory Calhoun always said that the leakage of his teenage police record helped solidify his bad boy screen image. They could also be extorted so as to keep their dirty laundry hidden. Such actions erased distinctions between the jobs of reporter (or, more specifically, the dirt digger) and star. Elizabeth Taylor and Otash set up her husband in an adultery sting operation and they jump into a three way as a perk. Whereas the L.A. Quartet and the first two books of the Underworld U.S.A. trilogy chronicle the solidification of political institutions, Widespread Panic is Ellroy’s first try at defining capitalism as a force of categorical deconstruction.

Although Ellroy, not surprisingly, shoots its sharpest barbs at the foibles of the Hollywood Left, Marx’s notion that capitalism dissolves social distinctions into thin air is vital to the novel’s process. While Ellroy mocks Ray’s method acting cult, which declares that motivation provides professional self liberation from bourgeois society, his need to conjure the secret history behind the headlines requires the dissolution of traditional historical disciplinary practices. In abandoning having his characters pursue their goals in the shadows of verifiable events (like the J.F.K. assasination in American Tabloid), Ellroy creates new ones, such as the riotous assaults on sororities and liquor stores by Rebel’s cast, as well as an L.A.P.D raid on Ray’s “pleasure dome” at the Chateau Marmont. Thus, Ellroy returns to the cloistered imaginings and fantasies of his traumatized adolescence. Otash is by no means, outside of a penchant for voyeurism, an author substitute, but a vehicle for modernizing the form of the historical novel through personal insight. Grant, what do you make of this book’s transformative move in the use of history?

Grant: Ellroy continues to shape his stories with large and historical themes; to get a little more specific, the first L. A. Quartet has the L.A.P.D., the Underworld U.S.A. trilogy has organized crime, and here, like you said, we have the business of movies and gossip. (The capitalist nature of this last one is in its mononym, especially contrasted with the preceding two: policing is the Job, crime is the Life, and movies are the Industry.) He plays that theme more clearly than before, and that’s categorization more than praise. His preceding books have been historical epics, creating iconic fictional characters that don’t so much live through history as live out their own stories with historical elements worked into the narrative. Otash is less an icon of his time than, say, Dudley Smith, Ed Exley, or Wayne Tedrow Jr., and more of an example of it: he doesn’t have the same life outside the novel the others do, and shouldn’t. (That opening at the deli makes it clear Otash never did and never could leave his era.) He’s one more of the dense details here, which are often the most true at their most insane. (This may be a general principle for novelists.) Rather than an epic, Ellroy has written his first large-scale work of journalistic fiction here, where the primary goal isn’t plot or character but to claim a specific time and place for himself and give it to us, a gonzo reading of Hollyweird with Otash as his own Hunter Thompson.

Part of the fun of Panic is how Ellroy renders everybody as part of the game, just as everyone in Underworld USA was some kind of criminal. Steve Cochran and Nicholas Ray are the same kind of person, with the same kind of megalomaniacal artistic delusions, and there’s no difference here between Cochran’s postapocalyptic porno Thirteen Women and Only One Man in Town and Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause. In fact, Cochran comes off as the more successful of the two, as he gets the upper hand on Freddy and Ray doesn’t. Every filmmaker here comes across as Ed Wood (the Solute endorses the cool critical crime of ignoring the canon) and this leads to some recurring Ellrovian morals, as always not stated, but embedded in the structure of the work: you can only get outside of the game at great cost, and gestures, however grand, are not commitment. What distinguishes this from his novels since Blood’s a Rover is that he’s rendering a world (and a narrator) that’s all grand gesture, and the committed figures (Bill Parker, Joan Perkins, Lois Nettelton) are only passing through it; Parker in particular feels like the Hoover of American Tabloid, less a character than a force that cannot be negotiated away. If Otash feels sometimes like the least interesting character here, that only helps the unity of the world that’s his life and our gossip.

That sense of everything as sensationalized rumor, everything as transactional, falls away at a few striking moments in Widespread Panic and suggests a deeper history, one that can’t be bought or sold. Twice early on, Otash and many celebrities gather on rooftops to get loaded and watch the atomic bomb tests, far to the east; these call up Don deLillo’s Underworld, specifically its beginning and the intersection of celebrity and existential threat that defined perhaps the entire decade, but filtered through Otash’s distinct tabloid vision:

Bombs Away, Motherfuckers!!!!!

A magnificent mushroom cloud morphed into mauve and pink. Man, what a suck-your-soul sight!!! My balls contracted. My boys and I jumped off the roof, down to ground level. Ground zero popped pink particles high in the sky. The gilded gang applauded and roared.

The other memorable passage is Widespread Panic’s extended ending, the execution of Caryl Chessman, who has a cameo role in “Gonesville.” In terms of plot, it’s an unnecessary scene (the only plot point is Lois Nettleton leaving Otash) and Ellroy isn’t much for those. He slows down the pace here and lets us join Otash in witnessing Chessman’s death; the tone calls up the final pages of Ellroy’s preceding novel This Storm, Kay Lake’s heartfelt appreciation of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony. (With its placement of melancholic passages next to goofiness without discontinuity, as well as its ability to tune a degraded language into lyrical power, Widespread Panic takes Shostakovich as its presiding spirit.)

Ellroy conveys a true history here, the kind he used all through L. A. Confidential; not the conspiratorial world of American Tabloid but one where a different timeline of “verifiable events” is what matters. deLillo saw the Cold War beginning in Yankee Stadium with Branca’s Shot Heard ‘Round the World; Ellroy gives us Chessman’s execution as the talisman of the confluence of crime and celebrity that defined an entire generation’s culture, and Lois Nettleton as its underground, unidentified voice. (Contributing to that true but hidden history: Ellroy gives all the chapter titles as Otashed locations, often repeated: “The Security Office at the Sleazoid Hollywood Ranch Market,” “Atop Mattress at Jack Kennedy’s Boss Bungalow at the Beverly Hills Hotel,” “Rogue FBI Field Facility: Office Building at Wilshire and Mariposa.” If there’s a true timeline and true cast of this history, there’s also a true map to it.) As Thomas Pynchon did in Slow Learner, Ellroy has openly testified how his readings as a youth built up this vision of a secret world, not one that was hidden but where the coordinates of importance were different; he’s now fully committed to rewriting our shared past with this personal vision.

John, I’ve discussed how this fits into Ellroy’s history and his works; how would you pitch this to someone who isn’t familiar with Ellroy, or knows him only by reputation? We’ve placed him not so much in the tradition of crime novelists, but the history of “Los Angeles Intellectuals”; how does Widespread Panic contribute to that?

John: I think that most readers see Ellroy as part of a “noir” tradition of crime fiction. His novels come off as denser, grittier and less circumspect recreations of classic books and films from the 1930s through the 50s. The movie Chinatown resembles what most people think Ellroy is going for. Conflating noir and noir-inspired is problematic. Noir is more a matter of style than a matter of story, a way of orchestrating light and shadow to provoke a disturbed, subjective response to a sociologically attuned depiction of criminal activity. Ellroy writes historical romances set in a Los Angeles culturally remembered as noir in crime fiction, music and movies. How, considering the preponderance of narratives linking 1950s L.A. to crime, can he imagine this time and place differently?

Ellroy’s choice of subject matter, and his approach to it, are shaped by his having grown up in Los Angeles, as opposed to coming to it as an outsider. In My Dark Places he talks about how media and gossip shaped his perceptions of his immediate surroundings. The Badge, Jack Webb’s non-fiction literary addendum to his hit T.V. show Dragnet, hipped him to a secret world where sex-crazed psychopathis like Stephen Nash and Donald K. Bashor prowled the streets looking for vulnerable citizens to violate. Connections between hyper-adrenalized male alienation and inexplicable violence were reinforced in sensationalistic daily papers like The Herald Express, a channel used (presumably) by the Black Dahlia killer to taunt the authorities. Ellroy also discovered the movie colony’s clandestinely cloistered world through his father’s tall tales of erotic dalliances with Rita Hayworth (which are entirely plausible, as it turns out) and exposure to gossip-filled tabloids like Tattler, Whisper, Hush-Hush and, of course, Confidential. The L.A. set detective novels of Ross Macdonald and Raymond Chandler filled out these narratives were rife with forensic detail and boasted a trajectory towards justice. Ellroy’s formative years were shaped by a mediated sense L.A. defined by sin and criminality.

L.A. noir’s literary and cinematic legacy, in its classic period, didn’t use crime so much as its subject but as a consequence. Many of the city’s Depression era intellectuals (most notably, The Nation’s Carrey McWilliams) were recent immigrants who were stupefied by how the planned gentrification of the city’s residential developments ( surrounded by citrus ranches over in the county) stymied the rise of working class, Tammany style ward politics and Progressive calls for governmental reform. The dominant class Midwesterners resisted forming an indigenous style to California living, preferring to transport their lifestyle of Victorian gingerbread architecture, evangelical Protestantism and populist politics with them. Meanwhile, working class neighborhoods northeast of downtown faced erasure and neglect in what cultural historian Norman Klein has called an erased history of class conflict. Boosterism favored development and rebirth while the “noirista” critique called attention to the precariousness of the built environment. The collapse of a movie set depicting the battle of Waterloo in Nathanael West’s The Day of the Locust serves as this concept’s most prominent metaphor. Noir’s variation of the political dialectic comes not from revolution but entropy. Struck by what Los Angeles wasn’t, much of the punditry began predicting an apocalypse of various speeds as an effect of the city’s peculiarities.

L.A.’s original noiristas (Most notably Raymond Chandler and James M. Cain) tended to depict crime as a consequence of long term decay or betrayal. Those who grew up in the shadows of noir, such as Chinatown scribe Robert Towne and Ellroy, see corruption in the origin of the city itself, rather than as an after effect. That notion lies in the Calvinist horrors present in the more authoritarian police dramas (and authoritarian noirs like T-Men and Walk a Crooked Mile) and salacious news coverage of the Cold War. It’s not a projection of what L.A. should be but isn’t, but an acceptance of the culture as is because there was no alternative. In City of Quartz Mike Davis’ complains that Ellroy’s paranoiac density erases noir’s progressive legacy, leaving us in a world in which, “there is no light left to cast shadows and evil becomes a forensic banality.” That critique misses the point. He is offering a counter-progressive update to noir’s sunshine and nighttime dialectic that titillates the viewer while scolding the sin.

While we’re on the subject of the left wing perspective on L.A. exceptionalism, Widespread Panic’s two large sections document, and critique, changes in modern progressive thought in the arts in Post WWII America. “Pervdog” surveys ruined communist collaborators following the Red Scare and the realization of Stalin’s totalitarian horrors (as exemplified in the murder of theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold). All but one member of a party cell tied to Ruth Horvath’s murder snitch to the authorities, and, in another betrayal of his stated code (“I won’t work with reds”), Freddy allies himself to Connie, the last stalwart because their bond with Ruth transcends ideology. in “Gonesville”, Ellroy skewers the Stanislovskian derived process of method acting. Its insistence on using (caps his) MOTIVATION!!! as a basis for authenticity develops, in the form of real life director Nicholas Ray, into a cult hell bent on existentially glorifying serial killer Caryl Chessman. Again, the motivation is personal. Ray’s growing influence over star James Dean, Otash’s shakedown protege, inflames the detective’s anger, as does his infatuation with Lois Nettleton, who seduces Freddy in seeking justice for her ex-roommate, one of Chessman’s victims. As we saw in This Storm, political action stems from his characters’ desire for elemental human connection and a tested, and often betrayed, faith in individual loyalty.

Grant, I’ve always been struck by how public intellectuals who write think pieces struggle with the transfiguration of political ideas in forms tied to artistic traditions. They tend to read characters as symbolic renderings of abstract ideas or stand-ins for real life people or events. Ellroy’s characters, embodying a symbiotic fusion of contradictory ideas within forms confuses both his critics and some of his fans of late. How do you see Ellroy functioning as a modern public intellectual?

Grant: around the time Davis was making his rep, Steve Erickson (as much an L. A. fantasist as Davis is an L. A. historian) wrote of attending a conference called “L. A.: Dream City or Doom City?” (The title echoes “Sunshine or Noir?,” the first chapter title of Davis’ City of Quartz, and I suspect him of organizing it.) Erickson noted that the title proposes an either-or choice, where he felt that the two are always bound together; the ideals of L. A. as Utopia require a countervision of Dystopia, with the two not undercutting but reinforcing each other. In Widespread Panic, Ellroy recognizes both visions as bullshit, just as American Tabloid torches both the legend of Kennedy’s Camelot and the all-powerful Mafia. Here, as in Tabloid, he goes to the source of the opposition and shows us how it’s made: how the Bad and the Beautiful of Hollywood were manufactured for consumption, and in just as much lived detail. (Ellroy remains one of our great writers of how people do stuff.) That’s why Otash is the perfect Virgil for this underworld: build up reputations or tear them down (or build them up so they could be torn down), he’s ready to do any of it. Considerably unlike Ellroy, Davis is a hardcore leftist, and as such, has always defined himself as in opposition to something–the Right, the Establishment, usually Capitalism. Ellroy has never been interested in opposing any kind of ideology; he has always built his own fictional world on his own terms (drawn, as you’ve said, from Confidential, The Badge, and 40s/50s Hollywood) and he’s only gotten more confident about this with age.

We’re all fools, brother, and we’re all sinners. We’re all on that razor’s edge between sin and atonement. That’s all of us. That’s the human condition: we ate the apple, brother, and that’s that. That is the tragic journey of all human beings. Human beings change; that is my moral obligation as a novelist. It is to portray that moment of flux, where people start out simple, heedless, feckless, and move, however tenuously and ambiguously, to the other side. (Ellroy)

Ellroy’s world made our world, and its morality, as ever, remains foreign to the modern progressive sensibility; there is no sense of an inborn equality, no original innocence (see above), and no sympathy extended towards those on the low end of the social order. Instead, there is a harsh and bracing judgment on personal action, especially on the exercise of power; the word rectitude crops up a lot in Ellroy’s work. He’s always written about the powerful rather than the victims, those defined by their action rather than being-acted-upon (which, y’know, defines drama), but beginning with Blood’s a Rover, he’s written more and more about that “flux,” that movement towards grace, and it’s been thrilling to see how that journey takes his characters across borders of gender, sexuality, race, and politics. What distinguishes Otash is how he never took that journey in his life, and he’s only starting it afterwards. (Again, Otash witnesses the characters who are on the journey, but doesn’t understand them.) For now, Purgatory is exactly where he belongs, and none of Ellroy’s other characters can keep him company there.

In the Ellrouevre, Widespread Panic is a necessary anomaly. The novella form suits Otash; he’s not a character who can or should sustain a longer narrative. (It took two entire novels to tell the epic battle of Dudley Smith vs. Ed Exley.) This lacks the romance and sweep of the historical novels because Otash doesn’t have a consciousness suited to romance or history; but that lack is Widespread Panic’s most moving subject. John, you mentioned The Day of the Locust, but another touchstone here is West’s Miss Lonelyhearts, nastier, shorter, and more brutal than Day, and telling much the same story about the prewar media and the Big City that Ellroy does about the postwar versions. There’s the same sense of a world where all that is solid has melted not into air or even dollars, but attention, as measured in the circulation figures (now, of course, in clicks); the same rise of the most transactional and the most lacking in conviction; and the same bitterness in the absence of any real human connection. (That bitterness is another Shostakovichian aspect of Widespread Panic.) Ellroy’s moral universe is a long way from convention, but it is moral; Otash lurking in Purgatory serves as a kind of background to all Ellroy’s other works, a picture of absence that makes the other presences stronger. Here, distinct from his gallery of rogues, killers, Quakers, criminals, and dreamers, is his true Man Without Qualities, with no love and no loyalties, without even narrative, only hype. He may be Ellroy’s most contemporary and realistic creation, and that scares the shit out of me.