Fritz Lang was an incredibly versatile filmmaker, but he spent much of his career in both Berlin and Hollywood finding striking images in relatively modest crime dramas — the Dr. Mabuse series, Spies, M, Fury, The Big Heat. Metropolis, his greatest and, by a large margin, most famous film, stands as an outlier. Because when I say “great,” I just don’t mean in quality — I mean in scale too.

Lang set out to make “the costliest and most ambitious picture ever.” That wasn’t an uncommon goal at the time. Every other movie out of Hollywood was some kind of epic, arraying jaw-droppingly huge crowds in front of jaw-droppingly huge sets, so expensive that they could run at a loss even though everybody and their mother went to see them.

But money can’t buy you legacy, and while the best of these films have lost none of their power — if anything they look even more spectacular now that we’re used to sets and crowds that only exist in a server bank — they’re almost totally forgotten today. Even the few that still receive acclaim thanks to the personalities of auteurs like Erich Von Stroheim aren’t likely to show up in your average film survey course, crowded out by the simpler efforts of the silent clowns and Metropolis’ German-Expressionist predecessors.

Von Stroheim offers a perfect example of the milieu Lang was working in. He spared no expense, most notably in Foolish Wives, where he famously built a life-size replica of Monte Carlo on the Universal backlot and insisted they shell out for real caviar instead of the usual raspberry jam. So it was pretty hilarious after learning that story to see that Von Stroheim obviously spared some expense, since the very next shot is a plot-relevant story hastily pasted onto an off-the-rack newspaper.

Despite his ambitions, Lang didn’t quite have Universal money, but he knew how to stretch what he had. Long after all the hundred-foot behemoths built in Hollywood have been forgotten by everyone except a small coterie of silent-film fans, Metropolis’ miniatures and matte paintings have become icons, reappearing in dozens if not hundreds of later science fiction movies and illustrations.

It doesn’t hurt that it’s sometimes impossible to tell they are miniatures, thanks to Eugen Schuftan and his “Schuftan Process.” While most films before and after Metropolis used dodgy rear-projection and post-production “matting” to place actors in settings where they obviously never actually went, Schuftan put them all to shame with the lowest possible tech: mirrors. Even now that nearly all movies use bleeding-edge computer technology to create their settings, almost nothing looks as seamless as this century-old film. The only way to spot Schuftan’s trickery in the early scene at the stadium is to watch obsessively for the slight shimmer where the life-sized set meets the miniature. Other scenes are downright mind-bending as clearly real actors run across clearly fake miniature streets.

I have no idea why so few other films have used this effect when the results are so close to flawless. It may have been prohibitively expensive, though my romantic side likes to imagine it was some ancient wisdom that’s been lost forever. Nearly all of the effects in Metropolis haven’t aged a day in the past hundred years — except, weirdly enough, for the one that’s most often excerpted, of the Machinen-Mensch transforming into Maria’s likeness through a cheesy dissolve effect. The faces don’t even line up! Apparently, the process involves moving the robot’s eyes a good couple inches down its face.

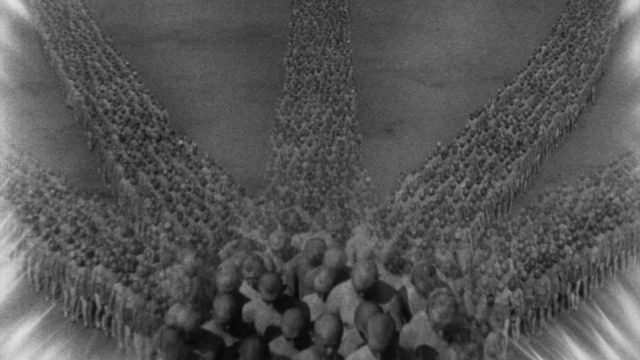

While none of his contemporaries touch Lang in the effects department, Lang more than keeps up with the Hollywood cast-of-thousands spectaculars. He doesn’t just make the undistinguished mass of workers awe-inspiring, he uses it to develop his story’s themes about the dehumanization of labor and the danger of mob mentality. The same goes for the jaw-droppingly huge (or seemingly huge) sets, creating a dystopia where man has become a speck dwarfed by his own creations.

Lang even takes a few minutes off from his science fiction story to prove he can handle a Cecil B. DeMille-style biblical epic when Maria gives a very loose retelling of “the Legend of Babel” (it’s hard to imagine that the architects punished for their blasphemous hubris would ever decorate their tower with a message that begins “Great is God” even if it goes on to suggest man is equally great). Lang combines the wow factor of Hollywood’s enormous crowd scenes with simpler but equally awe-inspiring visual tricks when he mirrors the march of slave laborers into five lines converging in the center of the screen. When I saw this on the big(gish) screen for my German Film class, my jaw stayed slack almost the whole two and a half hours, even as I heard sleepy noises from the seats around me. I felt a little Pauline Kael in her famous review of Shoeshine — how jaded must you be for this not to keep you on the edge of your seat?

So how did Lang get such a huge blank check? Because the last time his bosses at Ufa wrote him one for his Die Niebelunegen duology, it paid off enormously. It’s funny to think now that Niebelungen was a hit while Metropolis bombed. A century later, Metropolis is one of the four or five silent movies everyone knows, and Die Niebelungen’s only familiar to people who can name somewhere between fifty and a hundred. Even with Lang’s talent, money still can’t buy you legacy.

Watching Die Niebelungen now, it’s not hard to see why. The effects certainly aren’t up to par: Lang complained that it took weeks of work to get the life-sized dragon its hero Siegfried slays near the beginning not to “move like an old man,” and I don’t think he ever quite succeeded. It doesn’t help that the supposedly fearsome monster looks more like a placid herbivorous dinosaur than anything that might send kids hiding under their seats.

Lang and screenwriter Thea Von Harbou followed the anachronistic example of the original Niebelungenlied epic, which Wagner’s more famous version notably ignored. I can see it working in verse, but in a visual medium, it’s hard to shake the impression the characters are time-traveling between scenes, from the distant past of pagan mythology to the obviously post-Christian city of Worms (seriously, there’s crosses everywhere) and back to Ancient Rome when Atilla the Hun — yes, that one — enters the plot. Some versions Germanize his name to “Etzel,” but he’s a Hunnish king who attacks Rome, who else could he be?

Making the Huns the nominal villains of the second part, Kriemhild’s Revenge, is certainly an odd choice, given how universally slurred Germans were with that name during the still-recent World War. But Lang’s Huns are everything but Germanic, drawing from every “inferior” culture from Native Americans to Imperial China. That prejudice would resurface in Metropolis, where the local den of sin has the distinctly Japanese name “Yoshiwara” and gets introduced with a montage of hideous ethnic stereotypes. Unlike ISIS though, you do have to hand it to them: the sets in the Hunnish city are gloriously grotesque, and their designer Heinrich Umlauff rightly gets a separate credit.

The exotically evil Huns get at the fatal flaw of Die Niebelungen: it’s impossible to fully enjoy two movies that open with a dedication “to the German people” knowing where that rabid nationalism would lead. Worse, Lang and Von Harbou can’t even make a persuasive case for their ideology. Remember how I called the Huns “nominal villains?” That’s because the nominally heroic Germans come off even worse.

The Revenge of the title is for the German Hagen’s murder of Siegfried in the first film. (As for Brunhild, who egged him on, she’s apparently exempt from Kriemhild’s revenge, since she’s either totally absent from the second film or close enough for me to think she was.) His brothers refuse to let him face justice, even after he murders a baby right in front of them. “You underestimate the loyalty of the German people!” one of them says, apparently expecting us to find loyalty to a baby-killing bastard admirable.

But it’s all worth it to watch Margarete Schön as Kriemhild. There’s never been a better fusion of costume, makeup, and performance. The heavy shadows drawing attention to her piercing, pale eyes and long, regal robe enhance Schön’s unbending stone-straight posture and unchanging expression of ice-cold fury through all the carnage she oversees all create an image that burns its way into your consciousness.

Continued tomorrow