In so much of the popular imagination, especially among people of a certain age, Lyle Lovett is probably still best known as “that guy Julia Roberts married despite his face.” That’s a shame, because Lovett’s unique brand of bittersweet folk-rock country-fusion is one of a kind, making him a standout even among that set of beloved-in-state Texas singer/songwriters, and The Road to Ensenada is my favorite work of his, showcasing great storytelling and stylistic diversity ranging from ballads to laid-back country tunes to tearjerkers to just plain rollicking good times.

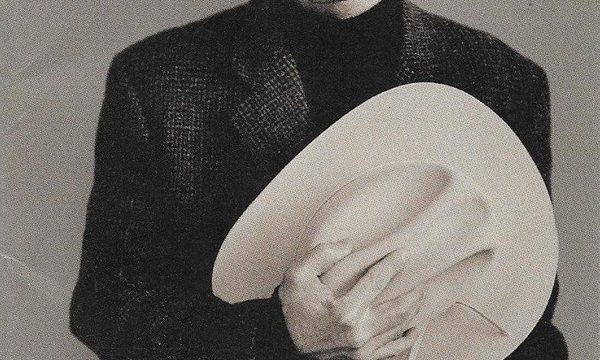

We kick off with a track that showcases Lovett’s sense of humor, detailing his love of his Stetson and addressing a guy who’s been eyeing him, in its chorus– “You can have my girl, but don’t touch my hat.” (I was very surprised to learn that “Don’t Touch My Hat” was never used on Justified.) It’s an easy, mellow, welcoming introduction to the album, before we get into the terrific “Her First Mistake,” an energetic ballad about a guy at a bar trying to pick up a southern gal. It’s a great showcase for both Lovett’s gift for storytelling and for the music meeting the lyrics, as the verse narration is pretty quiet, before a crescendoing “Come on, baby” refrain leads us into the energetic choruses where Lovett’s smooth talker makes his move (or tries to get over letdown– “I don’t know just what you heard / ‘Bartender, set ’em up’ are my favorite words” might be my favorite moment in the song).

The tearjerker is “I Can’t Love You Anymore,” Lovett’s perspective on an emotionally trying breakup (perhaps with Roberts, if the opening lines are any indicator). It’s simple and straightforward, but so sincere and heartfelt on Lovett’s part that it really works, in part due to that stunner of a couplet in the chorus: “‘Cause I don’t love you any less / But I can’t love you anymore.”

A couple of other songs I really like: “Private Conversation,” a song about broken hearts and broken relationships, clandestine affairs, and keeping secrets. I dig it for its up-tempo vibe and how it contrasts with the lyrics, and that lesson of a verse that hits hard:

And the moral of this story

Is I guess it’s easier said than done

Ohh look at what you’ve been through

And to see what you’ve become

There’s also “Fiona,” a tale of a woman on the bayou, strong and dangerous to those who cross her– a more straightforward example of Lovett’s tunesmithing in the country/folk vein. There’s a cover, too: “Long Tall Texan,” written by Henry Strzelecki (part of The Nashville A-Team) in the 1950s. The stomping style of the song is a change of pace for the album; Lovett is also joined on vocals here by none other than Randy Newman.

The highlight of the album is the fourth track, “That’s Right (You’re Not From Texas),” a rollicking good time where the singer gently teases the subject for their affectations (“You think you pull your boots on right / And wear your hat so well”) before reaffirming them in the chorus (“That’s right, you’re not from Texas / But Texas wants you anyway”)– the music even changes tempo between verse and chorus to highlight the contrast.

The breadth of Lovett’s influences are perhaps more present in this song than any other: up-tempo swing in the guitar, fiddle and gospel-style choirs and leads rounding it out; the entire third verse is a tribute to Uncle Walt’s Band, a South Carolina-based Americana group that moved to Texas and found local acclaim in the 70s and 80s, being one of Lovett’s favorite bands during his college years. (Sadly, Walter Hyatt died in a plane crash just a month before this album was released.)

Further verses elaborate on Lovett’s love of Texas; the last two highlight the people and how welcoming they are– not only are the women beautiful “and their men will buy your beer for free,” Lovett offers his help to the subject of the song and encouragement, leading into the final chorus: “The next time somebody laughs at you / You just tell ’em you’re not from Texas … But Texas wants you anyway.” Lovett’s vision of Texas is one where the people know how to have a good time and are welcoming to any visitors and newcomers who want to adopt the state as their own.

(For the record, parts of the second and third verse seem to reference Lovett’s now-ended relationship with Roberts– “Though my girl comes from down in Georgia” and “She grew smaller in my mirror / As I watched her wave goodbye.”)

Texas is unique in the cultural imagination on several levels– there’s the stereotypes of cowboys and shitkickers in the popular consciousness; the over-the-top affectations of outsiders who adopt Texas as their home; and the sincerity and rich depth of understanding of the history and culture possessed by people like Lovett, whose love for Texas bursts from this song not only in the lyrics but in the musical influences as well. Texas isn’t just a state of cattle and oil and country music; there’s a rich and varied musical tradition there, a tremendous cultural history driven not only by the touchstones of popular imagination, but also by the Mexican cultural influence, as well as the German immigrants of the 1800s, whose traditions remain alive and well in the Hill Country– even if Shiner Bock isn’t what it used to be, it’s hard to find a better Oktoberfest in America. (And, hell, maybe even a bit of the hippiedom of old Austin still pokes through from time to time.)

The Road to Ensenada manages to represent both the rich history, culture, and music of the state, and Lovett’s own personal love for it, and perhaps that’s why it endures. Give it a listen and you might understand why Texas wants you anyway.