The Spanish painter Francisco de Goya lived and worked in the middle of a shift in the art world. The Enlightenment was spreading into painting, with the work of the Neoclassical school presenting itself as the new ideal of rational art. But by the time Goya began work on his Caprichos, the backlash was beginning to spread as well, represented by Romantic artists like Henry Fuseli and William Blake. Goya was well-known as a friend of Enlightenment intellectuals like Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, and as a student of Anton Raphael Mengs, a major player in the founding of the new Enlightenment school of Neoclassical art. As a result, the prints are often identified as a satire of superstition and other counter-Enlightenment ideals, a “correction of human vices and errors.” And yet, at the same time Goya revels in the superstitious fantasy and unenlightened darkness he portrays, creating a work of both Enlightenment reason and Romantic imagination. Rejecting “enlightened” Neoclassical ideals in favor of a dark, fantastical portrayal of the Sublime, Goya shows his deeply complicated allegiance to the Enlightenment.

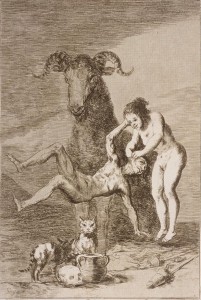

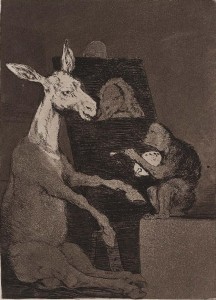

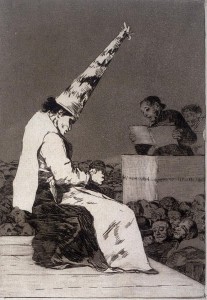

The best way to understand Los Caprichos would be to begin at the beginning, that is, with the title. Goya’s decision to title his prints Los Caprichos turns out to be the best argument both for and against the work an Enlightenment piece. The word can be translated, just to start with, as “caprice,” “whimsy,” “whim,” or “fancy.” If we interpret the title as a reference to Goya’s Enlightenment message, the prints are an indictment of the foolish whims, or “eccentricities and errors” of contemporary Spain. And that’s a fair enough assessment. Goya’s subjects include common superstitions, unenlightened parenting, the ridiculousness of the capricious elite, the whims of the Inquisition, quack doctors, and gluttonous friars. The fantastic subjects of witches and demons, in this interpretation, are the fancies of the credulous masses, and in visualizing them, Goya makes their silliness plain. On the other hand, Goya could be describing his own creative process for the series, portraying it as a works of imaginative fancy. By this interpretation, rather than mocking the images of unearthly and unholy creatures, Goya is celebrating them, letting Spanish tradition be his launching point for his works of grotesque and personal fantasy. And indeed, it is hard to see Goya’s portrayal of folk beliefs coming from an entirely superior position. He is too invested in it for that, drawing deep from the wells of his own thought to create unheard-of images like the woman-headed hen devoured by lion-faced judges in or the moody, atmospheric covens of half-animal witches. The demonic goat that looms over “Ensayos” makes it hard to believe Goya does not believe, at least on some level, in the power of such superstitious or mystical beliefs.

At one point, Goya considered calling the prints Sueños, or dreams. This title may give us some insight into the nature of the series, but it too goes both ways. On the face of it, dreams seem to be purely the realm of the Romantic artist. Blake and Fuseli portray dreams as a place of pure inspiration, as a vehicle for the impossible and sublime images of paintings like “The Nightmare.” Surely, nothing could be further from Enlightenment rationality than material taken from the unconscious and irrational world of dreams. But the dream had also been a traditional vehicle for satire in Goya’s time. Many of his fantastical images can be explained away by their value in communicating Goya’s fundamentally rational satirical points. The witches and hobgoblins are stand-ins for the clergy and other bad teachers, uniting them closely with the darkness of superstition. The Gothic grotesquerie, so far from the rationalist idealism of artists like Jacques-Louis David, is used in service of similar goals, to make unenlightened institutions look more ridiculous. And yet, Goya seems so fascinated by the bleakness and strangeness of his subjects that we may wonder where his interest truly lies.

The Neoclassical movement promoted Enlightenment concepts by focusing on the ideal and the beautiful. Goya takes a very different approach here that unites him more closely with the Romantics. Los Caprichos is a neverending parade of social ills and nightmares, never lightened by any explicitly positive message. Goya does not let these horrors pass totally unmediated; his captions make it quite clear that the viewer is supposed to reject them. But he also rejected the heavy-handed didacticism of the French Enlightenment, veiling his morals in sly sarcasm and ambiguity. A satire of flattery in portrait art is titled “Ni mas ni menos” (“Neither more nor less”). His assessment that the young woman’s life in “Por Que Fue Sensible” “could end in no other way” is a great contrast with the sympathy with which Goya draws her. His only commentary on his “Muchachos al avío” (Lads Making Ready) is “Their faces and clothes make it clear what they are”.

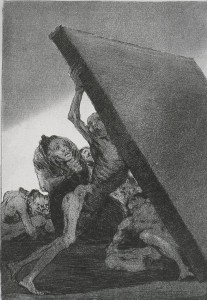

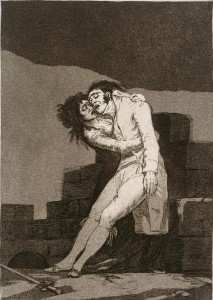

He also shows far less interest than an artist like David in classical beauty. His grotesque figures are obviously quite far from the golden ratios of Greek art, and so too is his subject matter. Goya is obviously more concerned with Romantic sublimity than Classical beauty. There’s hardly a traditionally beautiful or pleasant moment in Los Caprichos. They are all about ugliness and starkness, terror and pain, the elements of the Sublime. But the difference in approach is even more significant. Neoclassicism is based on a system of rational, scientific rules; Romanticism is based on the rejection of all rules in favor of individualism. On this count, Goya is firmly on the side of the Romantics: “I will give a proof,” he said in his address to the Royal Academy of San Fernando, “that there are no rules in Painting, and that the oppression, or servile obligation of making all study or follow the same path is a great impediment to the Young who profess this very difficult art.” Compare David’s rendering of a fairly sublime subject, the death of the revolutionary hero Marat, in comparison to Goya’s “El amor y la muerte”.

Marat’s pain is less important than his nobility. His face is contorted, but not too much, and his limp arm is still beautifully muscled. The use of parallel lines and negative space ensures the canvas is fundamentally calm. In contrast, the man and woman’s faces in “El amor y la muerte” are hideously distorted, in emotional and physical pain. Their askew posture and the dark, irregularly shaped cloud over their heads give the print a queasy sense of disorder. Clarity is essential to the Neoclassical style: clear, ordered, and most of all, well-lit compositions. Los Caprichos were revolutionary for Goya’s use of aquatint etching, which he uses to create murky, mysterious shadows, that cloak his figures from rational perception. The easiest comparison here is not the noble chiaroscuro of the Neoclassicists, but the airy, irrational darkness of Fuseli.

The Romantics reveled in unpleasant subjects that viewers could experience from a safely vicarious position; the rational art of the Neoclassicists provided heroic subjects that the viewer could inspire viewers as they went about their lives. Though Los Caprichos have the moralistic intent of such pieces as The Death of Marat, Goya communicates those lessons through a very Romantic obsession with the worst of both reality and imagination. Noble men and beautiful women are present, but only so that injustice may be visited on them, or so that we can see their descent into corruption. Is the young man in “Amor y muerte” a noble martyr like Marat that viewers should emulate? No, he is a cautionary tale, killed by his own foolish passion in a duel. Los Caprichos is a fundamentally negative work, in the sense that it teaches by giving examples of what not to do. This allows Goya to indulge his fascination with the Sublime, and leaves open the question of whether he is condemning the darkness of an unenlightened world or celebrating his own dark imagination. Certainly, the wild and original invention of the pieces suggests the latter. This is a major difference between the climate of France and Spain: Goya’s earlier work had shown the same morbidity in his portrayals of prisoners and madmen, but these were part of a wider vogue for the subject matter. And yet what he does in Los Caprichos is entirely his own.

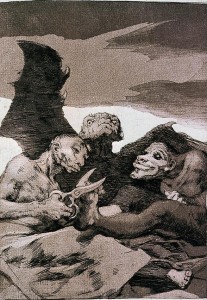

There may be an even darker motivation for Goya’s focus on the worst of humanity. A major assumption of Enlightenment thinkers like Rousseau was that mankind could be perfected, if only society could mold it in a more profitable direction. Goya believes this, to an extent: for instance, he captions Plate 5, “Tal para qual,” “the vices of one and the other come from bad upbringing”. The prevalence of bad influence is certainly important to Los Caprichos, portraying Spain as a society that turns its children into monsters. Goya’s worst criticism is reserved for authority figures corrupting their followers, while the followers’ sins themselves are treated with great empathy, as in the pathos of “El amor y la muerte.” Education is a recurring theme, with the focus of a witch and a young woman on a broomstick being Goya’s sarcastic estimation of the hag as a “Linda maestra,” or lovely teacher. In “Si quebro el Cantaro,” Goya asks, “The son is mischievous and the mother bad tempered. Which is worse?” But the gruesomely sadistic look on the face of the mother makes it clear what the answer is. From this, we may infer that all we need to do is remove these negative influences and humanity will ascend to the ranks of the angels. And yet, the hopelessness of Goya’s work puts this idea in doubt. Humanity is certainly not the noblest of creatures in Los Caprichos, but a race of monsters, all gnashing teeth and flaring eyes. Often, human foibles are characterized by subhuman figures, like the lion-faced men of “Qual la descanonan!” or the bird-faced and goat-legged witches.

Perhaps this is Goya’s way of absolving human nature of such vices by showing them as unnatural. But if so, there is scarcely a human being in the pages of Los Caprichos, suggesting that the Enlightenment goals of the perfect man are so far out of reach as to be impossible. The achievement of such goals is never present in Los Caprichos, and it may not have a place. I said that Goya fills his series with bad examples, and never offers any paragon for viewers to follow in their place. Maybe that is because he is portraying a world where a good man is beyond the reach even of his imagination. The darkest and most fantastic of these prints suggest that there is a more-than-human influence on human evil. Like Blake or Coleridge, he deals with the dark forces beyond our control and understanding, the winged creatures and glowing eyes in the dark.

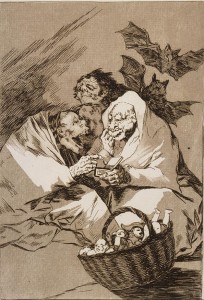

This brings Goya up against another central tenet of the Enlightenment. The period was a golden age of scientific discovery, because its leaders believed that everything that need be known could be discovered through experience. The methodology of empiricism became more and more important, in the belief that nothing that could not be proven could be believed, or that it needed to. The reality of the Enlightenment thinkers is a fundamentally understandable place. Goya is not so sure. Surely, if experience can be trusted, we know nothing better than our own selves. But Goya suggests instead that “Nadie se conoce:” “Nobody knows himself.” Masks are everywhere in Los Caprichos, hiding subjects’ true natures from the world. In her biography of the artist, Sarah Symmons points out that masquerade had been an obsession of Goya’s for many years before this, appearing frequently in his sketchbooks. But then, masks can be taken off. “A monocle is not enough,” Goya says in his commentary on Plate 7. “Judgment and experience of the world are needed.” That still leaves the question of how well the world can be experienced. Goya’s skillful aquatint style makes that doubtful, as he cloaks everything in dark shadows. Though it may not necessarily be Goya’s intention, the prints certainly create an impression that the obscurity of the world is too deep to be pierced by any enlightenment. Los Caprichos are fascinated with the world of superstition, and maybe that’s just so Goya can expose its stupidity. But he makes that kind of magical and mysterious world strangely seductive. The ghouls and spirits of the prints are fascinating in their grotesquerie, and in the absence of heroic Enlightened figures, they dominate the universe of the prints. Rather than encouraging viewers to laugh off their childish fears, characters like those in “Mucho hay que chupar” and “Se repulen” seem more frightening than ever under Goya’s pen.

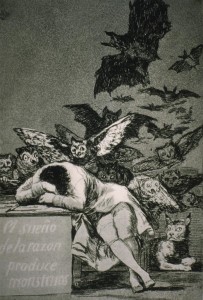

The best way to figure out just where Goya stands is to take a close look at the most famous of his prints: “The sleep of reason produces monsters.” The standard interpretation is one that seems perfectly in line with Enlightenment dogma: while rational natures sleep, the world fills with monstrous horrors. The assumption is that once reason is awoken, the monsters will be banished. In “Goya’s Enlightenment Protagonist-A Quixotic Dreamer Of Reason,” John J. Cialfo suggests that the title should be translated “the dream of reason produces monsters.” That is, reason is nothing but a foolish dream, impractical and possibly dangerous. While his reading would put Goya firmly in line with the Romantics, I think the answer lies somewhere nearer to the middle. “Imagination abandoned by reason,” in Goya’s commentary, “produces impossible monsters: united with her, she is the mother of arts and the source of their wonders.” Goya may have originally intended the print as a frontispiece for the book as a whole. As it stands now, this plate is a transition point, a gateway as it were to the book’s most fantastical section. Even though I have argued that the superstitious nature of prints like these are more seductive than the promise of a reasonable solution, Goya does not see it as a case of either or. He is letting his imagination run wild, into dark corners of the irrational world, but it’s always united with reason. Unlike some Romantic art, these flights of fancy are not an end in themselves, though they succeed spectacularly by that standard. He is channeling their strangeness in the service of promoting reason. One could argue whether they are not quite as successful in that goal. Sometimes his rational, didactic commentary seems like a fig leaf for unbridled imagination. For instance, “Mala noche” is a transcendently sublime scene, full of darkness and irrational fear. Goya’s commentary, “Gadabout girls who don’t want to stay at home, risk exposing themselves to these hardships”seems barely related to the image it accompanies. It has the air of a tacked-on message, adding little to the print. Its attempt at left-brain edification cannot overcome the powerful right-brain emotional appeal of Goya’s image.

Both sides, however, are essential to “The sleep of reason.” The artist in the plate is surrounded by dark, menacing figures of owls and bats, the symbols of ignorance and superstition. But among them is another creature, with an entirely different meaning: the white-eyed lynx of sight. Its presence here implies that not only does imagination need reason to create wonders, reason also needs fantasy to see the real world clearly. The artist in the print, often interpreted as Goya himself, sleeps uncomfortably, burying his face in his hands, which suggests he is hiding from the apparitions that surround him. He seems to be avoiding the horrific world around him: perhaps this is Goya’s commentary on more traditional rationalist art, which forsakes the ugliness of reality and the terrors of fantasy in favor of idealized, “rational” fantasies. One of the owls is trying to prod him awake, possibly so that reason can awake to give the fantasy meaning. These two figures show a symbiotic relationship between el razon and la fantasia. While reason is avoiding the specters of superstition, it needs instead to confront them, so that it can expose its faults and shape it into something more worthwhile. The prints that follow show what this process produces: sublime works of art that powerfully convey important messages to the reason of their viewers.

So it turns out that Goya does not belong fully to either the Neoclassical Enlightenment or the Romantic Counter-Enlightenment. While rejecting the rigid rules of Enlightenment art and questioning its belief in empiricism and the goodness of humanity, Goya still embraces the call to bring reason to the world. But he does this in a synthesis with Romantic ideals, embracing superstition even as he exposes it, using his dark imagination to promote the light of rational truth. Goya, like the greatest artists, does not fit easily into a box. He draws from his provincial background and his Enlightenment education. He delves into the depths of nightmare fantasy and of harsh reality. The world is complicated, and cannot be fully explained by either reason or emotion. In order to reflect it, Goya created a secondary world that is every bit as complicated. Perhaps that is why his vision is so enduring.