You know, I don’t do it because. (Jasper Johns)

The surfaces claimed my attention first: richly textured, sometimes with newspaper underneath and words occasionally showing through; sometimes wild splotches and drips of oil paint layered over each other to an incredible density even when flat; sometimes nearly monochromatic so texture was all there was; sometimes covered in “sculpmetal” so an ordinary object, like a flashlight, looked like a microscopic picture of metallic skin. Even more than the incredibly dense oils of the nineteenth century or Monet’s fogs, this was art that wanted to be touched, that had a surface as complex as that of humans. Seeing Jasper Johns’ paintings made me start painting; I admire and love the work of other artists but Johns made me say That. That’s what I want to do.

Johns will take the same work and reproduce it in a variety of surfaces. His (American) Flag, the one that kickstarted his career in 1955, began as encaustic mixed with newspaper, and Johns specifically chose the medium of encaustic for its distinct surfaces. (Encaustics are hot waxes; since they solidify almost instantly, they allow the track of each brushstroke to remain visible without any smearing.) He went on to paint the same image (sometimes updating it from 48 to 50 stars) in gray, in white, in green, next to a panel of orange, in acrylics, in oils, repeated three times on smaller stacked canvases; in lithographs, in pencil, in ink on plastic, and in false colors so that the red-white-blue surface only appears as an afterimage for the eye. He has not painted the same thing; he has allowed the same object to recur in a different series of surfaces.

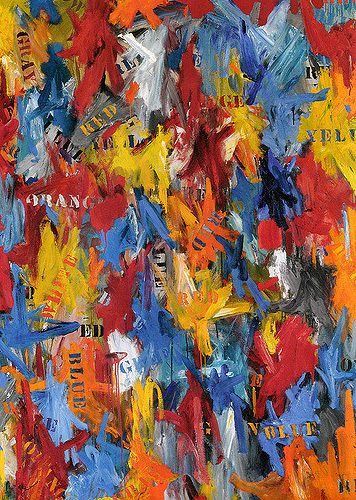

Once those surfaces came into being, they started attracting objects that stuck to them: chairs, words (often the names of colors), newspapers, casts of arms and legs, spoons and forks, tape measures and rulers, thermometers, brooms, string. Sometimes the objects stayed on the surface, sometimes they began to disappear into the surface, sometimes they did both at once. All the action and energy happens on the picture plane, along the axis of viewing; unlike Jackson Pollock’s work, where the layering is distinct and visible and creates the sense of a deep field of energy seen through a canvas-sized window (“bright weather, neon thunderstorms and the like,” Kurt Vonnegut said), everything that’s happening in a Johns painting happens right in front of us, all the push and pull, the emergence and absorption, right there on the picture plane. In False Start, the colors, their names, and the color of the names all compete to be literally on top and we see the moment of maximum tension in the struggle. (In another reworking, Johns later took out the color and kept all the activity for the grayscale Jubilee.) Anything behind it would be unnecessary.

“Surface” gets a bad reputation in our critical vocabulary. Depths, underlying meanings, what’s behind this, three-dimensional are all compliments; superficial, shallow, nothing past the surface, two-dimensional are all insults. (Johns is a big fan of Ludwig Wittgenstein and I’m following his rule: “the meaning of a word is its use in the language.”) Our surface, though, is our interface between ourselves and the world. To shift value away from surface and appearance means to shift our attention to our interior, to separate our self from the rest of the world. It goes beyond criticism to a fundamental assumption of our culture that’s been in place since at least Plato: the split between mind and body, and the devaluing of the latter. There may be no more pervasively stupid idea in our culture than the location of the soul as something “deep inside” the body, or even (come on) not in the body at all, instead of something that permeates the whole body, including the skin. (The first words of the first draft of Genesis describes Yahweh instilling clay with His nefesh, his breath/spirit, and making clay alive. That gets it right.) The surface sensuality of Johns’ paintings make them as meant for touch as we are. (There need to be a few Johns in every museum that the patrons are allowed to touch, like a petting zoo.)

“Surface” gets a bad reputation in our critical vocabulary. Depths, underlying meanings, what’s behind this, three-dimensional are all compliments; superficial, shallow, nothing past the surface, two-dimensional are all insults. (Johns is a big fan of Ludwig Wittgenstein and I’m following his rule: “the meaning of a word is its use in the language.”) Our surface, though, is our interface between ourselves and the world. To shift value away from surface and appearance means to shift our attention to our interior, to separate our self from the rest of the world. It goes beyond criticism to a fundamental assumption of our culture that’s been in place since at least Plato: the split between mind and body, and the devaluing of the latter. There may be no more pervasively stupid idea in our culture than the location of the soul as something “deep inside” the body, or even (come on) not in the body at all, instead of something that permeates the whole body, including the skin. (The first words of the first draft of Genesis describes Yahweh instilling clay with His nefesh, his breath/spirit, and making clay alive. That gets it right.) The surface sensuality of Johns’ paintings make them as meant for touch as we are. (There need to be a few Johns in every museum that the patrons are allowed to touch, like a petting zoo.)

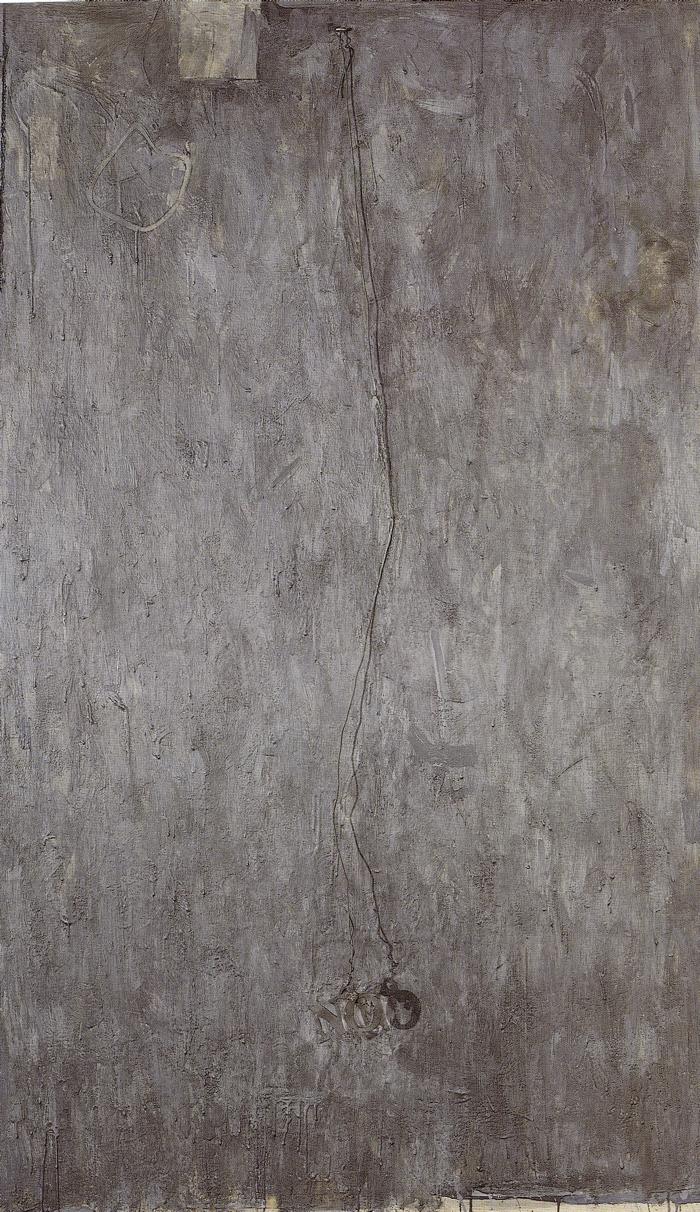

He gets that sensuality by working the shit outta those surfaces. Nothing there is by accident (he said once that “it sometimes happens that something unexpected occurs–the paint may run–but then I see that it has happened, and I have the choice to paint it again or not. And if I don’t, then the appearance of the element is no accident.”) Johns paints and repaints his surfaces; a recurring technique is to start with colors and then paint them over with gray until only a hint remains, sometimes with an exposed streak of original color. (Philip Guston also did this for a while.) He also carefully organizes what look like blank, monochromatic surfaces: his paintings Near the Lagoon and In Memory of My Feelings–Frank O’Hara have quite specific, deliberately overpainted structures and images.¹ There’s something almost geological about his approach, all this work and layering when all that’s visible will be the surface stratum. Like geology, though, it becomes something more than beautiful, and it will last.

A greatness of Johns and a bafflement of critics is that there’s nothing past the surface, nothing but the surface.² So many critical writings about Johns and especially conversations with him are about trying to find that meaning behind the surface, and he never gives one, never even considers one. Michael Crichton’s conversation that begins his book on Johns (called, intriguingly, Jasper Johns)³ is archetypal:

Working on one print, he drew a spoon and a wire. He worked on the spoon handle for some time. However, after one of his judicious pauses, he changed it considerably. The handle was now different, but as far as I could tell, it was not different in any way that mattered. There was nothing to do but ask.

“Why did you make that change?”

“Because I did.” His tone implied great reasonableness, as if that were the only possible answer.

I persisted: “But what did you see?”

“I saw that it should be changed.”

Since I wasn’t getting anywhere, I tried another approach. “Well, if you changed it, what was wrong with it before?”

“Nothing. I tend to think one thing is as good as another.”

“Then why change it?”

By now he was getting exasperated with me. He sighed. There was a long pause. “Well,” he said finally, “I may change it again.”

“Why?”

“Well, I won’t know until I do it.”

What’s implied in so much thinking about art–that the artist has an image or a vision or an idea and then realizes it in the work–has no place with Johns. There is no underlying thought; it all happens on the surface at the moment of painting. He isn’t (and he carefully distinguishes himself) from his 1950s contemporaries, the action painters. They sought to make their paintings the results of their spontaneous gestures, of an underlying psychology expressed in that gesture, with Pollock the exemplar of this group. Johns isn’t about the spontaneous gesture but about the process of thought, and that process doesn’t take place only in his mind but in his hands as well, in the process of painting. He carefully paints and revises, and if he has plans, they keep changing as he works. Johns collapses the distinction between thinking and acting (“I won’t know until I do it,”) between the thinking subject (the painter) and the resulting object (the painting); his works do not result from thought, they are thought, and what we see is one frame of it at the moment he stops–or maybe it’s better to say the moment he begins the next one.

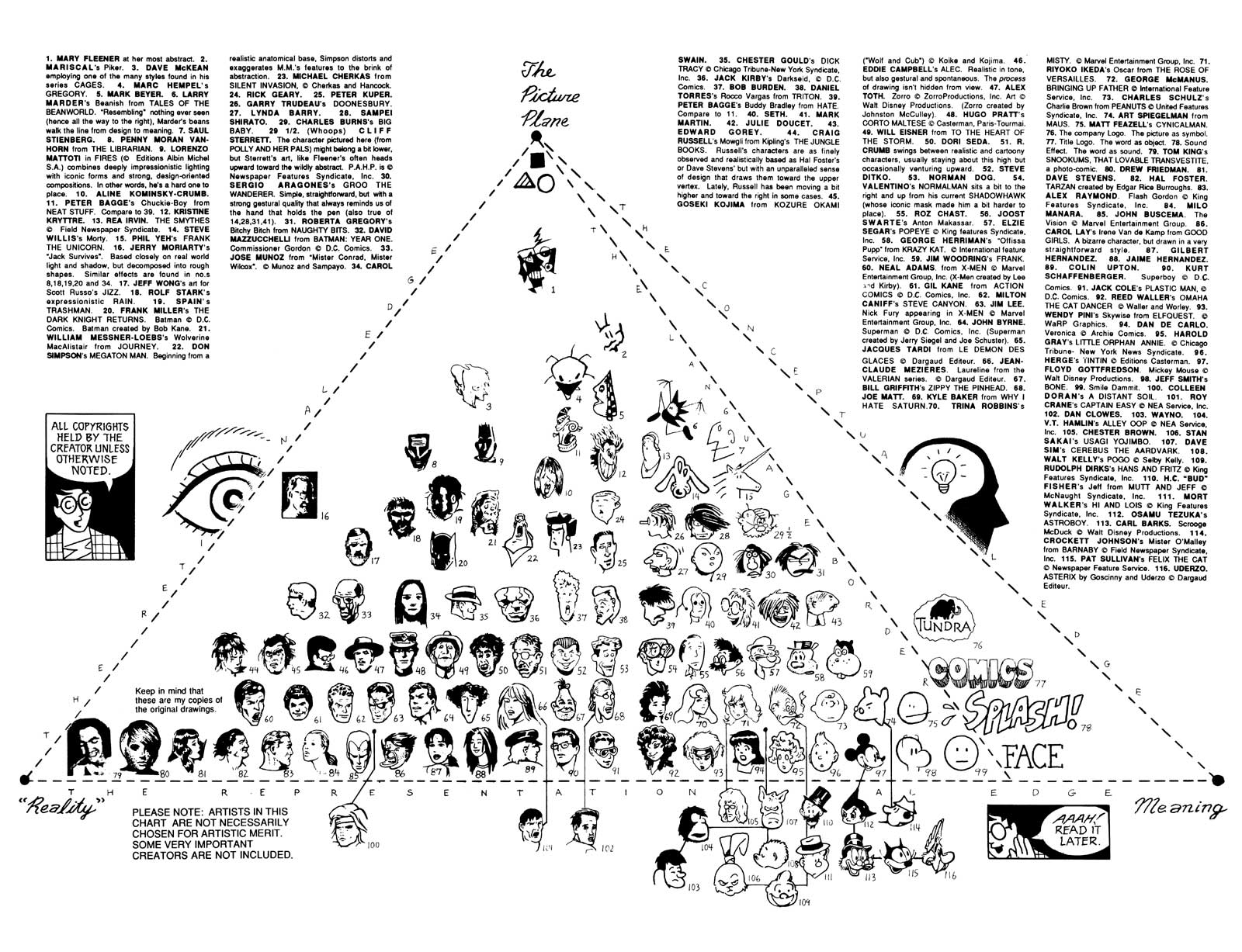

Johns painted things, especially through to the 1980s, that are common cultural property: maps, flags, targets, numbers, letters, words. In other words, they’re icons–even if he paints a flag in monochrome we can recognize it as a flag. Scott McCloud, in Understanding Comics, created one of the best art theories about icons. McCloud began with a typical spectrum in art: from the realism of a photograph to pure abstraction. He added a third category and created a triangle: the icon. We do not see 🙂 as two dots and a semicircle inside a circle; we see a face, and that’s what makes it an icon. You need no skill to draw 🙂 because its effect is linguistic, not pictorial. It’s not abstraction–it’s interchangeable with “smile” and a Pollock abstraction is not interchangeable with any word. (You can try assigning a word to a Pollock, but you won’t get agreement.) McCloud uses this triangle to map out a comprehensive taxonomy of comic styles:

The trend of a lot of modernist painting, beginning with Cézanne, is to take material from the realistic (lower left) corner and push it towards abstraction; Johns takes material that’s firmly in the 🙂 corner and pushes it away from there. He takes images and objects that are part of our everyday thought and makes them suddenly alien, far more than Andy Warhol ever did with his soup cans. (Elizabeth Murray said that “people forgot how to work with all the material that Johns gave us.”) It’s the estrangement-effect (остранение) that Viktor Shklovsky cited as the basis of all art (h/t to pico for bringing this to my attention): “the translation of the familiar into a medium which estranges (or ‘defamiliarizes,’) as it’s sometimes translated) the thing into artistic tropes” and thus make us see the world differently.

The trend of a lot of modernist painting, beginning with Cézanne, is to take material from the realistic (lower left) corner and push it towards abstraction; Johns takes material that’s firmly in the 🙂 corner and pushes it away from there. He takes images and objects that are part of our everyday thought and makes them suddenly alien, far more than Andy Warhol ever did with his soup cans. (Elizabeth Murray said that “people forgot how to work with all the material that Johns gave us.”) It’s the estrangement-effect (остранение) that Viktor Shklovsky cited as the basis of all art (h/t to pico for bringing this to my attention): “the translation of the familiar into a medium which estranges (or ‘defamiliarizes,’) as it’s sometimes translated) the thing into artistic tropes” and thus make us see the world differently.

Johns differs from his contemporary (and onetime lover) Robert Rauschenberg on this point. Rauschenberg made his assemblages (“Combines”) of paint and objects in the 1950s, at the same time Johns was painting his icons. The combines are messier, denser, more random in their presentation, and less iconic in their materials. In the 1960s, their paths (personal and artistic) diverged; Robert Hughes makes a good case that Rauschenberg, in his silkscreened canvases, began to use images rather than objects as artistic material. Rauschenberg’s works are more particular than Johns’; they have the feel of a personality, whereas Johns explicitly sought to get away from personality, creating something that approaches the stability of scientific objects.

The Scientist

Nothing can be deduced from anything else; nothing can be reduced to anything else; anything can be allied with anything else. (Bruno Latour)

Writing on Johns, Crichton saw something of the approach of science (I try to avoid the term “scientific method” because I’ve never seen just one, and as Latour sez, science makes a great noun but a lousy adjective and worse adverb) in his work: the sequence Thomas Kuhn identified in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions of working under a style (a paradigm), pursuing it as far as he could in as many ways as he could, until it reaches an untenable point of contradiction, and then abandoning the style and working in a new one. (Crichton wrote the first edition of Jasper Johns during Johns’ “hatch mark” style of the 1970s, something Johns gave up long before the second edition.)

There’s something nearly rigorous about the way Johns approaches his material, something very much like the scientific practice of replication: if something works, then try it again under different circumstances to see if it still works there. Science isn’t universal, it approximates universality; and it does so not by reason but by repeated success. We can talk about the universality of Maxwell’s equations all we want but you still need wires, transmitters, and receivers to see electricity work. Johns often makes sketches of his paintings after the paintings; they are not studies but something closer to repeated demonstrations of a theory.

Here, I’m ripping off a lot of concepts from Latour, with that of the alliance perhaps the most useful. Scientific theories, in his terms, are not deductions or explanations; they are alliances between two different things. Newton’s laws don’t explain gravity, they say nothing about why, they tell you what will happen; and they’ve been demonstrated millions of times over hundreds of years. (Trust them.) “Reality,” in this language, isn’t a matter of either-or but of how much, and it’s not a pre-existing thing but the result of a process. The work of science takes some alliances and strengthens them until they become facts, and allows others to weaken and fall away until they become artifacts, noise, or hallucinations.

Johns’ flags are in the former category; he’s repeated them so many times that when he includes them in a more recent painting, it refers to his own work and not to the American flag. They have the status of fact; they can be used as part of another work without question. (The power of science, and at the same time its greatest weakness, is that it’s most successful when we take it for granted.) He has quite a few things in the abandoned-artifact category too: imagery of a stone wall he saw in Harlem got repeated in some paintings in the late 1970s but never caught and held in the work. Johns has inspirations like any of us, but what makes him distinct is that work of science, of continually experimenting with the same elements to see if they can endure. Maybe that’s why his paintings are so spare: he only includes the things that will last.

Johns’ paintings explain nothing. They present surfaces that attract and ally themselves with meaning. In the way that Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control feels like the pre-theoretical moment of science, Johns’ paintings are scientific theories at the moment they begin, at the moment someone writes an equation and wonders if it can apply to anything, at the moment someone draws what they see through a microscope and wonders is this real? There’s a feeling in the best Johns paintings that he’s stripped the elements down to the most essential, and they’re often stripped down further into the prints. Like theory, he provides the fewest elements because that allows the work to have the broadest application. (One way of stating Occam’s Razor, the one I always use: claim no more than you need to.) That’s the difference between Rauschenberg and Johns: the Combines are expressions rather than theories. They provide too many meanings on their own; any reading can be contradicted. Johns goes the other way, attracting meanings.

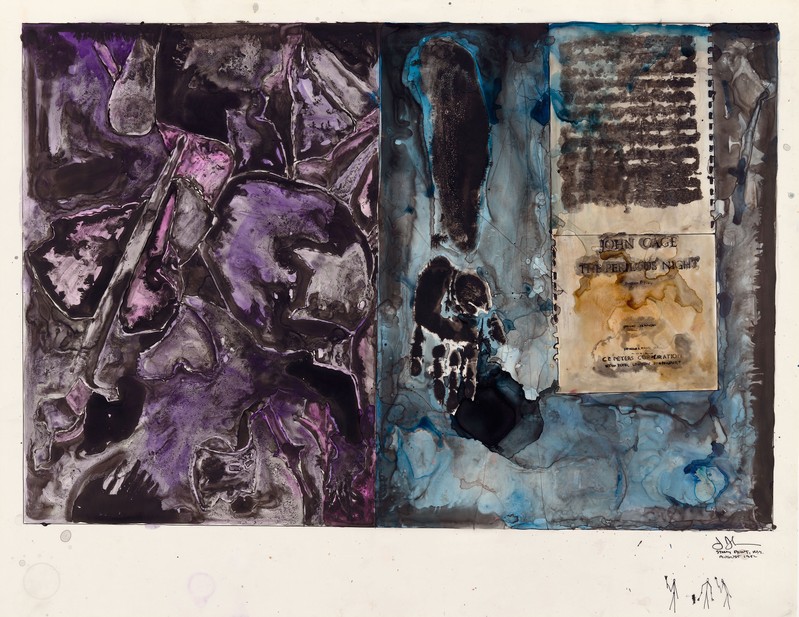

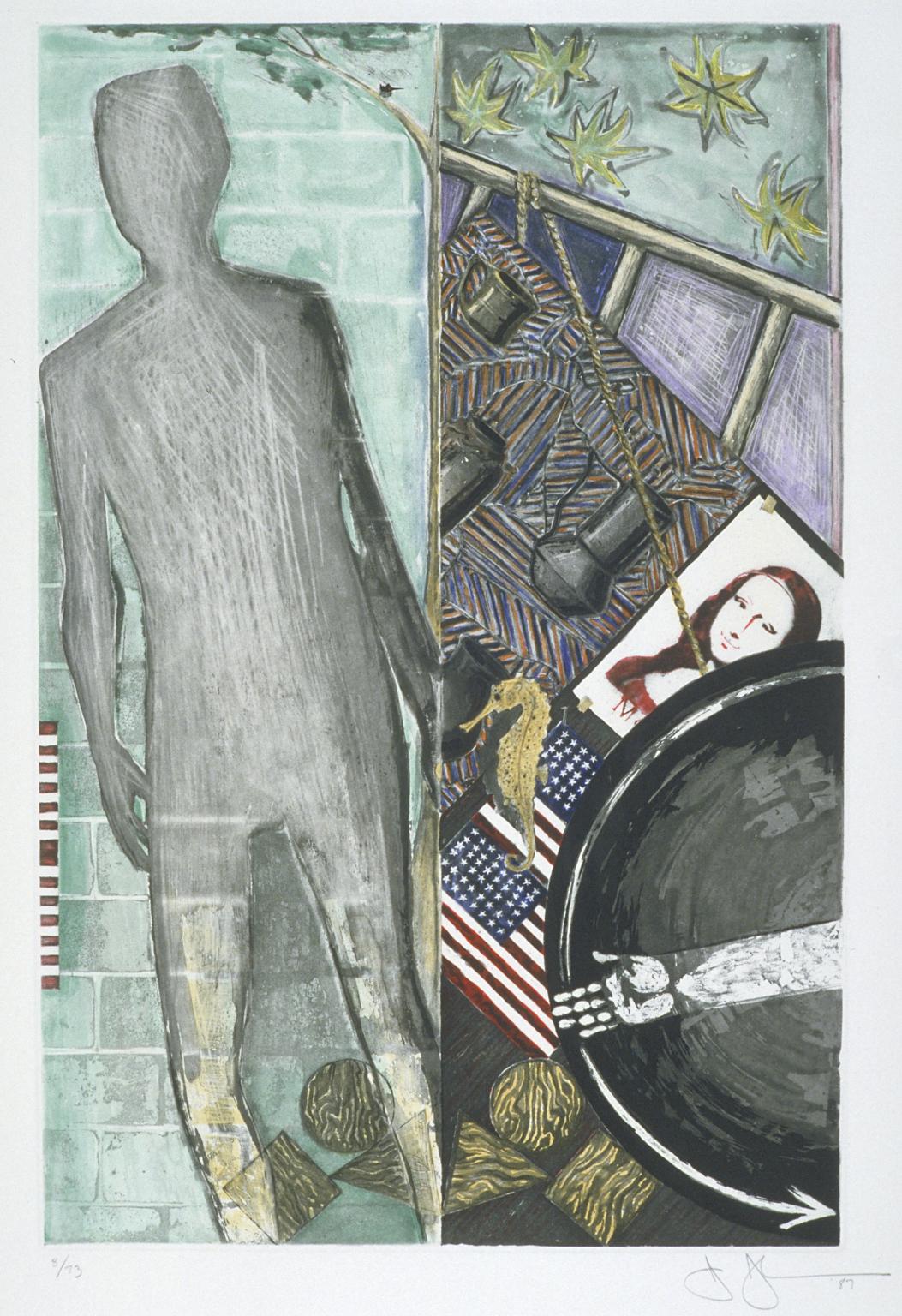

The science-ish progress of Johns’ work can be seen when looking at his career as a whole. (Like Cindy Sherman or Walt Whitman, his works are best seen as parts of a single, lifelong art project.) He started with single images (the target and the flag) and then began replicating them in different contexts and media. After than, he began bringing in new objects/images and creating alliances between them: the hand, the “device circle” (a piece of wood that smeared out a circle of paint), the spoons and forks, the stencils. (About the stencils, his dealer Leo Castelli asked “do you use these letter types because you like them or because that’s how the stencils come?” He replied “But that’s what I like about them, that they come that way.”) Big works like Diver, Perilous Night, and According to What ally multiple and disparate things, and it’s a mistake to try and find connections between them. (According to what law? According to what equation?) Finding connections assumes the connections are there to be found. Johns asserts connections, he doesn’t represent them. These aren’t laws yet, any more than the track of a planet through the sky, the arc of a cannonball, and the weight of a person have any connection before Newton’s conception of gravity. The connections–the stability–will come later, as Johns will strike multiple prints, repaint, re-stencil, re-draw them, and some parts of them will achieve stability and some won’t. He does the scientific work of calling these connections into Being, and then stabilizing them as far as he can. He continues under one paradigm of creation until it’s exhausted, and then breaks off and starts a new and radically different one.

The value of a theory isn’t in how it’s made, but whether or not it lasts. Johns’ method of alliance and repetition and his use of everyday, recognizable icons move his paintings away from the immediate spritzing of psychology of the Abstract Expressionists. Pollock’s paintings are incredibly difficult to fake: try all you want, you can’t imitate the exact motion of his arm as he flings the paint around. With Johns, anyone could do it–and that’s praise. (For all his vast talent, it’s his commitment that’s made his work last. Part of that commitment was not self-destructing like Pollock.) It’s a necessary part of the work, it’s what gives his paintings the feel of science. Take a single alliance, diligently repeat it, varying it a little each time, and you have a Johns painting or a scientific fact. The only difference is the scale.

At the end of Jasper Johns, Crichton tosses out a suggestion: Johns doesn’t like to wear glasses because he always notices the frames, and Crichton observes that after wearing glasses for a while, most of us don’t notice the frames because our brains edit them out. He speculates that Johns’ brain might work differently and not do that. I’ll take this a little farther: Johns might lack an ability to make connections between things that most of us do, and take for granted. He can only connect through painting, through actually making the connections visible on his surfaces. He actively builds up connections between disparate objects, creating the beginnings of theories from the material of our everyday lives.

Literature Without Narrative

It’s almost as though he has discovered a language; or, better, has heard of a language: heard about some of its vocabulary, its grammar and its sounds, and before he can comprehend it, starts using this set of unformed tools to narrate the most important event of his life. (Michael Pisaro, not writing about Johns)

In the 1980s, Johns shifted from the “hatch mark” style, and it hasn’t come back except in referential fragments. His paintings began to get more cluttered, with more things coming into them, both as image and object. (Sometimes, as in the trick image of the nail pinning the handkerchief in Perilous Night, in some ambiguous space between the two.) He hasn’t done anything on the scale of According to What since then; there’s the feeling in these canvases that they’re as big as they need to be. He paints fragments that are somehow enigmatic and accessible: pottery, his body, shapes, the Mona Lisa, a string hanging in front of the canvas. He hasn’t abandoned the scientific approach; he has overlaid it with, perhaps allied it to a literary one.

As any regular reader ‘round here knows, the most excellent Drunk Napoleon has been exploring the differences between literary and dramatic approaches to storytelling in a variety of media. He has offered this definition of the literary approach: “story beats, connected by harmony and contrast.” Whereas a drama proceeds by necessity, literary works get their power from juxtaposition, for example by cutting between scenes of different characters doing different things that relate not on the level of plot but of character or theme. (We both agree that Mad Men is television’s highest development of this style.) Literary works don’t operate on the level of the essential dramatic question of “what happens next?” but on more reflective questions, often questions that have a “why?” in there somewhere.

As any regular reader ‘round here knows, the most excellent Drunk Napoleon has been exploring the differences between literary and dramatic approaches to storytelling in a variety of media. He has offered this definition of the literary approach: “story beats, connected by harmony and contrast.” Whereas a drama proceeds by necessity, literary works get their power from juxtaposition, for example by cutting between scenes of different characters doing different things that relate not on the level of plot but of character or theme. (We both agree that Mad Men is television’s highest development of this style.) Literary works don’t operate on the level of the essential dramatic question of “what happens next?” but on more reflective questions, often questions that have a “why?” in there somewhere.

Johns presents those beats with harmony and contrast, and the advantage of painting is that he doesn’t have to slog through a whole bunch of story to get there. With storytelling, you need some degree of plausibility to get from moment to moment; without that plausibility, you move into the world of Surrealism. Although that’s not in and of itself a bad thing, it’s a reminder that literature (and film, and television, and theater) are still linear experiences: the progression from first scene to last, from first page to last, still unavoidably matters. With books and DVDs, without question, we can jump around in time with rereading and reviewing, but our first experience is almost always in sequence. Johns has the advantage of working on a surface where we only see everything at once. We can’t help but see, in Regrets, the outbreak of color in contrast to the surface of gray; or, in his series The Seasons, the tilt of his body looming over everything; or, in his paintings of the 2000s, a catenary string hanging in front of the painting, somehow a signifier of exhaustion. In all these cases, since there’s no sequence, there’s no surprise either. Johns’ earlier style of stripping down his paintings to just the essential icons is prelude to this: here he removes the narrative from literature, the beat-by-beat connections, and shows us nothing but what is necessary with the most naked emotional charge.

Icons are so embedded in our culture that their meanings are stable; they feel like natural law. Literary meanings are more fluid and specific; they exist in a web of other meanings. (The difference between literary and scientific meanings is one of degree rather than kind.) Johns only began this more literary approach after he’d built up enough images and references to have that web. When the painted (48-star) flag appears in The Seasons, it calls up Johns’ own history and some of the modern history of painting, just as the Mona Lisa calls up its past. (The four paintings of The Seasons and their titles–you can guess what they are–also bring in associations.) The score of John Cage’s Perilous Night appearing in Johns’ painting calls up Cage’s career, and Johns’ friendship with him. They’re what make literature so much about the particularity of a life. This is the major break of the 1980s-and-beyond work: it could only be done by Johns.

Those associations keep multiplying. (I haven’t mentioned the pottery Johns collects or the details of his studio in the Caribbean islands that show up in his paintings.) Many of the paintings of this period have specific origins in other paintings, well-disguised. Near the Lagoon uses as its background shapes from Degas’ reconstruction of Manet’s painting The Execution of Maximilian (as if that weren’t obvious); Regrets takes its structure from a photograph of Francis Bacon. (This article dissects the meanings and the possible references to Rauschenberg there.) It’s not necessary to know these things to enjoy these paintings; the pleasures of the surface are still there–I found the outburst of color in Regrets so moving long before I ever read that article. Knowing about them, though, enhances the experience, whereas trying to read the underlying words of the newspapers in the 1950s paintings and work them into a reading (yes, I’ve seen people do this) is just plain silly. If these newer works are literature, then they benefit from a literary reading.

In some ways, this work of Johns resembles Rauschenberg’s from thirty years earlier, and also the boxes of Joseph Cornell. All three artists assembled disparate objects into a surface or space. With Rauschenberg and Cornell, though, every work feels different from another, each one a thing by itself. Put all of their work together and you have a collection, but with Johns you have a series. His paintings are sparer, with fewer elements, and those elements have been repeated enough so that there’s a history to them. That’s where Johns’ history of science comes into play. He created a language with his elements: some of those elements are older, more stable; some are new and pick up meanings from the old. Just as in science, the journey is necessary, because you need a language before you can have a literature.

The Future

The rocks there etched with pictographs perhaps a thousand years old. The men who drew them hunters like himself. Of them there was no other trace. (Cormac McCarthy, No Country for Old Men)

Crichton concludes his study of Johns with “The form his work takes is a particularly modern, twentieth-century form. But its power is as old as Paleolithic cave art,” which is ⅞ right. The power of Johns is to become as old as cave art. We don’t know what the purpose of cave art is, although that doesn’t stop him, me, Alexander Marshack, and a whole lotta art historians and anthropologists from speculating. The art of the long past, drawings on caves, pictographs on rocks, has something compelling about it, a kind of purity, precisely because we have to speculate on its purpose and context. Almost all art has a literary dimension to it, a way in which it’s embedded in a history of references and other artworks, and most art criticism seeks to explain this embedding–one more way in which most contemporary criticism takes place in a literary mode. To see these images that are from a time before writing, a time so far past that “meaning” doesn’t have the same meaning, is the fiercest dislocation, and that’s what we can see in Johns.

All of Johns’ works take things and rip them out of context, and create new contexts for them, a private language. The ripping-out may be the most powerful effect, though, the one that will last past his life. Words get isolated from sentences; icons get isolated from the everyday world; meanings get stripped of narrative and stand as naked objects; structures get overpainted until they’re barely visible. In his own process of making the paintings, he layers them until the original meanings are buried. What Johns’ paintings have in common with cave art isn’t their purpose (at least, I’m not sure that it’s their purpose); it’s that Johns’ art looks as old as cave art. He makes what is now look like it’s of a past that’s an alien world.

As time passes, the monumental nature of Johns’ work becomes clearer. His paintings are not documents; they do not reveal something else behind them. (I’m swiping the distinction between document and monument from Michel Foucault.) Reading art as a document invariably means reading it in some kind of historical context and imputing motives to the artist, but almost a definition of good art is art that outlasts its context. A straightforward and valuable question that often gets asked about art: “if the artist meant X, why doesn’t he/she just say X?” Johns has created things that, even if they come from what he meant, have a stability past that; his iconic paintings move away from being icons, which means they move away from our context. That’s the estrangement, not of meaning or image but of time, the most destructive force around. Johns’ paintings have already started to age into another world, faster than us. Stripping out so much context, he leaves only the monuments, there without any narrative, like a fossilized skeleton with everything around it–muscle, blood, feathers, skin, every other living thing, meaning, and society–gone.

That’s the true displacement of Johns; he makes us see what’s in the present as if we were looking at it in the future. He builds up new associations from these elements just as we do when we look at the past. All art (as opposed to propaganda) makes a claim on the eternal; all art is in some way a challenge to God’s time. Johns’ art is already in the future, and we won’t be. He’s a great and humbling artist because he reminds us of what time does, how little can last. One day, other eyes will look at our world, and whatever’s left will look to them like Johns’ paintings look to us.

¹This and several other insights about how Johns painted or printed his stuff come from the Art Institute of Chicago’s 2007-8 exhibit Jasper Johns: Gray; Kelly Keegan and Kristin Lister’s article “A Shifting Focus: Process and Detail in Tennyson and Near the Lagoon” was most helpful, and the interview with Johns was very funny. Overall, this was the best show ever of my most beloved museum. Organizing the work of a visual artist around something visual: how badass is that?

²A reflection of my love of Johns and interest (for good or for ill) that stops at surfaces: I keep very few things in any kind of storage, even in drawers or closets. Almost everything I use is out and available to be grabbed. I think the same way; nothing I’ve written has been anything but obvious.

³This difficult-to-find book is easily the best thing Crichton has ever written. It comes from his pre-Jurassic Park period (he revised it in 1994) when he was questioning different subjects rather than using them to stamp out thrillers. (The awkward but interesting Travels comes from this period as well.) Crichton applies a range of ideas from science in an attempt to understand the enigmatic Johns, and he achieves what criticism can do at its best: not dogma about how art should be interpreted, but opening a new way of seeing art. As much as Johns’ art, Crichton’s book feels like the beginning of a theory. After this, Crichton moved towards a sequence of “learn about something, write a cheap airport novel about it, then forget about it and learn something else” that kept him well-paid for the rest of his life. It’s superficial, and not in the good way.