When Gaspar Noé released his excruciatingly boring porno cum arthouse provocation Love in 2015, a lot of ink was spilled about its central conceit: that the whole ponderous thing was shot in 3D, allowing Noé to figuratively spew bodily fluids in the audience’s face. (It was probably only health and safety regulations that, thankfully, kept him from literally doing so.) Love was received as the latest mad gesture from an enfant terrible, but its 3D gimmick had plenty of precedent, dating back at least to 1969’s bafflingly successful The Stewardesses.

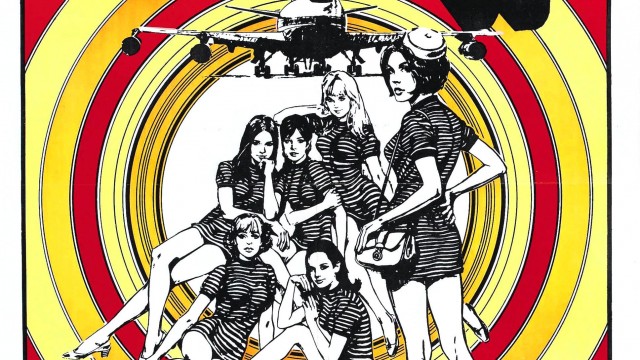

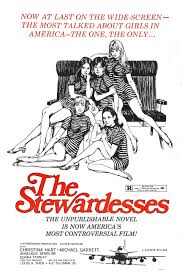

A low-budget soft-core that promised to “leap from the screen to your lap,” The Stewardesses 3D had an incredible run, grossing 250 times its budget and playing to entranced late-‘60s / early-’70s audiences for years, despite being, objectively speaking, the fucking worst.

I’m not sure exactly how “forgotten” this Forgotbuster is – its mildly comic standing as one of the most financially lucrative films of all time and a notable innovation in 3D technology probably assure some amount of familiarity, at least to film historians, future-tech enthusiasts, and drug-addled weirdos – but it doesn’t exactly get talked about much. This is probably related, at least in part, to how mind-bogglingly terrible it is. It really has to be seen to be believed, and even now that I’ve seen it, I’m not sure I believe it. Like one of its characters, I might’ve taken some bad acid and imagined the whole thing.

Written, directed, and produced by incomparably-named apparent auteur Al Silliman, Jr. (IMDB notes his credit “as Alf Silliman, Jr.”, which just increases the ridiculousness of the whole thing), The Stewardesses 3D occasionally lays on the plot but mostly sticks to the fucking.

For the most part, this is a wise decision, since the “plot” Silliman arrives at is a deeply uncomfortable one. Like most sexploitation, the narrative is a thin, skeletal frame to provide some justification for the nudity. As a genre rarity, however, it also features a woman who drops acid, gets naked, and makes out passionately with a lamp. (Did I mention The Stewardesses is deeply weird?)

Al/Alf Silliman was also known as “Allan Silliphant”, and best known for writing the story for MST3K favorite The Creeping Terror (“Is she really going out with him?”). Silliphant, whose brother Stirling (are you still with me?) had a successful screenwriting career, kind of parlayed the family name into something like fame and fortune, a jetstream that eventually carried him to The Stewardesses.

Phew. Anyway, the stewardesses of The Stewardesses are played by Christina Hart, Anita de Moulin, Paula Erikson, Kathy Ferrick, and more (including a young Monica Gayle, who would go on to star in the semi-well-known Switchblade Sisters and the, um, less-celebrated Dr. Dildo’s Secret).

We are introduced to them mid-flight on their very swank plane, part of the Trans-Pacific SPA fleet (a fiction that Silliman, hilariously, later made real by founding his own plane company – is there anything this guy can’t do?). They are dolled-up in the traditional attire of 1960s flight staff, or at least the traditional fantasy of such attire as imagined by dirty old men.

They’re landing in L.A. after a trip from Hawaii and have an evening to kill. In the next 12 hours or so, they will smoke a lot of weed, stand around inexplicably naked to stretch, attend some psychedelic rock band’s terrible concert (featuring an uncredited, very stoned Paul Shortino, later of Quiet Riot), and have a lot of grinding sex in various combinations.

All the while, the camera zooms in and out, clumsily mounting an attempt to get the most out of the 3D. It’s dizzying, and counter-intuitively unsexy despite the copious nudity. It’s hard to imagine anyone with the capacity to both keep their eyes in focus and masturbate during The Stewardesses, but I guess that’s a skill, like rubbing your stomach and patting your head, that takes practice.

The lamp sequence is the funniest and best part of The Stewardesses. One of our protagonists arrives at her parents’ house in L.A. to discover they’ve gone on a trip. “Maybe,” she considers out loud, “I’ll take a trip of my own … ON ACID.” And so she does.

Apparently because LSD either greatly increases desire or sharply reduces its user’s sense of the absurd to more manageable levels, she proceeds to writhe and grind while kissing a lamp that is made out of a statue of Alexander The Great’s head. No explanation is provided for any of this, and the scene goes on for a little over four minutes. Quick, trippy 3D flashes of Alexander The Great’s face are intercut with her fantasies and her nude, lustful form. It’s unclear how or why Silliman imagined this would be erotic. Instead, it alternates between hilarious and outright terrifying. Points for trying something new, I suppose.

Weird as it is, though, the Alexander-The-Great-head-statue-lamp-fucking business is ultimately a lot more pleasant than the narrative that takes hold for the film’s final minutes. In between the assorted couplings, experimentation with the wild world of lipstick lesbianism, and a bout of cockpit sex (a pun The Stewardesses, rather inexplicably, doesn’t employ), we follow one character who dreams of being an actress. By happenstance, and the demands of pornography plotting, one of the guys on the plane works in advertising, so she promptly works to connect with him.

And this is where The Stewardesses briefly turns into a horror movie. In their scene together, it’s revealed that the wealthy, apparently well-adjusted advertising agent is wrestling with some serious demons. He casually informs us, by way of explaining the industry’s dangers, that he was sexually traumatized himself by a male superior at the firm, going along with it presumably to advance his career.

After delivering this terrible, baldly homophobic, and completely out-of-nowhere monologue, he and the stewardess lie down for what we assume will be yet another long scene of 3D sex. Instead, he appears to attack her – implicitly, we are meant to understand that his own prior assault has damaged his sexuality, and this jarringly invoked story of gay workplace exploitation has made him an apparent rapist. To put it mildly, this is not a welcome plot pivot for The Stewardesses.

In tears, she recovers from this bit of inexplicable, utter nastiness, picks up a lamp (again – The Stewardesses really emphasizes lamps for some reason), and smashes his face in, before leaping to her death from 30 floors up.

We then smash-cut to Monica Gayle back on the flight, welcoming passengers aboard and introducing the flight crew (one of whose names she clearly blanks out on … and then forgets her own character’s name. Silliman apparently didn’t feel the need to reshoot this scene). Gayle’s welcoming smile and endearing tone stands in stark, deeply un-groovy contrast to the awfulness we literally just witnessed moments ago.

The plane takes off, and credits roll. The implication seems to be that these things will continue and repeat forever. We thought Silliman was offering a good-time romp, but it turns out The Stewardesses is an existential nightmare of eternal return.

How did audiences receive this at the time? It seems unlikely only hippies were populating the theater — and in fact, it seems unlikely hippies would’ve wanted to check this thing out at all, being too busy with the reefers and doses and humping of household objects, presumably.

This is a movie for titillated squares — it speaks to mainstream fascinations and anxieties. But it features so dark and bewildering an ending that the mind reels. After an hour and half of halting narrative, jettisoned as quickly as it starts in favor of good old fashioned porn, this is the closing storyline? Sexual assault, violent vengeance, and suicide? Is Silliman hinting at the darker aspects of the late ‘60s, some premonition of an Altamont-of-the-mind sneaking into his already quite bizarre piece of 3D garbage porn?

In any case, I certainly didn’t see it approaching. It has to be emphasized: all of that transpires over the course of the film’s final five minutes, as though someone said, “Hey, I’ve got an idea. It won’t take long; let’s just cut the footage in before the credits.” Who or why remains mysterious, and The Stewardesses moves from goofy curiosity to candy-colored nightmare-fuel.

Perhaps that’s why people don’t bring the film up too much. Audiences in 1969, on the other hand, were wild about The Stewardesses, which was cut down from an X to an R to capitalize on their voyeuristic enthusiasm, and repeatedly cut while it ran in theaters, with new footage being added and old scenes subtracted on the fly, so that audiences in different cities experienced different films depending on when they attended.

The marquee advertising emphasized this, rather cleverly: “Now with new footage you won’t believe!” and so forth. Part-provocation and part-dare, The Stewardesses grossed $25 million and became a sensation, the 14th top-grossing film of the last year of the ’60s.

Its development team went on to work on things like Jaws 3D, and, as mentioned, Silliman started an airline to cash in on Stewardesses-related fandom. These things have mostly faded with time, and now the film is both a relic and something of a weird legend.

If it’s remembered well by sexploitation fans, it’s probably for the 3D gimmick and not the inscrutably horrifying ending. I’m not sure what people will remember about it 47 additional years from now.

Speaking for myself, I’m guessing it’ll be the lamp-fucking.