An unusual, nuanced, and quietly gripping drama of conscience, Longford is also a reminder that even my worst enemy–director Tom Hooper–can occasionally produce good work.

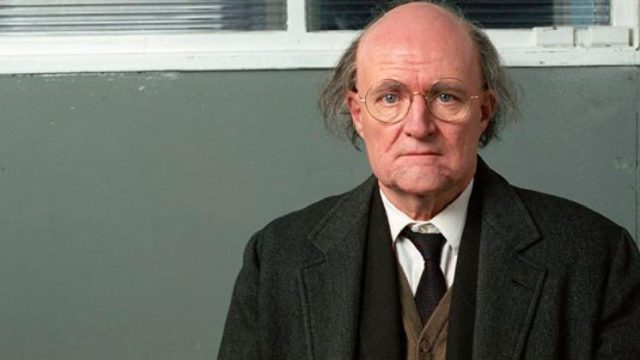

The film centers on the real life story of Lord Longford (Jim Broadbent), a devout Catholic strongly committed to the charitable work of visiting prisoners. Broadbent is the perfect choice for the role, imbuing the aging Longford with both holy foolishness and human vanity. His principles are genuine–and he lives them out with a touching commitment–but so are his blind spots, and both are capable of getting him in trouble. Peter Morgan’s screenplay follows Longford closely and without judgment through what will turn out to be the greatest spiritual test of his life, bringing him to a crisis not of belief but of action. Is he willing to risk his reputation? Willing to risk being wrong? Risk feeling foolish or hurt? Risk doing harm?

The narrative, such as it is, is simple. Longford receives a request to visit Myra Hindley (Samantha Morton), one of the deservedly infamous Moors Murderers. Against his wife’s advice, he pays her a call–and finds her sympathetic and vulnerable, overwhelmed by her circumstances. He wants to believe that her part in the child killings was, at heart, involuntary, brought about only because she was in a kind of obsessive thrall to Ian Brady (Andy Serkis). He nurtures this belief by sheltering himself from the details of the actual case. He becomes Myra’s champion in the press, advocating for her to at least be considered for parole.

It causes conflict with his family and a barrage of hate mail–but it is, we see, possibly still better for Longford than the alternative, which is now a professional life of dwindling respect and limited usefulness. Myra’s cause is a moral conflict with real significance, and it’s personal, intimate, and immediate. (At one point, he tries to shelter his family from the harassment they’re getting by campaigning against pornography instead, and we see how that makes him appear: dotty, past it, ineffectual, a laughingstock. He gets dubbed “Lord Porn,” and the nickname follows him for years.) All of this means that Longford’s belief in Myra and his promotion of her cause is both a genuine act of conscience and inextricably tied up in his own self-image: the man he is, the man he wants to be, and the man he wants to be seen as.

Something has to give, and it eventually does–first dramatically and then, after some years, spiritually, giving us two separate, shattering moments that play in very different keys.

It’s a beautifully done film, tight in its focus but immense in its concerns. It’s a little talky, but it’s at least able to ground that talkiness in believable circumstances: this is the kind of scenario that often leads to numerous interviews and awkward, fraught dinner conversations. The film handles a number of tricky aspects gracefully and relatively organically–for example, the sociological big picture for Hindley’s lack of parole comes up only when another character gets interested in the case, as that isn’t Longford’s angle on it at all. It’s definitely a movie about Christian philosophy, but it’s of interest, I think, to anyone more broadly interested in stories about characters struggling to live out specific principles or about conflicts between the purity of an ideal and the messy and even dangerous results of trying to implement it in a very impure world.