Antoine de Saint Exupéry had exiled himself in America when he wrote his existential modernist children’s book, The Little Prince. Though appropriate for all ages, The Little Prince contains a nested story that analyzes the absurdity of the modern landscape and the growing disconnect of modern capitalist society. The narrator is an aviator who crashed in the Sahara desert, only to find The Little Prince, a boy who said he came from another planet inhabited only by volcanoes and parasitic Baobab trees. After he fell in and out of love with a rose, The Little Prince, looking for happiness, traveled to various planets defined by different aspects of modern society and ended up in the desert. With all of this complexity, The Little Prince is a story that changes for the reader as they grow up. As a child, the reader relates to The Little Prince, and as they get older various aspects start changing in their meaning until one figures out they’re actually the narrator trying to overprotect people from life.

The first half of Mark Osborne’s The Little Prince is a Cliffs Notes of the original book. Osborne adds a layer of metaness to the original story. The main character of this edition is The Little Girl, a young child who is being pushed to work and study her childhood away. She and her mother move to a new house to get into a good school, and wind up living next door to a kooky old aviator, The Narrator. The Little Girl befriends The Narrator, and spends her summer learning the Cliffs Notes of The Little Prince.

The second half takes the abstract concepts of The Little Prince and hammers them home into a modern dystopian girl power storyline that explains EVERY SINGLE IDEA in excruciatingly plain detail. The Little Girl flies away to a horrific capitalist planet in search of The Little Prince who has grown up and forgotten his identity. The planet gathers every one of the planet people and makes them into a corporate enemy that wants to possess all of the stars and turn everything special into a commodity. And, of course The Little Girl has to gain her girl power and save the planet.

Ironically, in strapping the rather abstract original book to such a linear, boring, and common dystopian plot, Mark Osborne winds up grinding the special novel into a commercial friendly commodity. This overtly explanatory section doesn’t trust the readers to put the pieces together and apply the lessons to their own lives. Instead of taking his time with the novel and letting it breathe, Osborne cuts the story to its bones so his tacked on story could have prominence, thus completely destroying all that made the novel special.

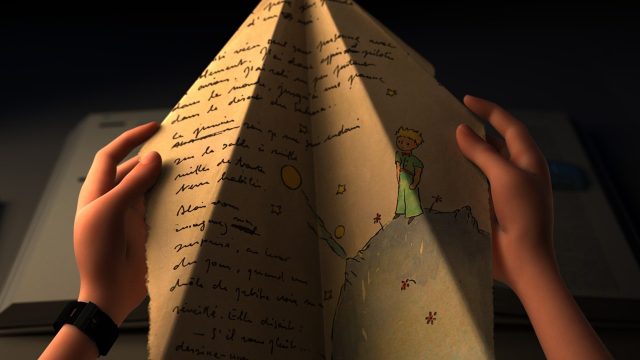

Far from being a complete trainwreck, The Little Prince is actually a genius movies in flashes. By adding in The Little Girl, Osborne actually keeps the storytelling conceit of the original book. The Narrator can actually be a narrator and the reader has become its own character. To keep the various story lines straight, Osborne has developed two separate styles. All of the new story line is depicted in a basic modern CGI style rendered with less imagination than a Fox Animation film. The original book is given an artificial papier mache style halfway between Little Big Planet and Paper Mario. The dichotomy accentuates both the fantasy and the colorful lessons of the story, even as they grow into parallel tragedy.

When The Little Prince works, it’s gangbusters. When it doesn’t, the movie is insufferable. It makes a frustrating experience that soars to the highest successes, and crashes into the mountain of stony failure. Rare is the movie that works in and fails for exactly the same reasons in different scenes. Mark Osborne’s The Little Prince is that rare experience.

The Little Prince streams on Netflix