Firefly takes place within an American myth. Specifically, it takes place within the myth of the Confederacy fighting the Union over states rights; a scrappy underdog who fought for freedom and lost, but is ready to rise again. Needless to say, this was mildly embarrassing when the show first aired in 2002, and is unforgivably tasteless in 2017 – this article was written just a few days after statues commemorating Confederate soldiers were toppled down across America almost literally overnight. It’s impossible to ignore that Firefly conveniently strips out things like, you know, slavery for the sake of peddling that myth, and impossible to ignore just how compelling that myth can be stripped of those vile realities.

“We can’t die, Bendis. You know why? Coz we are so… very… pretty.”

We begin the episode and the show meeting Malcolm Reynolds, the scrappiest, underiest, doggiest scrappy underdog on television. He’s practically giddy with joy as he fights for truth, love, and justice; even the fact that men around his are dropping like flies isn’t enough to dampen his heroic speech. It’s only when he learns that his side has surrendered that we see the life drain from his face, and so the basic conflict of Mal is set: the need to believe, heart and soul, in the ability to do good, and the need to survive in a world where that’s impossible. Drama doesn’t need an origin story explaining psychology, but having one can turn a dramatic protagonist from everyman into folk hero.

(We also see that it wasn’t trauma that made Mal into someone who bends and breaks the rules; he’s happily breaking the chain o’ command for practicality before that ever happens)

The next five minutes brings us to Mal’s present. He’s captain of a ship called Serenity, and when we find him he’s currently in the process of stealing salvage from a wrecked ship; things turn tense when an Alliance ship shows up, so they fake a civilian distress signal and get the hell out of there. Like Star Wars before it, we learn so much about how our heroes belong in the world just from set design; Serenity is dank, dark, largely wooden, and full of lots of little nooks and crannies, and the only thing uniform about the crew is that they’re all able-bodied humans. The Alliance ship, on the other hand, is much closer to the Star Trek mold, sterile and well-lit, and even receives more traditional swooping hero shots than the offbeat handheld that Serenity gets (the effects crew would go on to work on the Battlestar Galactica remake, using the same aesthetic for a slightly different effect). Our grubby little heroes just barely get away with their load and cheer their victory; Mal accepts the win more wearily.

The actual meat of the plot spins out of this theft; while they didn’t get ID’d, they were identified enough to make selling the cargo inconvenient, and they’re forced to turn to a woman on a border planet who once shot Mal (hilariously, Mal is the only one unconcerned about that – “That was a legitimate conflict of interest!”). He also chooses to take on passengers, acknowledging this still isn’t enough to get them through another day, but allowing them to pass through Alliance space with less trouble. The crew of the Serenity live on the edge; this is sold through details just as often as plot, as the travelling preacher Shepard Book bargains his way onto her by giving Kaylee fresh fruit, and cooking for the crew. At the same time, it’s clear Mal belongs on the edge, because he loves bullshitting his way through life – mysterious passenger Simon pokes at his story of dropping off medical supplies at Whitefall several times, and each time we see the gears turning in Mal’s head before he gives a funny and/or awesome answer.

“What do you pay him for?”

“What?”

“I was just wondering what his job is – on the ship.”

“Public relations.”

Talking about the passengers is also a good jumping point for talking about something small within the episode but crucial to the success of the show: the diverse moral universe. Whedon has described the show as nine people looking into the black and seeing nine different things; this has the upshot of nine different actions these people will take. Morality is almost a creative force on this show – Kaylee creates joy wherever she goes, Jayne creates ownage, Book creates spiritual fulfillment.

Joss Whedon is one of the most influential writers alive, touching not just diverse genres, but diverse mediums; his presence is felt in television, film, comic books, literature, and even video games. And if there’s any specific technique that acts as his claim to fame, and is in those television shows, films, comics, books, and games, it’s his ability to construct a joke – to set up an idea, and knock it back down. But what he understands better than many of his descendants is that jokes work much better delivered by a character, and that’s where his understanding of morality comes in.

In weak stories, jokes could be delivered by any character; in Firefly, Mal has jokes both for him and at his expense, and Jayne has jokes for him, and Inara has jokes for her, and so on. Jayne’s the best example for this actually – one could see a crap show where all his jokes are either abject stupidity, other characters joking about his stupidity, or inexplicable moments of brilliance. Here, he’s allowed to own jokes like “Ten percent of nothing is, let me do the math here, nothing into nothing, carry the nothin’…” or “Pain is scary!”. The joke isn’t just funny on its own, it’s funny because it’s such a Jayne-specific thing to say, and sometimes it leads to real consequences, like Mal kicking him out of dinner for embarrassing everyone.

And as always, the diverse morality makes it all the more meaningful when people do connect. Inara and Book connect immediately despite one being a prostitute and one being a priest, because they share a sense of social grace that everyone else lacks (or deliberately punctures, in the case of Mal); Mal and Kaylee share a sweet sentimentality, almost an older-brother-little-sister relationship (I imagine they have very similar working-class backgrounds). And, of course, the second half of the episode is the burgeoning respect developing between Simon and Mal.

“I don’t believe there’s a power in the ‘verse can stop Kaylee from bein’ cheerful. Sometimes you just wanna duct-tape her mouth and dump her in the hold for a month.”

[kisses Mal’s cheek] “I love my captain.”

When they’re out in space, a transmission is sent to the Alliance, and Mal automatically assumes it’s the creepy guy who’s been asking too many questions; but it turns out to be Dobbs, the nerdy guy nobody was paying attention to, and he is in fact after Simon. In the chaos, Kaylee gets shot and Dobbs gets tied up, and Simon, the only doctor onboard, thinks fast and refuses to treat her unless they flee Alliance space. This decision is a fulcrum of the episode; Whedon wrings as much tension out of it as he can and throws in as many perspectives as possible, from Zoe’s pragmatism to Book’s steady preacher voice to Jayne’s ownage. In the end, Mal reluctantly leans towards saving Kaylee.

After it’s established that Simon’s done everything he can for Kaylee, Mal decides to go through Simon’s stuff to see what’s so damn interesting, and finds a naked, screaming girl; this is Simon’s sister, River. Suddenly, Simon’s decision-making process is horribly clarified – not just in what he’s done to save her, but in how he explains their past, as he talks just slightly too long about how awesome his sister is. He sacrificed everything to save her from the Alliance, and he’ll willingly sacrifice so much more. Mal makes a big show of not giving a shit, and tells Simon he’s dropping them off at the next stop, and even Inara’s threat to leave the ship with them isn’t enough to sway him (frankly, he sees that as a bonus, protecting her as well). Mal fully believed that Simon was just some asshole rich kid before hearing his story; in return, Simon dismisses Mal as some filthy pirate, which Mal can let go a lot better than Simon’s insinuation that Mal has any loyalty to the Alliance.

“I believe that woman’s plannin’ on shootin’ me again.”

After a little sidebar where we’re introduced to Reavers, the spooky boogeymen of space, Mal, Zoe, and Jayne land on Whitefall to meet Patience. We discover the cargo Mal and friends are selling is actually a scifi food, capable of feeding a whole family for a month (“Longer, if they don’t like their kids too well.”). This is mostly unnecessary aside from adding to the whole Robin Hood aspect and showing how shit life is on border planets, but it’s funny and cute and scifi enough to work. Unfortunately, Patience has to complicate things by trying to get the food without paying for it; Mal kicks off a firefight, traps her under a horse, and lets her know exactly who he is: he does the job, and then he gets paid.

Meanwhile, Dobbs breaks out of his holding cell and causes chaos for the crew; Reavers show up all of a sudden, putting an extra clock on the table. When Simon gets the drop on him, Dobbs buys himself a few extra minutes of time by appealing to his sense of law; when Mal rocks up, he shoots Dobbs in the face without even breaking stride – both total fucking ownage, and a rejection of the rule of law.

The rest of the episode is denouement. Wash and Kaylee save the day by fleeing the Reavers, Wash and Zoe happily go off to fuck, Book confers his moral conundrum over the violence with Inara (who advises that maybe he’s exactly where he needs to be; he needs this ship as much as the ship needs him), Simon confirms his love for River, Mal gets Jayne to admit that Dobbs offered him money (and the money wasn’t good enough), and most importantly Mal and Simon reach an understanding.

Specifically, Mal offers Simon a job as medic. Practically speaking, it makes sense; they pretty clearly need someone with Simon’s skills onboard, and as Mal points out, it’s a lot safer for Simon and River to jump from place to place than it is to settle in one spot. But I believe Mal recognises a fellow loyal man in Simon; Mal saw what Simon was willing to do for his sister, and despite all pretensions he understood completely. Aside from the practicality of someone capable of deep loyalty, he needs to know this unbreakable love can exist, and Simon can be a constant reminder of that.

That’s what makes Firefly so much more than left-libertarian-flavoured Confederate wish fulfillment. Mal’s values may be that all-American gung-ho rock-flag-and-eagle FREEDOM junk, but his journey is how those values are impossible to live up to, and yet impossible to give up on, and how it’s not the Alliance that makes him an underdog, but his compulsion to walk that strange and difficult path.

“Well, we’re still flying.”

“That’s not much.”

“It’s enough.”

SCATTERED THOUGHTS

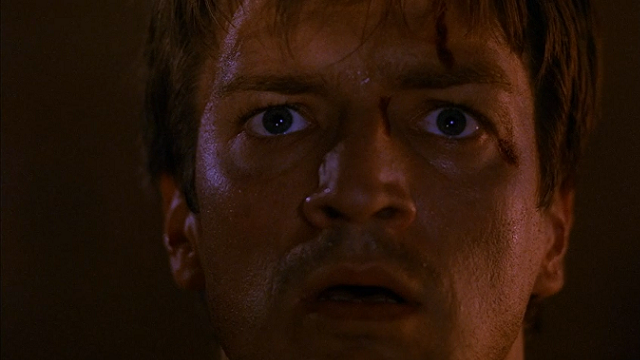

- I can’t look into that featured image too long without crying in sympathy.

- The theme song has become somewhat controversial over the years amongst Firefly fans. Mark me down as someone who unabashedly loves it – it’s earnest, but it’s an earnestness I identify with, and I find myself singing along every time I go through the series.

- The opening heist is the first and last time the Alliance is presented with any sense of moral greyness, with the Alliance commander dude sincerely more concerned with helping innocents than chasing down thieves. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing – for one, we’re mostly looking at this series from Mal’s POV, and he’s pretty set against the Alliance – but if you’re sympathetic at all to the idea of an authoritarian government, it can be frustrating to see a constant parade of Evil Assholes. Whedon is much more forgiving of Mal’s views than, say, Matthew Weiner is of Don’s on Mad Men.

- On the commentary for the pilot, Alan Tudyk observes that there’s a climactic shot where he’s clearly only pretending to hold onto a steering wheel. Once it’s pointed out, it’s impossible to ignore.

- The pilot has a few very jarring stylistic choices – there’s a few jump cuts in Inara’s scene with her client, and there’s one shot I’ve always hated, where Whedon pulls the camera out on Badger as he replies to Mal’s line “Wheel never stops turnin’, Badger,” with “That only matters to the people on the Rim,” making a thematic statement go from on-the-nose to hit-in-the-face-like-a-brick. These choices would vanish in the second episode and be more artfully executed in time.

- The staging of Mal shooting Dobbs is ridiculously cool. He’s walking up behind Simon, not even in full focus yet, when he draws and fires his gun within one shot, making it look even more offhand.

- Welcome to the regular Firefly essays! These will go up every Monday, 5pm Seattle Time (or Tuesday, 9am Australian EST).