“One great rock show can change the world” — Dewey Finn, School of Rock

“The war was lost” — Leonard Cohen

America is a shithole. The poor and homeless huddle in the margins of streets walked by stone-faced men with guns. The media are uninterested in anything that won’t push the ratings up. The president is a sickened despot, surrounded by lackeys and obeyed with contempt that doesn’t outweigh the fear. The war has been going on so long that its existence is a sore, suppurating and still ignored. Also, there’s a Bob Dylan movie I want to tell you about.

You see, once upon a time Bob Dylan was on a plane with some guy who kept talking at him, wouldn’t leave him alone. And Larry Charles, who was flying with the guy, stepped in out of embarrassment and wound up talking with Dylan for a while, and eventually agreed to make a movie with Dylan in between directing a good chunk of Seinfeld episodes and Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan. As origin stories go, there are weirder.

Or maybe it happened another way. When Dylan was trying to make a weird farcical series with HBO and the story he turned out became something else, turned into Masked & Anonymous. It’s always unclear with Dylan, who left his real name behind more than half a century ago and who’s refused to be pinned down since. The script is credited to Sergei Petrov and Rene Fontaine, two people who definitely exist and have written more things besides this one screenplay. Two more names, two more dodges from a guy who’s spent decades trying to figure out how to plant your feet in a song and not be rooted to the spot by the pundits, the historians, the documentarians, the linguists, the people demanding a Voice and a Conscience and a Light, a person to suffer sins and turn them to tunes, transubstantiation as absolution you can hum along to. Because man, there is so much out there that needs to be absolved and it would be so great if there was one guy who could do it and give me some hope to hold on to.

One way to dodge being the voice and the conscience of a nation is to make a movie instead of a song. A movie about a guy, Jack Fate, who’s sprung from a border prison in that hell country from a few paragraphs ago, sprung to play a benefit show for the victims of that country’s civil war, a show that Springsteen and Joel and all the other stars (oh yes, names are named) won’t touch. A show orchestrated and orbited by a bunch of Dylanesque characters orbiting around Dylan himself playing Fate. There’s John Goodman’s Uncle Sweetheart, the blustering con man/promoter organizing the show; there’s Jessica Lange’s Nina Veronica, the network exec with Faye Dunaway coursing through her veins who’s broadcasting it; there’s Bruce Dern’s cynical Editor sending Jeff Bridges’ hateful Boomer rock journo Tom Friend off to cover the show with Penelope Cruz as girlfriend Pagan Lace in tow; there’s Val Kilmer as a guy who may or may not kill rabbits and may or may not be Fate’s long-lost brother. “Human beings alone with their secrets, masked and anonymous,” Kilmer tells Fate. “We live in fear because we know we’re going to die. It holds us back, knowledge of death.”

But wait, there’s more! Luke Wilson plays Bobby Cupid, a true believer of Fate’s who tries to emulate him in every way. He’s the kind of apostle who’s more rigid than the leader and I cannot fucking stand the guy. The best part of the movie is Goodman bellowing at him to “SHUT THE FUCK UP!” Cupid comes to meet Dylan bearing Blind Lemon Jefferson’s guitar like a holy relic, and at least he’s not wrong there. Giovanni Ribisi is another side of belief, a hollow man looking for a cause to fill him, who moves from the rebels to the oppressors and back depending on how he feels in the moment. “I changed sides, no one even noticed,” he tells Fate on a bus ride a few minutes before he takes yet another stand and is shot to death. Mickey Rourke, Christian Slater, Chris Penn, Angela Bassett, Fred Ward, Cheech Marin, they’re all here. Tracey Walters shows up as a sleazy motel clerk! Is this in the Repo Man cinematic universe? Lange, to an underling, indicates yes: “They’ve got dead aliens stacked up in warehouses.”

There are so many of these people stumbling around as the world goes down the drain and all they can do is talk about it. Like almost all dystopias, Masked and Anonymous vastly overstates the language of the shit times. People speak in aphorisms, riddles, one-liners. Some of these are lyrics from Dylan’s songs (“It’s not dark yet, but it’s getting there”), some are one-liners finding their moment and then darting off. “Keeping people from being free is big business,” Marin tells Dylan, before apprising him of what’s going down on the street. “Two amigos just killed a pregnant rabbit!” “Rabbit must’ve done something,” Dylan replies. Goodman gets a ton of choice lines, like “Does Jesus have to walk on water twice to make a point?” At one point he tells off Bridges:

“Oh, look who’s here. The sultan of sleaze. The thing that came from outer space. Where’d you come from, the World’s Fair? … Look, I was selling porn magazines out of the trunk of my car before you were born. Don’t tell me I’ve had my day.”

But Bridges is the one who uses words to lash, to cut, to dig. He corners Dylan several times for his “story,” ostensibly asking questions but really ranting about sex and revolution and Jimi Hendrix (and where was Jack Fate when Woodstock went down, anyhow?) and the failure of the 60s in general and of one Jack Fate in particular. If Cupid is the convert, Bridges is the apostate, ashamed that he once believed and furious that he still knows a language that no longer gives him comfort. “Tell me,” he sneers at Dylan. “You’re supposed to have all the answers.”

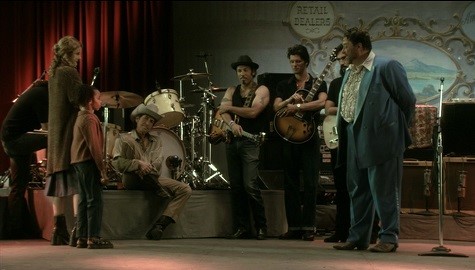

“All of his songs are recognizable, even if they’re not recognizable,” Goodman says at one point as Fate is getting ready to rehearse. For the big TV concert, Goodman’s hired the “best and only Jack Fate cover band in the world” as backing musicians, this is of course the actual touring band of Bob Dylan circa 2003, and isn’t it a little strange how Bob Dylan the writer of the movie makes them disposable here? People he picks up for his performance and can leave behind later. But Charles is more generous, making sure to cover the full band as he films their performances and in two crucial spots, fits all five people playing in the frame. Dylan is the lead but is part of a unit, one that came to play. And it plays a lot.

I’ve watched Masked & Anonymous twice. I’ve listened to its soundtrack more times than I can count. It is my favorite Dylan “album” in a walk. It captures about half of the music in the movie, which is of course all Bob Dylan songs. But it doesn’t have the classics, not really – the biggest hits, “My Back Pages” and “Like A Rolling Stone,” are performed in Japanese and Italian (as hip-hop), respectively. Instead, the album is heavy on 70s and 80s Dylan with a vibe of stubborn weariness, like the apocalypse happened but it hasn’t gotten here yet. It is one of the great hangover albums. There are two live jams from The Grateful Dead and Jerry Garcia, “It’s All Over Now Baby Blue” and “Señor (Tales of Yankee Power).” “Gotta Serve Somebody” gets the gospel treatment it always wanted. Los Lobos livens up “On A Night Like This” (it would take more than the apocalypse to put Los Lobos down) but the Turkish singer Sertab makes “One More Cup Of Coffee” sound like the last one ever.

And then there are the tracks from Dylan and his band recorded live for the movie. Only half of these, which the film recreates as the band rehearses for various audiences, make the official soundtrack, and of course the only song shown in its entirety during the movie – the heartbreaking “I’ll Remember You” – is nowhere to be found. But we do get the joyous rocking out of “Down In The Flood,” the wheezy and fun folk of “Diamond Joe,” the completely straight reading of “Dixie.” Charles clearly shows a bunch of Black people in the audience there, responding to and respecting the song. In case that wasn’t problematic enough for you, a few scenes later Dylan meets the ghost of a man his father killed, a minstrel played by Ed Harris in blackface. “It’s not what goes in the mouth, it’s what comes out that counts,” Harris says. “The whole world’s a stage.”

There is a good chunk of this movie that is not on the stage or about getting ready for the stage, and it ranges from clever to eye-rolling, like any other long-ass Dylan song. At its best, the movie slides through shantytowns and blasted streets full of the desperate and the damned. It is shot like a Vice travelogue of a banana republic but the credits are clear: Filmed Entirely In Los Angeles. That is cutting, the story itself is turgid. It’s about how Jack Fate turns out to be the son of the President, who’s seen in portraits hanging in every room as a generalissimo in his aviator shades and burnished medals. It’s about the flashback to Fate apparently banging his dad’s mistress and getting caught, which is why he was thrown in prison in the first place. It’s about Fate taking an Angry Drive (© Sylvester Stallone, Rocky IV) to the manse where El Presi-Dad lays dying and solemnly staring at him.

This stuff only works as metaphor because as straight story it’s pretty damn dopey, and as metaphor it’s as tedious as “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35.” Much better are the fillips and asides, like when Dylan walks through the weird sideshow of opening acts Goodman has hustled together: carny freaks, a magician, an Abe Lincoln impersonator and what appears to be the actual Pope. There is also a huge sign advertising a Man Eating Chicken, but when Dylan pokes his head in the tent it’s just a guy with a bucket of KFC. I like Dylan when he’s wry and cynical.

But I like him even more when he’s apocalyptic. And everything is coming to a head as he takes the stage for the show. The rebels on the other side of the civil war are advancing, the TV execs (the bosses of Lange, who are all Black – there is some weird racial stuff in this movie) are demanding high ratings, the President is being read last rites. So Dylan takes the stage and he and his band, in one of those tight frames, launch into “Cold Irons Bound.” It’s a song about love as a prison with no escape, no allies: “There’s too many people, too many to recall / I thought some of ’em were friends of mine, I was wrong about ’em all.” The drums shuffle and shove the verses along like prison screws while the guitars bludgeon them on offbeats, and the bass drops in with the measured stomp of the hangman climbing the scaffold before the chorus explodes. It is full of death and despair and it is incredibly, shockingly alive.

Lange (who we previously saw masturbating to Dylan rehearsing – there is some weird female stuff in this movie) tries to make sure the broadcast goes through but it’s cut off. Mickey Rourke, Dad President’s right-hand man, assumes power and sends in the troops. They kick down the door of the studio and the song is shut down at gunpoint. “It’s such a sad thing to see beauty decay,” Dylan sings. “It’s sadder still to feel your heart torn away.”

Nobody’s killed, of course. Wounded but not even dead is all that’s needed to stop a poet’s honest stand. After the show, a drunk Goodman despairs (“we are living in a tawdry and vulgar age”) and tries to force the teetotaling Cruz to take a swig of his hooch. This leads to Bridges kicking Goodman’s ass, which leads to Dylan kicking Bridges’ ass, which leads to Bridges pulling a gun on both singer and promoter, clearly ready to shoot. And then Wilson, who I hate, smashes Bridges over the head with Blind Lemon Jefferson’s guitar (which really needs to replace Chekov’s gun as the metaphor for this sort of thing), beats him to the ground and stabs Bridges in the throat with the broken neck of the guitar. It is as thorough an owning as I’ve ever seen.

That doesn’t mean I still can’t be pissed that Dylan gives Wilson his own guitar and tells him to book it out the back door, willing to take the rap. This was a one-time show and Dylan’s going back to prison anyway, so why not? Damn Wilson. Lange, who’s turned out to be a true believer in her own fashion, recognizes the ruse and backs it up, fingering Dylan for a crime he didn’t commit. “He’s responsible,” she tells the soldiers who come to investigate. “It might have been a random act but I tell you what, you could put his whole life on trial.”

If your whole life was on trial, every word and every move, would you really care how bad the rest of the world is? Wouldn’t you accept prison? At least your accusers would leave you alone. The movie ends with Dylan in the back of another bus, taking him back to the can. “I was always a singer and maybe no more than that. Sometimes it’s not enough to know the meaning of things. Sometimes we have to know what things don’t mean as well,” Dylan muses in voiceover, just in case we don’t get the point. “I stopped trying to figure everything out a long time ago.” Dylan is not a particularly good actor, relying on a stone face for most of the movie, but here he shows the ghost of a smile.

And man, that pisses me off. Pretty fucking keen for you there, Bob! Going off to socially distance yourself, no band, no critics, no fans, just the way you like it, and where the fuck does that leave me? I could give a tin shit about the 60s and who killed them off but I still feel like Jeff Bridges here, impotently snarling for something I won’t get. I just want a voice and a guitar in my face and I can’t even go out to a god damn show right now, let alone one that’ll be shut down by goons. And it’s only getting worse and worse and worse. Where the fuck do you get off, Bob? Not all of us can write fanfiction about ourselves as the Christ son of America and get it on fucking film, Bob. That’s not exactly the same thing as “stopped trying to figure things out a long time ago,” Bob.

I’m listening the jukebox roll call of “Murder Most Foul” right now, it’s definitely a better list of shit than “We Didn’t Start The Fire.” It’s also a dirge and I usually embrace the transcendent and ecstatic when I listen to music, even when the ecstasy is degradation and the transcendence is to filth. The idea is to change where I am, what I’m doing, even if that change is only happening in my eardrums. More than 20 years ago, in the throes of ska-punk, I grabbed the complete Operation Ivy discography (one CD, not even an hour) and the liner notes by vocalist Jesse Michaels have been a lodestar ever since:

“Music is an indirect force for change, because it provides an anchor against human tragedy. In this sense, it works toward a reconciled world. It can also be the direct experience of change. At certain points during some shows, the reconciled world is already here.”

In 2003, the same year Masked & Anonymous was released to baffled reviews and no box office, another movie about rock and roll won over the critics and the public – Richard Linklater’s School of Rock. The movie stars Jack Black as washed-up rocker Dewey Finn, who poses as a substitute teacher to a bunch of prep school nerds and winds up forming a band with his students, first in order to get back at his old group but ultimately because he believes in the power of rock and the sound he and his young charges make.

That sound is augmented by the rest of the class working the light show and singing in the background and designing the outfits and even managing the finances. Linklater is a communitarian who loves the spark of connection between individuals and his view of rock isn’t that dissimilar from how he views baseball in Everybody Wants Some!! (named, of course, after a Van Halen song) – an area where people can come together and create something larger than themselves. Maybe something that can change the world, as Finn puts it, channeling Michaels and Operation Ivy two decades ago and a bunch of people who declared “We the people” two centuries before that.

I love that idea. It’s strong and true, and it’s a got a good beat and you can dance to it. But it’s not the only strong and true idea in the world, and what happens when you see it fail and fall under the steamroller of fear and loathing? What do you say then? I think you can only say what you feel and find that saying where it feels right. Maybe that’s through your song played hard, maybe it’s through another song that you can make your own, if just for the moment you play it. I think of Dylan singing “Dixie” – a song that planted roots and grew strong and bore strange fruit in the soil tilled by those “We the people” guys – because it has something for him, too. And recognizing and honoring that is what’s important.

School of Rock is full of great needle drops but the best comes midway through when the Ramones launch into “Bonzo Goes To Bitburg.” It’s their most overtly political song, angrily pissing on Ronald Reagan, and also one of their poppiest with a chorus full of ba-ba-ba-bas and a killer modulation (one of the band’s secret weapons) before the bridge. That’s how the song had to be and that’s how they play it, and Linklater can recognize and honor what’s right instead of plugging in the easy hit. And it’s a song with moments that are dare I say Dylanesque. “My brain is hanging upside down” would surely not bat an eye subbed into “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” And “I wish that time could go by fast, but somehow they manage to make it last” has a temporally warped echo of “I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now.” Did you know the Ramones cover “My Back Pages,” by the way?

Their cover is briefly heard in Masked & Anonymous the film, but doesn’t make the official soundtrack. That album supposedly ends with “Cold Irons Bound” but actually concludes with the “bonus track” – listed as such on the back cover – of “City of Gold,” an unreleased song from Dylan’s late 70s/early 80s Christian period covered here by the gospel stalwarts Dixie Hummingbirds. This City is a place “Where all foul forms of destruction cease / Where the mighty have fallen and there are no police,” and if that’s not a reconciled world, what is? It’s a release after the intensity of “Cold Irons Bound,” a breath after the scream, and it’s the right way to close the album.

Unlike everything else on the soundtrack, “City of Gold” does not appear in the movie. But one of the most Dylan of all Dylan songs does, even if it doesn’t make the soundtrack. At one point while Dylan and his band are rehearsing, a proud mom comes up with her 10-year-old daughter (Tinashe Kachingwe, who has become a pop singer in her own right) and says she’s taught her kid all of his songs. And the girl launches into “The Times They Are A-Changin,'” a tune that has calcified, ossified, petrified as a Song of the 60s. Kachingwe sings it like a song she’s had to learn and that’s what makes it interesting – there’s no baggage other than a pushy mom behind this, and her voice is clear and true. Kachingwe might not understand where the song comes from but she knows it and performs it well. And Dylan respects very little in the movie but he respects this, someone singing a song of his and not making it about him. If anything unifies the soundtrack, it’s this – taking Dylan’s songs and finding new and personal things in them, not taking what they mean for granted.

The worst part of “Blowin’ In The Wind” when sung badly is its certainty, its self-satisfaction. The smugness of knowing that someone else is wrong, of asking a question with no right answers. That is there in the song, but there is a larger lament to be heard, one that Dylan is singing at the end of the movie, when a live version from 2001 plays over the final images and the end credits. It’s not about the questioner, but the sadness of the questions. Kachingwe finds this through innocence, Dylan through experience. The questions he asks and the riddles he poses have always existed, but how they’re asked – that they’re asked – is still important. As for the answers? Well, we know where they are. And the answers I want from Dylan are in the same place. I can ask and he’ll whistle Dixie. It’s not his job to answer what I want.

At least the questions stick around and poke and prod and even give comfort in the asking. I spin the soundtrack, finding sadness and anger and joy and incomprehensibility, something new if I really listen and a respite for my pounding head if I don’t. What’s going on outside won’t stop anytime soon. I can always play the album again – he can make the movie, and I can find value there, but I can still choose the songs over it. Figure out that, Bob.

The rendition of “Cold Irons Bound” that burns a hole through Masked & Anonymous cuts out a few lyrics from the album version, including, ironically, a couplet about endurance: “Some things last longer than you think they will / There are some kind of things you can never kill.” In this unreconciled world, maybe that’s the only hope we have.