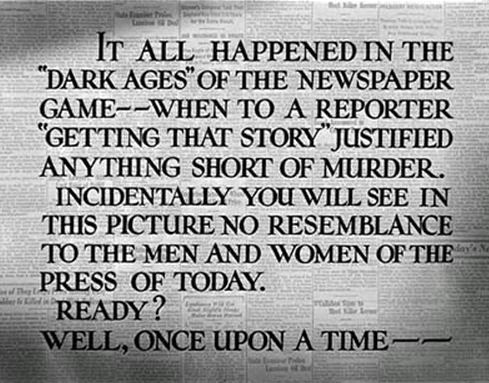

His Girl Friday treats the fourth estate as something between another branch of a corrupt government and an outright criminal organization. Appropriately the characters consort with both crooked officials and mobsters in their quest for a headline. The newsroom ranks are full of rouges drinking, smoking and cheating their way to a scoop. Director Howard Hawks plays up this notion in its opening card while attempting to placate the rogues themselves.

Hawks knows the conventional wisdom about picking a fight with people who buy ink by the barrel.

Adapted from the play The Front Page by Ben Hecht (previously filmed in 1931), Hawks famously switched the gender of ace reporter Hildy Johnson (Rosalind Russell) adding a new wrinkle to her conflict with her editor, Walter Burns (Cary Grant). That character is now Hildy’s ex-husband as well as her boss. When she arrives to tell him of her plans to quit the paper and leave that afternoon to marry another man and settle down and have his babies, Walter schemes to keep her from leaving. Whether he hates to lose her as a reporter or a companion is unclear. As we’ll come to learn, the differentiation may be academic to both Walter and Hildy.

Hildy’s new fiancé and Walter’s new competition is Bruce Baldwin (Ralph Bellamy), a milquetoast straight man to the world at large. Baldwin is out of his element as soon as Hildy leads him into the newsroom which is abuzz with Friday’s signature fast talkin’. Bellamy delivers first line with slow deliberation and hearing the way he lets pauses clings to his line is like witnessing him swallow a large lump of oatmeal. Bruce is doomed. The story and dialog only gain speed and poor Bruce will be swept away with the current.

Hildy’s timing is terrible for dreams of domesticity, perfect for awakening ambition. The afternoon she enters Walter’s office to quit him and the newspaper is also the eve of the execution of a meek immigrant (John Qualen). The case is a cause célèbre of the paper and a hot story to boot. As Walter’s attempts to get Hildy back on the beat (and Bruce in jail) intensify, interference by politicians, the law and the press itself escalate the execution story into one that can’t be passed up, even if it also means passing up a life of tranquility.

The contrast of Walter and Bruce is apparent within the opening minutes but it’s hard to imagine the attraction (other than physical) of a cad like Walter. Then the film contrasts the prospect of life with Walter and life with Bruce and Hildy’s attraction comes into focus. Walter joins the couple for lunch and, searching for a method of delaying their retreat, talks to Bruce about his job as an insurance salesman. “I figure I’m in one business that really helps people,” Bruce says when Walter asks about life insurance. “Of course, we don’t help you much while you’re alive. But afterward, that’s what counts.” Walter is trying to fill pages with new stories every day. Bruce is strategizing for death.

It’s apparent from the moment she opens her mouth that Hildy is a creature of Walter’s world, not Bruce’s. Her skill as a writer is the subject of rival reporters’ gossip. Her peers read the beginning to the story she writes about the looming execution and marvel at it. When she taunts Walter by tearing it up, we see their panicked faces as she destroys a creation they couldn’t hope to replicate.

It’s that respect for the prose that makes the prospect of Hildy and Walter reteaming exciting – the talented writer and the appreciative editor. The movie features a prison break, standoffs at gunpoint and a dramatic defenestration. Barely a breath is taken between these actions and the rush back to the phones and typewriters. That’s where the real action happens.

An exhilarating scene late in the movie contains a three-way shouting match between Hildy as she tries to bang out the final story, Walter as he tries to rearrange the paper’s layout and shut Bruce up, and Bruce who has had enough of the whole debacle and insists Hildy leave town with him. The dialog accelerates and overlaps nearly to abstraction and without the benefit of rewind we go off the impression of what everybody wants. Listening carefully, we can hear Hildy spell out what she gets from writing for the paper and why she needs it. “Can’t you see this is the biggest thing in my life?” she shouts at Bruce, then, perhaps getting a line turned around a bit, “Just because you won’t listen you say I don’t love you.”

For Hildy, writing on a deadline is an expression of something as deep as romantic love. She’s oblivious to Bruce the person during this rant, continually returning her gaze to her typewriter. Later she’ll have trouble remembering if he was there or what he said. As she bangs out her story she’s only aware of him as another obstacle to hurdle before deadline. Bruce for his part sees the truth even if he doesn’t understand it. “You’re just like him and all the rest!” he says. Her retort: “Well that’s what I am.” (The lines in this scene would be agonizingly on the nose if they weren’t delivered at supersonic speeds. Dissecting the dialog is like slowing down hummingbird footage.)

Bruce exits in a huff and Hildy and Walter continue shouting at each other as she types up the story. Walter’s abuse of Hildy’s writing and her alternately volleying the criticism back and absorbing it to make something better – even as they both know she’s kicking ass – is a wonderful detail. Hildy never fights with Bruce and never creates anything meaningful with him. She and Walter shoot flames at each other and forge a story in the heat. After this process, it’s no wonder Hildy doesn’t feel the need to bear children.

Throughout the film Walter’s tactics for retaining Hildy change as circumstances change. He argues she should stay because she loves him (ineffective), on moral grounds (ineffective – Walter has no standing in moral matters), or because it’s a career opportunity (temporarily effective). In the end he succeeds (possibly accidentally – Walter’s intentions have become so suspect by this point it’s tough to tell if he’s conning Hildy, the audience, himself or some combination of the three) simply by not giving up on her as – Hildy’s own description of herself – a newspaperman. Hildy tearfully reveals her fear that she could really walk away from the newspaper life. She takes her writing job back. She and Walter will remarry and, wouldn’t you know it, their honeymoon route just happens to take them by their next big story.

This fantasy of journalism as a thrilling pursuit akin to swashbuckling has only grown in appeal. Now that scoops need to be reported minutes after an incident happens and the words Fake News have stomach-churning associations, His Girl Friday’s scenes of reporters calling in exaggerated stories and begging the warden to hang a criminal before filing deadline have the anachronistic appeal of high seas piracy. Technology changed the game by removing the deadline aspect, and this exacerbated a diminished emphasis on the craft of writing a story. It’s depressing to consider a Hildy deprived of an editing staff – or readership – that thinks her job could be handed to a cheaper cub reporter. Maybe she’d be one of the hundreds of talented writers holding onto a job by a thread, lucky to see her words posted under a clickbait headline. Or maybe she’d be in Albany with Bruce.

The movie leaves no doubt that Hildy makes the right decision in the end. Walter is conniving, self-serving, and ego-driven. So is the job Hildy adores and where she thrives. Picking Walter is picking the life that gives her professional and creative satisfaction, and if basing a marriage on these things is a crazy way to go about it who has time to worry? That’s yesterday’s news.

—–

Strays:

– Since The Front Page gets adapted pretty frequently, maybe it’s time for a version that doesn’t fuss about the genders and keeps the romantic angle? Anybody up for this as the next Amy Poehler / Tina Fey project?

– Ya’ll, I love this movie so much. Humor on many levels – one-liners, back-and-forth dialog, character-based, situational – and I find something new to laugh at every time (this time it was poor man-on-the-lam Earl’s moan of fatigue when he’s forced to hide in a desk, he’d rather just be shot). It embraces its stage roots in the right places and breaks from them in the right places, adding to it a love story that’s based on respect and mutual interests rather than vague, mooney-eyed nonsense. Russell’s crying near the end always brings a tear to my own eye. There’s no place for those overwrought violins of so many mid-20th century love stories – they’d just be drowned out by arguments and typewriter keys.

– The film fell into the public domain years ago so you can watch it any number of ways in any number of qualities on any platform. You can be watching it right now!