Devil in a Blue Dress is now on Tubi, allowing me to finish off my triptych of Carl Franklin recommendations.

All three of Franklin’s top films demonstrate his deft and versatile use of noir, evocative settings, and clever plotting; One False Move may be the best and most surprising of them, but Devil in a Blue Dress is undeniably the most significant. Like the Walter Mosley novel series it’s based on, it fills a dramatically under-served niche; by exploring Los Angeles’s post-war tensions and opportunities from a Black perspective, it manages to both nail classic noir style and concerns and bring something new to the table.

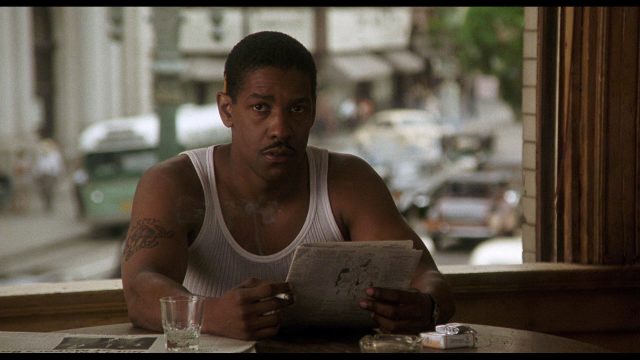

Denzel Washington stars as Easy Rawlins, a newly unemployed war vet–sociable but full of coiled intensity, a man keeping a tight grip on the ordinary-but-tenuous happiness he knows he’s earned.

Joppy, a bartender friend of Easy’s, introduces him to a white man, DeWitt Albright, who might have some work for him. The job is simple: unearth the elusive Daphne Monet, the fiancée of wealthy local stalwart Todd Carter, who just dropped out of the mayoral race. Daphne’s known for crossing the color line, so Albright suspects she’s vanished into a demimonde of Black-owned nightclubs; if he starts asking questions there, he won’t get any answers, but Easy will.

Already behind on his mortgage, Easy can’t afford to decline. And hey, it’s just pointing a lovesick man towards his wayward girlfriend, right? If it’s not … well, when he starts out, he can still make himself believe that that’s what it is, and he can believe that if it’s not, it’s not any of his business. One of the questions of Devil in a Blue Dress is who and what you owe your allegiance to, and to the extent that it poses any answers, they aren’t simple ones that relieve all your worries.

Nothing is too easy, and almost nobody is all that innocent. Easy moves through an LA where everybody has an angle and an agenda. Ask a question, and you pay $10 for the answer–at least. Blackmail, murder, illicit sex, scandal, prejudice, horror, and injustice all run rampant, and the police aren’t a solution but only a brutal additional complication.

While Devil in a Blue Dress could easily coast on its atmosphere, historical niche, and performances, it really grounds itself in a quartet of memorable performances. The first is from Washington, whose sense of presence has rarely been used better than it is here; he makes Easy instantly believable and iconic, someone both archetypal and grounded in his own time and place.

Then there’s Don Cheadle’s Mouse: Easy’s old friend, electric and loyal and utterly comfortable with his own propensity for violence. He’s Easy without the conscience or inhibitions or desire for the trappings of a settled, ordinary life, and like Easy, he falls nicely into a detective genre archetype–the sidekick who ensures the protagonist’s hands stay clean. Cheadle arguably steals the picture, proving yet again how supporting roles are often more vivid than their lead counterparts.

Mouse’s opposite number is Tom Sizemore’s Albright, the professional go-between. He’s a sketchy, mercenary figure, and Sizemore plays him like his superficial friendliness is just a steadily slipping mask over a vast amorality and dangerous unpredictability. He feels more psychologically realistic–and more dangerous–than most noir henchman.

The final piece of the puzzle is Jennifer Beals as Daphne, the woman in question, and Beals gives her a breathtaking sensuality, secrets, and heart. She’s a little hamstrung by having to be both damsel and femme fatale, both archetype and revisionist take, and you can feel that the film is a little less comfortable with her than it is with, say, Easy and Mouse. Beals embodies the part–and its mystery–so thoroughly that it’s easy to overlook that, however.

Devil in a Blue Dress is a sophisticated, well-acted, and handsomely shot film; it’s traditionally satisfying, and you can watch it as straight genre fare and have a great time. The lingering mark of it, though, comes less from its high level of technical craft and more from its ambivalence and messiness, something all the main actors channel perfectly. In a way, Devil in a Blue Dress is more cynical–yet more relaxed about its cynicism, and more confident about how to move forward–than most of its predecessors. Jake Gittes had to be told to forget it, it was Chinatown. Easy already knows the limits of his world and its justice; he’s had to. It’s still worth using what power he has.

Devil in a Blue Dress is streaming on Tubi.