A mystery is an excellent and oft-used device to keep the end of your story well away from the beginning. Cozies are famously more about baking, knitting, bookselling, and small town living than they are about who’s committed this installment’s peculiarly bloodless crime, but hardboiled fiction has its own legendary examples: if you have no idea who killed the chauffeur in The Big Sleep, that’s fine, because Raymond Chandler didn’t know either. He didn’t care. In some cases, death is just a trellis to hold up what the story is actually cultivating. Sometimes that’s atmosphere, sometimes it’s insider detail, sometimes it’s setting, sometimes it’s philosophy ….

Like almost everything else in fiction, this can be done well or badly. Samuel Fuller’s 1959 film The Crimson Kimono does it well even if it doesn’t do it smoothly. You’ll notice that huge swathes of the film seem to entirely forget about the murder of burlesque performer Sugar Torch (Gloria Pall), but you probably won’t mind too much. Fuller gives you too much else to think about.

Assigned to the case are easygoing Detective Joe Kojaku (James Shigeta) and his partner, the more bullish Detective Sergeant Charlie Bancroft (Glen Corbett). Joe and Charlie served together in Korea, and they’ve been inseparable ever since. Even when they clock out, they go home to a shared apartment, a home they’ve poured all their money into; they’re each other’s biggest and most significant lifetime commitment. They have an easy, comfortable rapport, each sliding into the other’s company like a pair of worn-in shoes. This is all true, anyway, until they meet just-starting-out artist Chris (Victoria Shaw). Chris is a witness–she did a painting of the victim, on commission from a man who could be the killer–and she soon becomes more. Charlie falls first. Chris is the one, he says, and while he wasted a lot of years before he met her, none of that matters anymore. They strike up a flirtation, but Chris’s feelings for him are tentative and shallow. What she soon feels for Joe, on the other hand, is the real thing–and Joe feels the same way.

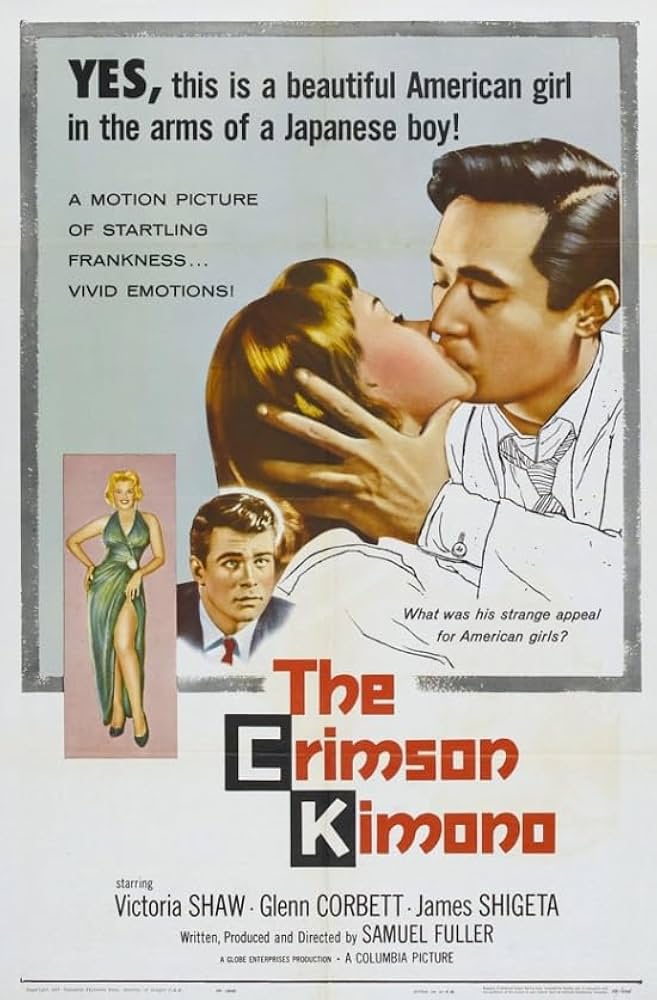

It’s a messy love triangle, and Fuller makes sure it can’t resolve too neatly. And if the bitter interplay of love, loyalty, resentment, and betrayal weren’t already complicated enough, the entanglement makes the Japanese-American Joe freshly, achingly aware of the possibility that both his white partner and white girlfriend might have not-so-buried prejudices about him. The film’s answer here may seem too safe–in essence, while Joe briefly believes that Charlie’s newfound fury at him is racially tinged, he comes to understand that it’s not, and that maybe jumping to that conclusion was only a way to salve his own conscience at being, as We Hate Movies would say, Mr. Stealyagirl–but I think it’s more complex than it seems. Fuller is acutely aware that anti-Japanese sentiment was alive and well: one of the most oddly tender scenes features Charlie trying to feel out whether or not an already-over-him Chris has slighted Joe on just those grounds. And Chris, in fact, initially decides that the only reason Joe is resisting her is because of some uniquely Japanese hang-up and not, say, the fact that his best friend is already in love with her. We don’t have the sense that Joe and Chris are kicking off their romance in a world that is entirely prepared for them, and that Joe is foolish to think anyone could care. The original poster alone would correct you on that front:

The world cares (and stares) very much. Chris may even care a little, though not in a way that can’t be overcome. Joe is only wrong when it comes to Charlie, and that lends the movie’s happy ending a memorable and bittersweet edge. Sometimes you get the girl, even in a time when that might seem impossible, but you lose something else in the process.

The romantic drama is the heart of The Crimson Kimono, and by casting James Shigeta as a charming, charismatic, flawed, and overall well-rounded romantic lead, it has, like much of Samuel Fuller, aged well. But it isn’t even the main reason you want to watch this.

Where The Crimson Kimono really excels is in its matter-of-fact and almost journalistic portrayal of late-’50s Little Tokyo. This is a loving portrait of a very lived-in environment. Almost any other movie of the time would orientalize the hell out this setting, treating it as intrinsically mysterious and Other; Fuller just sees it as the world. A dojo regular worries about his family finding out he agreed to appear in a burlesque show. An old man reserves a Buddhist temple to hold a lonely, touching memorial for his son. A rice cake factory is an ordinary place to work. A kendo demonstration serves as a catalyst for Joe’s simmering anger, and it isn’t framed as any more “exotic” than it would be if he fouled Charlie too many times on a basketball court. This is a vividly observed world full of connections, ordinary street life, and social history. Not only have I never seen an English-language film from this era be so nonchalantly appreciative of and at home with Japanese-American culture, before The Crimson Kimono, I wouldn’t even have imagined such a film existed. (If there are in fact more movies like this that I’ve just never come across, please let me know.)

The trellis may get lost beneath the ivy, but when the ivy is a romantic melodrama this heartfelt and a bit of tourism this rare and wonderful, I for one don’t care. I have nothing but kudos to Fuller for what he created here.

The Crimson Kimono is streaming on Amazon Prime and the Criterion Channel.