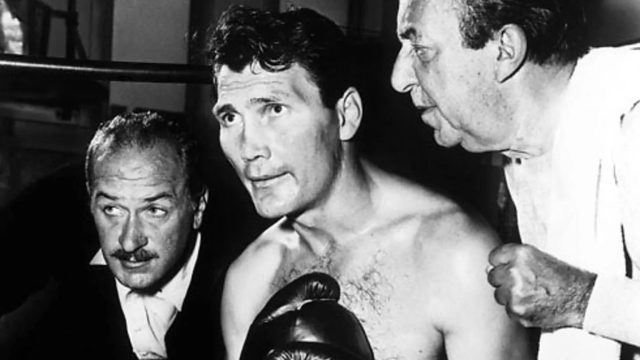

The original Playhouse 90 broadcast of Requiem for a Heavyweight gives us the swan song of “Mountain” McClintock (Jack Palance), a battered, used-up boxer who is forced to leave the ring for good. We meet him right as his career comes to a close; we know that he lost his last fight, and that it’s left him a swollen, bleeding, semi-conscious wreck one bad hit away from total blindness, but we also know he lasted more rounds than anyone would think. He has become an official loser, but he still has his pride. As he says, he was in 111 fights, but he never took a dive.

Mountain has a whole life behind him, one that’s left him punch drunk and beaten out-of-shape, with permanent cauliflower ears. But he’s still a young man. There is no cozy retirement for him at this age, only the chance to wobble into a drunken twilight where he joins the other old fighters at the bar, reminiscing as he drinks himself to death. His only chance in life is to reinvent himself–but he has no training, no experience. He’s loyal and sweet, but he’s easily overwhelmed, more used to being led than striking out on his own.

And his manager, Keenan Wynn’s amoral but not uncaring Maish, is heavily in hock, and Mountain is his only way out of it. Soft-hearted cut man Army (Ed Wynn) frets over a system that encourages men like the two of them to hitch their stars to one man’s increasingly broken body, but he doesn’t have a whole lot of solutions either. The bet he can do is nudge Mountain towards Grace Carney (Kim Hunter), an employment office worker who is moved by Mountain’s plight. Meanwhile, Maish, with increasing desperation, pushes Mountain towards wrestling, where the wins and losses are scripted and Mountain’s Tennessee background can be boiled down to kitschy costuming.

Requiem for a Heavyweight is good at emotion, both in broad swathe and in nuances. Palance is a raw revelation here, playing Mountain as someone who can’t understand everything, at least not all at once, but who feels it all, who knows he’s clinging to his pride and dignity with bruised fingertips. It’s a spectacular performance, and a nakedly vulnerable one. It would be a little too much to bear if we didn’t have the Wynns as back-up, especially son Keenan. Another play would make Maish–who manipulates and uses a young man who clearly adores him–into a clear-cut villain; Requiem sees him clearly enough to know that while he may be a parasite and a puppet-master, he loves Mountain back … though they both might be better off if he didn’t. If he had cut ties with Mountain back when Mountain first started losing, he’d be fine–but he didn’t. Even now, he doesn’t want to. They’re one scene away from being a Mountain Goats song.

If the film has a flaw, it would be that the story’s natural shape tends to tragedy, and you can see Rod Serling* putting all his effort and talent into making it one of Tolkien’s eucatastrophes instead. But you can also see that tug away from rock bottom as the reason the story exists at all: to give a future to someone who could so easily not have one. I can’t be too mad about it, not when I felt a genuine, shaky sense of relief at the tentative–and qualified–sense of hope we’re left with here, and certainly not when the absence of that outcome might have meant the absence of Requiem altogether.

Requiem of a Heavyweight is streaming on Tubi.

* One of my all-time celebrity crushes, for the record.