One: Start with the work.

Don’t kick things off with your thoughts on the state of the blockbuster, or a personal anecdote about your father, or your personal politics, or the best advice you ever got. If you put Batman in your headline, then your audience is here to read about Batman. It’s easier to convince someone of your idea if you start with something you both share, which in this case is the experience of the work; if you start with the fact that Batman is a rich man who beats up petty criminals, people can at least see the leap to “Batman is a fascist” or “my father imprinted upon me a sense of doing the right thing, even at personal inconvenience”. People will roll with just about anything in an essay so long as the ‘anything’ comes in the middle. It also just makes it easier to write – when you have about five different equally interesting points to choose from, it’s so much simpler to start with the work overall and zoom in. It’s to the point where my process now begins with trying to summarise the entire work in one sentence, which forces me to elaborate, which leads to me veering off.

Two: Be honest.

There are two meanings to this that tie together. When writing for public consumption, it can be tempting to censor yourself, whether that means actively writing what you think your audience wants to hear or passively choosing not to reveal your true feelings on the work. This produces writing that’s satisfying to neither write nor read; criticism is about seeking a fundamental truth, so beginning the process with a lie will inevitably lead to failure. If something moves you, it’s because there’s something there to move you; chasing and uncovering it is always useful and, perhaps, could be of use to someone else (the way I looked for a fundamental truth in a video game about chainsawing aliens in half). The second meaning is that you must be honest about the facts and the way they interact with or even fight against your reaction; it was tempting to go through the MCU deliberately ignoring everything I found interesting and dismissing the whole project as complete crap, but it was more interesting to try and take it on its own terms as well as my own, and I feel my criticisms of it were more effective because of it. To put it a simpler way: start with emotion, then filter it through reason.

Three: Structure is unnecessary.

I’ve tried a few different structural tricks and never been satisfied with the results. I’m sure there are ways to get it to work, but a stream-of-consciousness flow of ideas is always more satisfying to me to write – start at the start, write down your ideas, and then stop. The only two structural tricks I’ve consistently found useful are parentheticals between paragraphs and line breaks when I have no idea how to connect two thoughts.

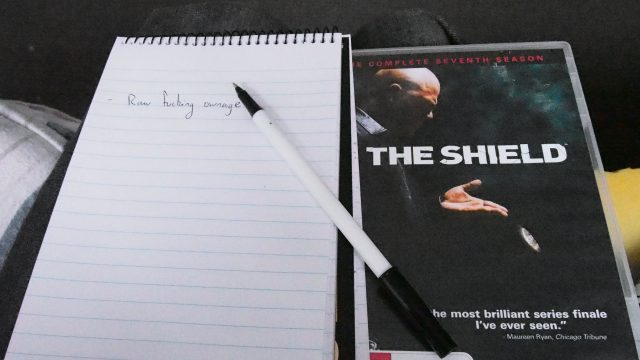

Four: There is no output without input.

I’ve been gradually running out of the essays I always wanted to write, which has forced me to pick up fresh material to churn out more essays, and it’s been thrilling and delightful, forcing me out of a rut of rewatching the same old shows and movies – Year Of The Month has been fun because it’s both freeform and limited enough to constantly force me out of my comfort zone and into trying new things, testing theories in wildly unpredictable contexts and either confirming or refining them. Criticism is observation, and the more that is observed, the better the observations become, particularly since my essays have sufficiently wide scope on each individual work that I often feel as if I’ve said the last word on it. To keep up a weekly pace on essays means not just voraciously consuming media, but consuming a wide variety of it.

Five: Don’t leave it until the last goddamned minute

Sometimes I write it in my head over the week and it all comes splurging out over the weekend, and that’s fine. Putting off thinking about it at all until the last minute is about as effective as it was in college.