Herbert Ross’s The Last of Sheila is a sharp, tart, and fizzy cocktail. The characters are almost all fabulously unsympathetic, but they’re riveting anyway: it doesn’t matter if they are, nearly to a one, vicious, shallow, and self-obsessed, because they’re also witty, well-acted, and human. This was an obvious (and admitted) influence on Rian Johnson’s Glass Onion, but here there are no bastions of moral clarity to register disgust and rise above the muck. There are only the suspects, and wallowing in muck has rarely been so entertaining.

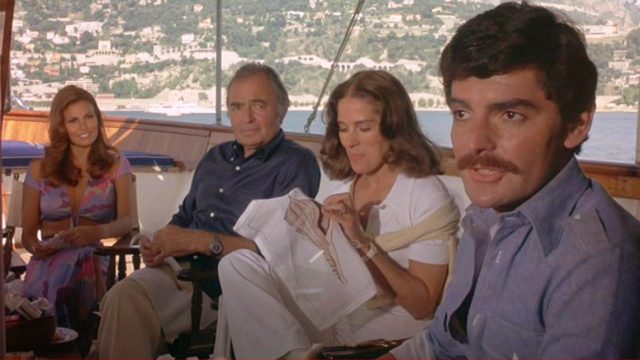

High-powered producer Clinton (James Coburn) is organizing a party for his nearest and dearest–except since Clinton is openly and gleefully loathsome, a “minor-league sadist,” it’s also a party for everyone he loves to prod. To him, they’re all grasping failures, and if they want to wet their beaks on his next production–a big-budget picture about his wife, Sheila, who died last year in a hit-and-run–they’re going to have to play a game, a kind of elaborate scavenger hunt of their own secrets and peccadilloes. The players are struggling screenwriter Tom (Richard Benjamin), currently stuck in the professional hell of doing rewrites on other people’s scripts; Tom’s wife, Lee (Joan Hackett), who grew up in Hollywood but never grew into it; midlist agent Christine (Dyan Cannon), who’d love to place one of her clients; Philip (James Mason), an established director whose career has dwindled to dog-food commercials; glamorous but fragile actress Alice (Raquel Welch); and Alice’s rough-around-the-edges husband, Anthony (Ian McShane), who doesn’t quite fit in. They could all use a break, and Clinton’s game is a guarantee that not all of them will get it: it’s a game that’s meant to have at least one loser.

Then there are the secrets, handed out on type-written cards. Shoplifter, says one. Homosexual, says another. Little child molester, says a third.*

What’s the complete line-up of secrets? Which secret belongs to whom? What’s Clinton driving at, anyway?

Those questions are still open-ended when Clinton is found dead–and it’s here that The Last of Sheila really gets going. Technically, if you’re paying close attention, it’s not that hard to promptly solve Clinton’s murder–though I have to admit that I didn’t, not the first time through. In any case, it’s not the point. As in many of the Golden Age mysteries the film’s writers–the superb duo of Stephen Sondheim and Anthony Perkins–clearly admire (they’re even strewn around the yacht to drive the point home), the murder is mostly just our entry point into a lively world of corruption, elegant insults, vivid character sketches, and mild pathos. (Some of the best acting comes when the characters, as part of Tom’s detective scheme, have to claim their secrets from the pile: Dyan Cannon takes maybe twenty seconds and imbues her character with a light poignancy that winds up being unforgettable.) Best of all, solving Clinton’s murder doesn’t end the story. Instead, in a move that cements The Last of Sheila‘s greatness, we–while staying in the muck–switch “detectives.” Someone else has a few lingering questions, and we glide gloriously towards one of my favorite dark, funny, and mean endings in cinema.

I appreciate Ross’s direction, especially towards the end, and I have nothing but praise for the actors, especially Coburn, Mason, and Cannon. But this is a writer’s movie, and so I have to give the lion’s share of the credit to Sondheim and Perkins. The structure of this film is perfect, and there are so many clever touches here. I usually don’t worry too much about spoilers, but here I’m saving some bits of praise to go behind spoiler-cuts in comments: my favorite parts of this movie deserve to be experienced for the first time with fresh eyes. Just know that it amply rewards rewatching. I’m sure this won’t be for everyone–again, most of the characters are extremely far from being traditionally sympathetic–but if you want a bracing dose of something smart, cruel, and acerbic, The Last of Sheila is now streaming on the Criterion Channel.

* Content note, of sorts: You could do a whole multi-episode podcast on what the hell is going on with that “little child molester” secret, how the characters react to it, and how the film seems to expect the audience will react to it. It’s handled very oddly, even within the context of a 1973 milieu. The characters (and even, to some extent, the film itself) are far more cavalier, unquestioning, and ambivalent about it than you’d expect. It’s interesting to discuss, but it’s also another reason some people may understandably want to avoid this.