Pictured: Igor Stravinsky (l.) and Elliott Carter

The ideal has many names, and beauty is but one of them. (Somerset Maugham)

As terms defining periods, “modernity” usually gets applied to history (starting more or less with World War One) and “modernism” gets applied to art. A good working definition of the latter: one more turn in the tradition that breaks the tradition. In 1956, Willem de Kooning gave a good sense of this ideal when he said

every so often, a painter has to destroy painting. Cézanne did it, Picasso did it with cubism. Then Pollock did it. He busted our idea of a picture all to hell. Then there could be new paintings again.

Half of modernism is in these lines, the sense of clearing away the past, making a new ground for art to happen. Its works are confrontational, provocative, and some of them (like Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring) even got their own riot. One way of understanding modernism is to recognize that there’s no agreed meaning for “postmodernism”; how do you define an art when its rules–its tradition–has been blown up? The other half of modernism, implied not in de Kooning’s words but in his examples: the modernists come from tradition but are not in tradition. de Kooning, Cézanne, Picasso, Pollock were none of them outsiders, all of them classically trained, and their work all shows a clear evolution from those classical techniques (de Kooning’s early drawings are stunningly realistic) to their transformative mature works. Arnold Schönberg, who created one of the founding points of modernism with his twelve-tone system, said “I credit myself with having written truly new music which being based on tradition is destined to become tradition.” Except for that last part, he was right; and “except for that last part” makes all the difference.

Tradition makes the distinction between the modern and the avant-garde. Avant-garde works handle tradition by ignoring it; they run right over some of the rules of art and blindly follow others. John Cage (who studied with Schönberg) stands as the great figure of the avant-garde, jumping from music to painting to poetry to sculpture to theater to dance and landing in cinema, composing works by chance, working with a great rigor but only with his own rules. Modernists much more consciously learn the rules and the tradition, and deliberately reject them in order to advance them. Born from tradition, and taking it to the point where tradition can be no more: that’s modernism.

Composer Elliott Carter, who was born at the end of Teddy Roosevelt’s administration and died the day before Barack Obama’s reelection, embodied modernism perhaps more than any other contemporary figure and certainly outlasted all of them, composing right past his hundredth year. Deeply theoretical within the rules of classical music, uncompromising and uncompromised towards any audience and with a shit-ton of ownage along the way, his music was the last glory of a particular moment now gone, the last inheritor of the great, confrontational works of Stravinsky, Picasso, and James Joyce.

Carter makes a good subject for a discussion of a broad trend in art because it’s easier or at least more justifiable to talk about tradition in classical music than in any other art form. Music depends on performance in a way that painting and writing (and even drama) don’t; scores can be published like scripts, but until the 20th century, if music isn’t performed it doesn’t exist. (No surprise that so much experimental work has, historically, been written for piano, classical music’s favorite solo instrument.) Getting performed automatically brings in dimensions of politics and tradition, of what people have been trained to perform and what they will accept performing; two classics of 20th-century music, Edgard Varèse’s Ionization and Kryzstzof Penderecki’s Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima, suffered from either poor performances or ensembles refusing to perform them. (The development of new traditions in performance in modern music has been the subject of another shelf of books.) Carter began writing music in the 1930s, and to write classical music in that period automatically bound one to a tradition, its resources and limitations.

Carter’s first decade or two of music doesn’t veer too far from that tradition, it’s interesting but not shocking. A good point of reference would be Paul Hindemith in Germany, someone who was seeking to expand ideas of tonality from the past into the present rather than overthrow them. Carter’s early compositions (including some good, memorable choral works written for the Harvard Glee Club) stay within the traditional classical grammar of key signatures, preparation and resolution, and counterpoint (much of the latter he learned from Nadia Boulanger in Paris, one of the century’s great teachers of American composers. The range of her students include Carter, Aaron Copland, and Philip Glass) with a freer-than-usual approach to rhythm the only hint of what was to come.

What was present from the beginning of his work and continued to the end was his sense the role of an American composer. Carter sought, as much as possible, to be a professional composer, working within strictly defined institutions and seeking to strengthen those institutions. He came from the wealthy, old New York class (his family was rich two generations before Carter) and had its sense of entitlement and duty. Beginning with his education at the Horace Mann School and Harvard (Carter claims never to have missed a performance of the Boston Symphony Orchestra), Carter made the connections and joined the organizations as a man rising in a profession. Arranging national anthems for the Office of War Information in World War 2, editing journals like the benchmark Perspectives of New Music, setting up tours for American musicians in Communist countries, working as a member of the League of Composers, composing occasional pieces for festivals, campaigning for funding, writing articles about other works of music and the role of the American composer, and receiving (lots and lots of) honors: all the work of a man who lived composing as a career, not a calling, and wanted it to remain that way. You just can’t imagine him driving a cab, taking a job as a plumber, or working with rock musicians (as Philip Glass did), riding the trains during the Depression (like Harry Partch), breaking into all sorts of other arts (like John Cage), or getting into political trouble the 1930s and simply walking away from America, taking up residence in Mexico City, and creating an entire body of work on his own (that would be Conlon Nancarrow. Almost all of his work is for player piano, and his aesthetic is close to Carter’s even if his life isn’t–Carter quotes Nancarrow in his First String Quartet). Carter lived a tradition of a composer as a well-supported national figure, and a tradition of the arts as central to the life of a nation, and he was one of the last to do so.

Among composers, it’s most revealing to compare Carter to Charles Ives. Ives was another nonprofessional composer (he worked all his life for his father’s insurance company); he’s also the arguably the beginning of modernism in American music. (His composition The Unanswered Question counts as another founding point of modernism.) Relentlessly innovative, crafting music with layers on layers of hymns and marches and sounds from his childhood, exploring quarter-tone (24 notes to the octave rather than the usual 12), loading pieces with polyrhythms and polytonality, promiscuously mixing styles from the history of classical music, revising his pieces to make them ever more dense and complicated (and difficult to play–his Fourth Symphony required three conductors), he was an avant-garde artist in the American frontier tradition. Ives constantly explored, occasionally explained, and never theorized.

Carter began his career as Ives was ending his; they corresponded, Ives introduced him to much of contemporary musical life in New York, and Carter worked on publishing some of Ives’ music. The two of them make a near perfect case study for Harold Bloom’s anxiety-of-influence theory: every great poet comes from a “strong misreading” of an earlier one. (For a more musical and contemporary analogy, think of Carter as Lou Reed to Ives’ David Bowie.) Carter theorized and calculated what Ives did instinctively, almost by improvisation. Ives referred to his layering as “rhapsodic informal counterpoint” and informal is about the last thing Carter could ever be. Ives’ music contains literally hundreds of references to earlier music; Carter’s has nearly none, fitting right into the modernist ideal of “make it new.” If the American avant-garde takes as its model the exploration of the frontier, finding a new place, clearing the ground, making a few maps, Carter’s music is of the city that grows there generations later, planned out, complex, rigorous–you can hear this especially in his 1955 Variations for Orchestra, which sounds like a more precise version of Ives.

There’s no way around the fact that the tradition of classical music in Europe has roughly a half-millennium jump on that in America; in Carter’s words, America had classical music for “only 200 years, and only during the last 100 have we attained professional status.” His professional development into a composer meant, by definition, that he was learning a European tradition from the beginning–he attended the American premiere of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring in 1924 and he always said that made him want to be a composer. He interacted with European composers and legacies; he went to Paris for his apprenticeship. (Partch serves as a contrast here, as he backflipped over two thousand years of European tradition and went back to its origins in ancient Greece for his grounding in music and theater.) Modernism was a more severe and less playful enterprise in Europe than in America, probably because there was still so much tradition to learn and to destroy, and Carter has received a lot more popularity and support in Europe than America.

Cage’s remark, “Carter’s ideas about rhythmic modulation [we’ll get to this] are not experimental. They just extend sophistication out from tonality ideas towards ideas about modulation from one tempo to another. They put a new wing on the academy and open no doors the world outside the school” helps define what modernism is. Carter’s practices were new to the point of being alien; they were also rooted in hundreds of years of composing tradition and his great skill in applying it. Cage also pointed out an insularity to modernism, a strain in it that proclaimed its alienation from the rest of the world as a virtue, which I often call fuck-you modernism. (Don’t get this painting? Fuck you, appreciate me. Don’t enjoy this music? Fuck you, appreciate me. Carter’s contemporary Milton Babbitt wasn’t far off from this attitude with his article “The Composer as Specialist,” retitled by some jackass at High Fidelity “Who Cares If You Listen?” in the 1958 equivalent of a hot take.) Carter was too well-bred (and apparently too nice a guy) to ever phrase it that way, but it aligns with his sense of professionalism. In his career, Carter wanted a larger audience for modern classical music; for him, that meant the audience had to come to the music (through more widespread musical education), not the other way around. Unsurprisingly, as the audience for classical music (especially modern classical music) has shrunk, it’s Cage who has become far better known than Carter. Cage has a legacy in contemporary music, especially ambient, electronica, and noise; Carter does not.

The modernists were innovators; in fact, they usually get historical points equal to their number of innovations. Carter’s best-known innovation was “metric modulation,” although “tempo modulation” would be the more accurate term. Carter began developing this practice in the late 1940s; it first appears in his Cello Sonata of 1950 and gets fully realized in the First String Quartet of 1951. Carter does exactly what Cage said he did: he took a traditional, even defining practice of Western music–key modulation–and worked out a way to change between tempos with the same kind of flexibility. What this means is that Carter’s music doesn’t stay in one tempo for an entire movement, but shifts between them frequently and elegantly, and also layers different rhythms and speeds against each other. With Cage, time became an element like space, a way of “keeping everything from happening all at once.” (This is a physicist’s description of time.) Cage’s random procedures meant that sounds were arranged and separated in time as, say, the images of Robert Rauschenberg or the objects of Joseph Cornell were arranged in space. For most composers, certainly most earlier composers, time was something chosen off-the-shelf, something that became a compositional given. With Carter, time–or, more broadly, rhythm–became a plastic element, something he could shape to his own ends.

Another Carter innovation was how he divided up musical ensembles, ordering them into groups by pitch or by sound. This was something that began with his Double Concerto for Piano and Harpsichord (1961), where each solo instrument gets its own mini-orchestra, and continued until the end of his life. There are so many versions of this idea: the “concertino” for the piano (separate from the rest of the orchestra) in the Piano Concerto (1965); the Concerto for Orchestra (1969), where the orchestra gets broken into four groups; A Symphony of Three Orchestras (1976), which is almost accurate (it’s A Symphony of Three One-Third Orchestras, to be precise); Penthode (1985), for five groups of four instruments; Triple Duo (1983), which is exactly that. Having split up performers this way, Carter generates a lot of interest in how they interact. The interest comes from the range of interactions; he goes way past the traditional cooperation-or-competition style of the classical concerto. In the Piano Concerto, for example, the concertino serves as “mediator” between the piano and orchestra; in Penthode, the five groups play out a single shared melody for the entire piece.

The divided ensembles point toward another Carter technique, perhaps his most powerful: the way he wrote for each sub-ensemble–or in his chamber works, each instrument–its own “character” (his word, used a lot). Carter often gave every instrument or group a specific intervals, rhythms, and styles for playing, and then built the music out of the interactions between them. (Here, he’s the direct opposite of J. S. Bach, who wrote music that could be adapted to any instruments; one more way in which Carter took a tradition to its end.) It’s there right at the beginning of his mature career, in the Cello Sonata, with the piano ticking steadily against the rhapsodic, unevenly flowing cello:

Audio Playerand he would continue to pursue this. If the Cello Sonata was the breakthrough, the First String Quartet (1951) was the watershed, a work of classical music’s past and Carter’s future. If you took any single instrument’s passage from this and isolated it, you wouldn’t hear anything that would be out place in, say, Johannes Brahms; the innovation came from how Carter layered speeds and styles and shifted between them. Long arcs of melody get played against almost jazzy rhythms; the musicians change speeds like a race driver downshifting; the Adagio movement has sound sliding into and out of nothing like Brian Eno’s Music for Airports; trills turn into mosaics of nearly pure sound (the score uses one of Carter’s favorite tempo markings: scorrevole, scurrying)

Audio PlayerThis quartet has a Romantic breadth to it, and it’s the longest piece Carter would write (approximately 45 minutes) until the Symphonia of 1996. (Schönberg’s First String Quartet has the same quality.) After this, Carter compressed his expressions, abandoned any kind of literal repetition, and made his music even more complex. The First Quartet feels like the end of an apprenticeship, saying goodbye to old ideas and starting on the course of the rest of his creative life; when she saw the score, Boulanger said “Carter, I never thought you would write anything like this!”

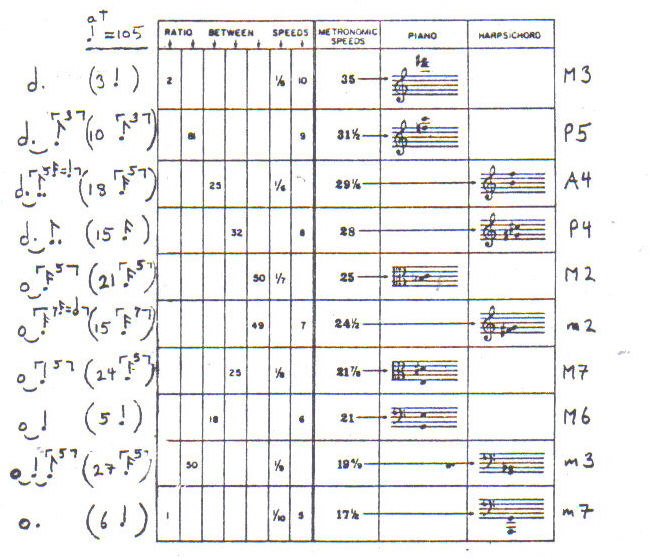

Moving into his new world of music required an incredible amount of work and skill (and paper–a single piece could use a thousand pages of sketches). Moving past two or four instruments, in the Double Concerto, each solo instrument (piano and harpsichord) gets a set of intervals to play and speeds at which to play them. Also, each of the non-solo instruments gets assigned one of those speed/interval combinations (this is not shown in the chart):

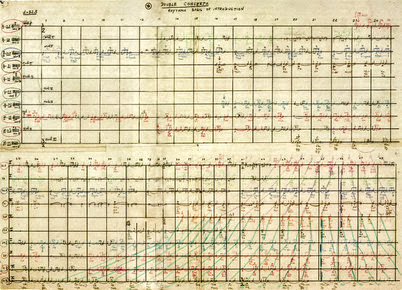

In the first movement, the intervals, speeds, and instruments all enter one by one until there’s a near-unifying point at measures 45/46. Here’s the chart (different colors indicate different instruments or groups), and I apologize that I couldn’t find or scan a better image–the way all the lines of music almost align should be clear, though:

In the first movement, the intervals, speeds, and instruments all enter one by one until there’s a near-unifying point at measures 45/46. Here’s the chart (different colors indicate different instruments or groups), and I apologize that I couldn’t find or scan a better image–the way all the lines of music almost align should be clear, though:

This is not difficulty for difficulty’s sake, all Carter’s hard work has a goal: make the sound clear to the listener. Assigning different intervals and rhythms to the instruments keeps their sonic presences distinct in the mix, in a way that (for example) the players in Ornette Coleman’s early free jazz works are not. (Later, Coleman developed a more theoretical approach to free jazz, actually a bit like Carter’s, and late music has a lot more clarity.) The expert theory is in service of making the music clear to the listener; this distinguishes him from more academic composers like Milton Babbitt, who wanted his music to be understood on the level he wrote it. Carter’s music doesn’t require a grounding in theory to get its sheer ownage; if you can follow an American football game, with almost thirty people divided into at least three groups doing different things that are still coordinated into an overall whole, you can get Carter

Carter took as the model for this opening Lucretius’ discussion in De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things) of the atomic structure of the universe, atoms colliding and accreting. Like some other modernists– Iannis Xenakis, Stravinsky, and Schönberg come to mind–Carter didn’t start his career in music. He studied literature and philosophy in college, and although he insisted on strict musical justifications for everything he did (as opposed to the “tone poems” of, say, Richard Strauss, which Carter called “imposing on [music] programs derived from non-musical experience and non-musical thought,”) literature often serves as inspiration or explanation for his works. Until the end of his career, Carter didn’t model his music after literature; rather he incorporated a literary sense into musical composition.

The literary sense begins with that idea of the instruments as characters, and it continues with the feeling of so much Carter music that we’re hearing a conversation. Sometimes he’s quite explicit about this; the Fifth String Quartet (1995) has a series of interludes that Carter treats as rehearsals of the next movement, or discussions of the previous. More pervasive, though: Carter’s approach to rhythm gives his musical lines the quality of talking rather than singing. The lines only rarely have the flowing quality we associate with singing (and if they do, there’s often a literary reason for it, where the music is alluding to something. This happens in the 1981 song cycle In Sleep, in Thunder); more often they stammer, mumble, yell, chatter, rant, explain. Carter discovered a world of sound that was always with us, but never rendered into music before, in the same way that Joyce’s Ulysses has been described as raising the everyday into literature.

Film and literature point out directions for how to listen to Carter. His music has a strong narrative drive; he wrote about the tension of listening, how music sets up expectations for what will come next, and how composers can manipulate that. Carter controls the density and variety of his sounds much more than Gyorgy Ligeti or Penderecki (or especially Cage) do; he always insisted on choosing the one right sequence of sounds above all others. (I suspect this is why he so often composed for chamber ensembles; he needed to limit the number of choices he made by limiting the number of instruments.) There’s continual transformation in a Carter piece, but no real shocks. When there’s no way to tell what comes next in any narrative, that gets boring right quick–we’re left in a state of not caring about anything. Like a good director, Carter holds our attention of perceiving.

On the larger scales, Carter’s pieces work like literature through an accumulation of references and details, often quite subtle ones: the chords that keep recurring at the end of Night Fantasies (1980) or the beginning of Symphonia; the gradual weakening of attacks in the Fourth String Quartet (1986). (As much as I’ve enjoyed performances of Carter, there’s no way I could have gotten into him without recordings and repeated listenings. This music does not give up its secrets easily.) Carter’s technique creates multiple narratives happening at once, and the interest comes from how our own minds make the connections. In this way, more than most composers, Carter’s music seems to keep changing as it’s revisited and relistened. (The other candidate for “last modernist” status, Jasper Johns–still active as of this writing–has a similarly literary approach with his paintings, considered over the course of his career. He works with allusions and quotes from his entire body of work, so seeing a new Johns painting picks up meaning from all that came before.)

Carter doesn’t give you any tunes to work with in the same way that modern paintings don’t give you any figures. Modernism had a characteristic drive to go back to the essentials of its arts, away from what was represented and towards the substance of the art itself. Writers became more concerned with the shape, sound, and placement of words; painters became more concerned with brushstrokes, color, and materials. One of the most powerful and necessary effects of this was to break our habits of viewing and seeing. Our minds actually don’t perceive all that often; mostly we remember. A clear figure in art or a clear melody in music triggers our memories: show me a painting of a cow, I see a cow, not the painting; give me an easy melody and I’ll sing it myself, I won’t hear the music. Denying these things forces our brain into paying attention to what’s there, not what we imagine is there.

In music, that modernist impulse manifested as a greater concern with sound itself. Carter never expanded his interest into electronic music, new instruments, or alternate scales (asked why not, he wonderfully said “I find the twelve notes we have keep me busy enough”); rather, he stuck with the older materials of music–the same scale, the same instruments, the same notation–but he thought about and worked with more fundamental questions than earlier composers and made us pay attention to them.

Something Carter both wrote about and composed with was the problem of the attack of a sound: how the sound appears out of silence or a background. Carter’s manages this with an appreciation for the psychology of hearing, carefully moving our attention between different lines in a composition. He also composes with an awareness of total amount of sound, both in terms of volume and density; note that these concerns go directly to basic questions of hearing. They are things that we listen to in all music, not a specialized thing we have to interpret. Both of these concerns get attention in the Double Concerto; where the opening movement accumulated the different instruments atomically into a large sound mass, the closing Coda takes as its sound-model the dying-away of the crash of a large gong, expressed through all the instruments in diminishing echoes of an initial attack:

Audio PlayerOne of the ways in which you can hear how much Carter breaks from the past: his works never end with any kind of harmonic resolution, but always with the disappearance of the sound, extensively prepared, quietly finishing. He said “in my music, it is always the still small voice that wins out.” That still small voice gets a lot of its power from everything that came before–the single quiet voice serving as exit for all the preceding complexity. Carter uses harmony as structure rather than as function: as a way to separate the instruments by giving them different intervals, using a single chord to generate the intervals, and/or by using chords as markers during the piece. He was never a twelve-tone composer (in the way another great modernist, Anton Webern, was) but a post-harmonic composer, one who avoided the entire convention of harmonic preparation and resolution.

Without harmony, he had to find structure someplace else. Interestingly, Carter often used cinematic models for the form of his music moving through time. Dude was a film fan all his life, with favorites ranging from Sergei Eisenstein to Susan Seidelman, and took some direct inspirations from movies. The entire action of The Blood of a Poet taking place in the moment a chimney collapses inspired the structure of his First String Quartet: Carter has no breaks between the formal movements here, but inserts two pauses in the middle of the movements, and the final line in the cello comes back to the opening line. Over 45 years later, Jacques Tati’s Trafic inspired his first opera, What Next? (1998)

Technically, most Carter pieces are a single movement; there are individual scenes but they overlay each other like a superimposition, or start before the other finishes like Scorsese often does. Carter’s most brilliant and (as Jason Mantzoukas sez) next-level bonkers example of cinematic layering and structure was the Third String Quartet (1971), where the instruments get broken in two duos which then play different movements (six for one duo, four for the other) in every possible combination and occasionally alone (24 combinations plus eight solos) and in which each duo and instrument has its own style of playing. It seems impossible that there are only four instruments playing here.

Audio PlayerCarter never took his skill in counterpoint as far as he did here, keeping every instrument’s sound completely clear and distinct; no expression gets lost. (Another point where Cage connects with Carter: both of them had compositions that pushed performers way past their limits of technique.) The compositions of Xenakis, Penderecki, or Ligeti have more instruments playing different things, but those composers deliberately blend them into a total sound. With Carter, the result is the most active music I’ve ever heard, a busybusybusy living mass that never settles down. If Stan Brakhage’s films aspire to condition of music, Carter here aspires to Brakhage’s densest works, especially the later ones with superimpositions of so many different levels and kinds of imagery. (I have not seen a performance or heard a recording of the Third Quartet that begins with the first violinist screaming KICK OUT THE JAMS, MOTHERFUCKER. This disappoints me.)

Where other composers (Pierre Boulez and Milton Babbitt are examples) treated their methods (total serialization, set theory) as ends in themselves, all of Carter’s techniques were exactly that: means to ends, not the reason for composing. Modern classical music became more and more academicized in the back half of the 20th century but as Carter developed his techniques through the 1950s and 1960s, his music gained an expressiveness and energy that was unique. Carter worked steadily in this period, producing only a few pieces every decade, but each one had an impact. Carter imposed the fuck-you aspect of modernism on himself, demanding that each piece be about something new. (This is also true within the music: there is almost never literal repetition in a Carter piece.) His works of the 1970s are the culmination of this development, for my money his best: the Third String Quartet, A Symphony of Three Orchestras, the Duo for Violin and Piano (1974), the solo Night Fantasies for piano. You can hear in these works practices that started out as intellectual experiments but have become so internalized to him that it’s a voice, a language really, that belongs to him alone. Metric modulation and instrumental characterization have led to melody lines that are unsingable and unforgettable, like the opening “rugged recitative” of the violin in the Duo:

Audio Playeror the trumpet solo that launches A Symphony of Three Orchestras:

Audio Playerevoking the lines from Hart Crane’s “To Brooklyn Bridge”: How many dawns, chill from his rippling rest/The seagull’s wings shall dip and pivot him. The Symphony goes from there into one of Carter’s densest and most enjoyable works. It’s the New York symphony that so many composers wanted to write: rough, argumentative (the three orchestras do a lot of yelling at each other), moody, ninety minutes of music crammed into fifteen, using the same kind of overlapping-movement structure as in the Third Quartet. (Carter imposed an interesting condition on himself: after Aaron Copland told him that so many of his “works seemed to progress with an upward inflection and so frequently ended in an upward direction,” he committed to writing the Symphony with “constant downward movement, both in the large form and many of the small details.”) It even has something I’ve never heard in any of his music after the First Quartet: some straight-up repetition, a goofy broken-rhythm figure near the end that everyone plays. It has a literary source: “I wanted to give the impression of the cessation of the poetic impulse and then the awful realization of his [Crane’s] own self-destruction from which he could not recover. My idea of awful is, you might say, when everyone plays together. I guess I’m just joking with that last remark.” Too bad, pal, I like it.

Carter’s music changed somewhat in the 1980s, with the Fourth String Quartet announcing the shift. I can’t really call it more accessible but it was certainly less dense and with a more theatrical approach, cleaner in its narratives, less interconnected in its mosaics. Carter said he became more interested in cooperation among the instrumental characters rather than competition in the Fourth Quartet. It doesn’t get back to the expansiveness of the First Quartet, but it’s pointing that way, especially after the hypercompressed music of the 1970s; the four instruments almost but not quite harmonize here. If the First Quartet was Mahlerian, this one shows Carter getting his Beethoven on, big and complex and yet somehow plainspoken:

Audio PlayerCarter’s textures thinned and he began working at both longer and shorter timescales. The longer pieces were the most interesting: the ASKO Concerto (2000), the Fifth String Quartet (1995), his third and final symphony Symphonia; his only opera, the one-act What Next? Only this last one isn’t fully successful. It sounds like a perfect subject for him: six confused characters wandering around after a car crash. He (and librettist Paul Griffiths) wrote it with a lot of cross-references and puns between the characters but it never really takes off; it feels like he’s aiming for the energy and density of his earlier work (he’s trying to do what he did in Syringa (1978); skip down to the Primer for a discussion of that one) and never gets there. It’s still a unique thing in his (and everyone else’s) music.

The other compositions are more interesting, even great. The ASKO Concerto (written for the Dutch ensemble of the same name) has a zingy energy to it; the Fifth String Quartet is one of Carter’s sparsest works, the one where more than any other, Carter used silence as an integral means of the composition, as a way of generating tension among fewer sounds. In the early 00s, I saw the Pacifica Quartet perform all five Carter quartets, and the Fifth feels like breathing out after all the incredible density and energy of the first four. It’s delicate in a way no other Carter work has been.

Symphonia: sum fluxæ pretium spei is Carter’s late-period masterpiece. (He based it on Richard Crashaw’s 17th century Latin poem, “Bulla” (Bubble)–yes, it’s about a bubble, over 300 years before Adventure Time’s “BMO Lost”; the subtitle translates as “I am the prize of flowing hope.”) The three-movement structure (with actual pauses between the movements) is conventional, but nothing else is, not even by Carter’s standards. The first movement has the energy, joy, even goofiness of his 1970s work; the second movement, though, is glacial, brooding, built on held chords in different instrumental combinations. Not a march (Carter tricks up the rhythms too much for that), not ambient drones (he keeps slipping in crescendos), it’s static and exhausted. So much of Carter’s music has been about the energy of individual lines; this is about the weight of an entire orchestra. All his previous large-scale works from the Double Concerto onwards have really been chamber pieces on a large scale, where every instrument counts; this is genuinely orchestral writing, based on the impact of the whole thing.

Audio PlayerHe may have been joking about A Symphony of Three Orchestras that his idea of awful was everyone playing together but he’s not joking here. He saves that for the final movement, as light and airy and (you knew this was coming) bubbly as the middle movement was brooding, with squiggles from the high winds tracing all around the orchestral sounds.

It was his last great work, and his longest. Beginning in the 1980s (it’s so Carter that one phase of his career starts before the current one ends), Carter stepped up the number of his compositions, but they got shorter and shorter, and this continued until the end of his career. Dude was in his 80s and 90s and even 100s and still composing, so it’s not like he was slacking off, just going in a new direction. These pieces were often written on commission, in tribute to old friends and patrons, or song cycles that were settings of poetry (by Robert Lowell, Paul Zukofsky, John Ashbery, Ezra Pound, Wallace Stevens, and others). The song cycles were more literary than musical, settings of the poems rather than distinct musical works, and they lack the unity of his earlier works. (They’re closer to collections than cycles.) The shorter works are interesting, occasionally arresting, but they don’t have the structure and grandeur of his earlier music. Even the titles–Figment, Fragment, Shard, Retracings (solo settings and expansions of single lines from his earlier works)–acknowledge the smallness of what he’s doing here. He also revised or arranged many of his pre-1950 pieces in this period.

However, some pieces near the end of his life–Sound Fields (2007) and Wind Rose (2008)–go in a completely new direction for Carter. These are both quiet works, based on held tones with no rhythmic interest at all. Describing Sound Fields, Carter said “it would be interesting to write a piece that had no changes of color, no changes of dynamic, but that had different kinds of texture.” The music resembles that of Morton Feldman and Brian Eno, but it’s closest to the time-bracket pieces that John Cage, so antithetical to Carter in so many other ways, wrote in the last decade of his life, where the players were given a set of pitches to play and periods of time in which to play them. It’s not his best work, but you have to wonder what Carter could have done with another decade, but after making it to almost 104 years and writing so much that was so transformative, that’s just greed on my part.

Audio PlayerCarter’s music, such an exemplar of modernism, can tell us some things about it–especially what it’s not. (Carter developed as a composer by explicitly rejecting a lot of compositional practices.) The fuck-you aspect of modernism has created a lot of music that’s unlistenable, art that’s unviewable, theater and movies that are unbearable, stuff that can exist only in an academic setting, where people are literally paid to see it and write about it. (In the words of the journal Music Theory Spectrum: “How could anyone object to circumstances which have given rise to so much creative thinking on the part of theorists?” which tells you where its priorities are.) Carter could only take the time to develop his music in a professional setting, and he acted in all ways as a professional, working to develop the institutions that gave him his career. Modernism can sink into self-imposed alienation (what Kurt Vonnegut called disappearing up its own asshole) but it can also use that distance to create things that are genuinely new and exciting.

I suspect the reason Carter succeeds here where others (Babbitt, Boulez) has failed is that although Carter disregards the audience he has great respect for the listener; he ignores what people (as a group) expect about music but works with how people (as individuals) hear, perceive, and anticipate sound. Where Babbitt and Boulez mathematized music for the sake of math, Carter always focused on the same elements of music that all composers have to: how it’s perceived, how to move the composition through time. (It is completely unnecessary to read the score to enjoy Carter.) In modernism’s tension between tradition and innovation, Carter was a lot more traditional than most would realize.

Modernism, as the inheritor and end point of the Enlightenment, is a humanistic movement. Going through all of Carter’s music, I can’t find anything that aims at the divine–lots of texts but no religious ones, none of the signifiers of the Western liturgical tradition. (There don’t seem to be any pieces that use the organ, either.) Contrast him with his contemporaries and near-contemporaries and you can see the difference: nothing like the unfinished Universe of Alexsandyr Scriabin, nothing like the hymns of Ives, none of the gods and monsters of Xenakis (whose music goes well past humanism into a terrifying noise). Modernism prized the individual among all other figures, the unique, distinctive, human voice. Carter’s music was all about that; he gave us dozens of different characters in his music rather than any kind of unifying, transcendent vision. Among painters, again, he’s closer to the literary, symbolic Jasper Johns than Jackson Pollock, Philip Guston, or Mark Rothko, all of whom pursued divine ideas through their abstractions. (Bruno Latour called this modernity’s conflict between immanence and transcendence, between what is right here and what is otherworldly. This comes from his book We Have Never Been Modern, and he argues that it’s a false conflict.)

On a musical level, Carter’s intense focus on the individual manifests as a concern with the horizontal aspect of music over the vertical–what would be called melody over harmony if his music didn’t straight blow both terms the fuck up. In writing his music, Carter has a great, patient concern with how all the notes sound together (the vertical aspect) but always to the same purpose for the listener: to keep all the horizontal lines clear. That’s what gives his music its unique complexity, much more complex than music (like Ives) that has more notes. Carter took, as a kind of ethical necessity, a principle of democracy: every voice needs to be heard. His music is what that sounds like, and another way in which modernism is deeply humanistic.

Olivier Messiaen serves as the strongest contemporary contrast to Carter. Born the same year (but dying 20 years earlier), he could write music that was just as mathematical and just as complex as Carter, as you can hear in the “Great Concert of Birds” from his opera Saint Francis of Assisi:

Audio PlayerWhere Carter was all about the horizontal line, Messiaen wrote and slammed down big vertical chords over and over again; where Carter was a New Yorker start to finish, Messiaen’s defining musical experience was sixty-one years as the organist for the Church of Sainte-Trinité in Paris. (No one else held that post even half as long in the history of the church.) That gave him his instinct for the vertical and for big, bold chords; some of his pieces came out of improvising on the organ during services. Carter was a rationalist, justifying every step of a composition, examining the smallest details like a biologist with an electron microscope; Messiaen was a synaesthestic (he’d get nauseous if a performer wore the wrong colors) and a mystic, with an array of beliefs, colors, and symbols written into his music. Where Carter’s music was all about the individual, Messiaen’s was forever about the glory of God, whether he pursued this in purely instrumental forms (the apocalyptic vision of Quartet for the End of Time, the loud and rigorous piano suite Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant Jesus), choral or vocal works (although it’s more of an oratorio than an opera, Saint Francis is the best example of this, it’s as committed and powerful a work as The Last Temptation of Christ), or in symphonic forms (From the Canyons to the Stars, inspired by Messiaen’s visit to Cedar Breaks–Zion National Park–Bryce Canyon in Utah). Messiaen was less a modernist than a medieval Christian with the resources of the 20th century at his command; his sound is as big and glorious as Carter’s is tight and focused.

Modernism moved art away from the divine, even away from beauty, and towards the lives of human beings. What’s so striking, even touching, about this is that you can hear the journey of Carter’s entire career in any one of his pieces: starting with something complex but conventional, and then self-organizing into a complexity that no one had ever heard before, and then falling apart into simultaneous scattered short sounds. The journey from the Cello Sonata to Sound Fields is a lifelong sounding-together, the etymology of symphony; in John Zorn’s words, “at the highest level, there is no distinction between art and life, just as form and content are the same.” Carter’s music got to that level; it turned into a single life in all its singular, multilayered, knotty glory. That alone justifies the project of modernism.

An Elliott Carter Primer

Introduction: Cello Sonata/Duo for Violin and Piano

Listening to these two together shows where Carter started, and how far he came 26 years later. The Sonata is daring and engrossing, but it’s still very much of its time and its world. (A lot of Carter’s contemporaries could have written it; Paul Hindemith would have gotten close to this. His Sonatas for Viola and Piano are just as good.) The Duo is all Carter’s own, though. (Carter was careful in choosing his titles. “Sonata” implies an entirely musical structure, and a unified one; “Duo” can be any pairing of two things, and the violin and piano are much more opposed to each other in this.)

Carter’s sense of character in his instruments begins with the Sonata and is so strong in the Duo. Listening to the whole thing, the piano comes off as older, more experienced, and therefore quieter than the violin, which is all outburst and restatements. So many of Carter’s works can be heard as conversations; I hear the Duo as the Old Pro of the piano giving advice (and occasionally just quietly, bemusedly listening) to the smart, rambling violin. Eventually the violin listens, and maybe even learns something.

Intermediate: The String Quartets

The quartets are the spine of Carter’s work–he tried or consolidated new methods in each one. As a whole, what’s most striking is the continual innovation, with each work building on some elements of the previous one and rejecting others. I’d rank the odd-numbered ones (the balls-to-the-wall Third, the expansive First, and the delicate Fifth) as my favorites, but the Fourth and the Second come only slightly behind.

Expanding the frame a bit: as a kind of Gateway to Geekery for modernist music, listening to Schönberg’s four string quartets (1905, 1908, 1927, 1936) followed by Carter’s five (1951, 1959, 1971, 1986, 1995) creates a comprehensive survey of 20th-century classical music in just under five hours, from its beginnings in the long-form ambiguities of Romanticism into the hard-edged badassitude of modernism. It’s an exhausting, endlessly fascinating, and utterly enjoyable experience.

Advanced: A Symphony of Three Orchestras

In addition to its Third Quartet-like shifting densities, this is one of Carter’s clearest triumphs of humanism over older ideals of beauty. This isn’t lyrical, it isn’t dramatic, it’s argumentative and cranky, jagged, and in the end its power comes from as much for what it lacks as for what it has. As much as Allan Pettersson’s Sixth Symphony, this is about identification with the small, and Carter loves that as it is. What is arguably John Cage’s masterwork, Apartment House 1776, came out in the same year as this and the two match up remarkably well, respectively focused and sprawling visions of America in its bicentennial year.

Syringa

Carter’s songs don’t really land for me because sticking to a single line of text and accompaniment doesn’t give him the room to do what he’s best at: layering different lines, speeds, and expressions; coming up with different instrumental combinations and characters. Syringa, though, is his most ambitious and best vocal work: a setting of John Ashbery’s poem of the same title, a meditation on the life and legend of Orpheus. (It has some of my favorite closing lines in poetry.) In Carter’s piece, a soprano sings Ashbery’s text, a guitar plays the character of Orpheus, and a baritone sings fragments of ancient Greek aphorisms and poetry, a background of legend and memory. (Another example of his skill and commitment: he includes with the score a guide to ancient Greek pronunciation.) Carter, who wrote so many instrumental lines that felt like speech, comes up with some genuinely singing vocal lines, and the twenty minutes of music here have the shifting shape (let’s stay with Greek legend and call it Protean) and narrative drive of his best music, but there’s a clarity here too that anticipates the post-Fourth Quartet music. Like Joyce’s Ulysses in its referentiality, like Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde in its impact, this is a work that’s equally musical and literary, complex and transparent at the same time, and moving as all hell.

Night Fantasies

Carter said he had written fifty different kinds of piano music before he started work on Night Fantasies, and where most composers would, y’know, write fifty different pieces from that, Carter threw them all into a single composition. He has described this piece as evoking the way the mind jumps around during an insomniac night, and he gets that right in the way the music seems always about to stabilize and never does. Chords and phrases and passages, some of them quite beautiful, some of them startling (ain’t no keyboard run like a Carter keyboard run ‘cuz a Carter run has thematic unity) loom up and fall away; they almost come back and you’re left wondering “have I heard that before?” The overall structure of the pieces comes from two tempos that converge near the end; a big chord starts showing up there and repeats just long enough to make us expect an ending, which doesn’t happen. Carter pulls off something almost impossible here: manipulating and denying our expectations without ever becoming boring. Play it quietly, and late.