- “It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry”, The Bootleg Series, Vol 5

- “The Man In Me”, New Morning

- “She Belongs To Me”, The Bootleg Series, Vol 4

- “Someday Baby”, Modern Times

- “All I Really Want To Do”, Another Side Of Bob Dylan

- “Corrina, Corrina”, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan

- “PS I Love You”, Triplicate

- “Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here With You”, Nashville Skyline

- “Absolutely Sweet Marie”, Blonde On Blonde

- “Buckets Of Rain”, Blood On The Tracks

- “Abandoned Love”, Biograph

- “Isis”, The Bootleg Series, Vol 5

I’ve become a standard man / greeting my heart at the door. / I’ve become a standard man. / So far it’s not bad.

– CM Crockford, “Standard Man”“This is an autobiographical song.”

– Bob Dylan, “It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry”

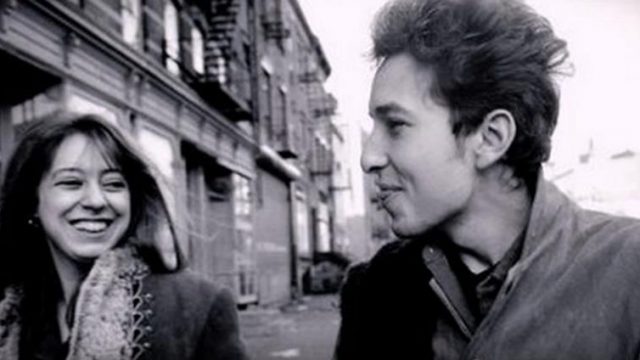

The thing that fascinates me about art is that our taste in it can be treated as Romantically as our creation of it. I actually put off listening to “Masters Of War” because when I asked Conor Crockford for a Dylan playlist, I figured it would be on there somewhere, but instead he gave me an autobiographical playlist. Right now (and he gave me permission to talk about this), Conor is around the one year anniversary with his girlfriend, and so he’s in the depths of romantic bliss, and “Queen Janes” is united not just in theme but in that particular mood. Obviously, one can take the use of art one likes as an expression of identity too far – see fandoms getting completely possessive over ‘their’ media – but one could look at the art one is drawn to as a way of either explaining yourself to others in a fast and easy way, or as a way of taking your own temperature – of identifying where you’re at using the images and sounds you keep being drawn to. With Dylan especially, you generally have either the overall emotion of a song, or one of the fragments of an image he throws at you in the lyrics (the way I was attracted to the phrase “I already confessed, no need to confess again”, from which I ended up finding meaning in all the lyrics “Thunder On The Mountain”).

(Perhaps there’s also another option, in which art expresses who we would like to be, the way Dylan defined himself with “Song For Woody”.)

What’s especially exciting for me is the new way of arranging Dylan this presents. His albums show him getting into a groove, where he’s generally caught up in the one mood and rearranging the same few ideas and tools until his feels his mood is sufficiently expressed. Choosing his songs randomly means jumping hysterically from one mood and set of tools to another. Choosing his songs by theme was fun, showing the many ways he could feel about the one concept (and it worked really well with his religious beliefs, where his feelings changed radically over time). This is the reverse, as he finds many different ways of expressing the one feeling, which sometimes translates to finding totally different points in the one otherwise happy relationship – or, at the very least, the way the same feeling can have different variations over the course of a single person’s life. It says something that I never felt myself bored or trapped by the seemingly limited scope of interest the way I can with really early Beatles albums (though this is also a reflection of Conor’s ability to lay out a playlist). Something I sometimes think about is the way this project demonstrates how an album of original music could be generated and arranged – someone looking at how they could use the same few tools to generate wildly different emotions, which as far as I can tell is not something Dylan really goes in for.

I’m sure there’s a way to open an album with a quiet acoustic or semi-acoustic number, but God help me, I can’t resist the siren call of a blistering rock number like “It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry”. One of the fundamental truths the Solute has bashed out in our discussions is that one must put the biggest piece of spectacle as close to the front of a story as possible and then track how its consequences play out, as opposed to ending with big mushy setpieces. I don’t know how well that tracks with things like music, but there’s definitely something in how the relentless energy of this piece grabs me by the ear and carries me through the next few songs. Ever since my article on Dylan’s religious music, I’ve made the effort to look up information on each individual song, which was very useful here because I couldn’t parse the meaning of the lyrics and somehow completely missed the idea that it’s about sexual frustration. Even afterwards, lyrics-wise I still don’t see it (is the train a penis?), but it definitely, totally fits the music. That pounding music that’s heading in directly and uncompromisingly towards its screaming climax, only to find the relief is temporary and the process is starting all over again, certainly sounds like sexual frustration. If this captures a specific part of a relationship, it’s the very, very beginning, when all you have is an image to drive your initial interest.

I was going nuts trying to figure out where I’d heard “The Man In Me” before, and discovering it was used in The Big Lebowski was a head-slap moment. It captures the moment in a relationship when you’re revealing the layers of yourself you generally hide from most people – the raw emotions and thoughts that you hold onto because it would hurt to be rejected over them. Dylan feels relief at letting the man in him out, and he thanks the woman he fell in love with for letting him out. You know, I’ve read that men tend to take break-ups worse than women because women traditionally create many outlets for their personal feelings whereas men traditionally exclusively use their partners for that, and losing that tends to be a massive blow to their self-esteem, which casts a pretty dark pall over the song. Nevertheless, the moment when you’re free to be yourself is always a relief. “She Belongs To Me” is more observational, Dylan pulling back to look at all the details of the one he loves. Wikipedia has what I can only assume is a fight between multiple contributors over who exactly he’s referring to and what exactly he means by phrases like “walking antique”, which I don’t think is quite the right way to approach it. Dylan’s acoustic performances on the “Royal Albert Hall” concert are ethereal, reflective, and peaceful, like he’s performing from another world only accessible by crawling through a hole in a tree stump. He’s sitting in a corner watching the world go by, and the point to me is less what he specifically notices and more that she’s worth noticing at all.

My read of “Someday Baby” is heavily influenced by my perception of Dylan. My take is that he had reached a sense of peace right around Modern Times, where he had become comfortable with the distance between himself, the world, and God, no longer railing against a world gone wrong. The song stands out against the rest on this playlist in that it’s not blissful at all, but rather on edge. So I end up thinking of it as like a Zen master who’s got bills to pay – not only does inner peace not translate to a peaceful life, it’s supposed to act as a centre of gravity for when things go terribly wrong, like the romantic troubles that have befallen Dylan here. “All I Really Want To Do” is especially endearing to me because I can totally get behind both the aesthetic and thematic conceits of the song – I love the idea that to Dylan, one does not control the object of one’s love, but simply exists in their presence, and that’s definitely the kind of relationship (romantic or otherwise) that I’m attracted to. I also love how casual the performance is, filled with laughter and sniffing and playful riffs on the melody, and I love whenever Dylan makes an entire song about the one thing. I generally accept that his songs will wander all over the place in terms of topic, but I love things like this or “Times They Are A-Changin'” or “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” where he suddenly takes up a tight discipline and delivers ninety variations on the one idea.

(I’m also amused by the fact that much of what he describes is stuff I do, like analysing, categorising, and defining. I get the vibe from his whole career that Bob Dylan would find me really annoying, which tickles me for some reason.)

“Corrina, Corrina” is another reflective acoustic song, but this time he’s singing about a woman who’s very far away. It sits in a rather confusing spot between being a cover and being one of his lyrical/musical mashups, lifting the structure from the Mississippi Sheiks version of “Corrine, Corrina” and the melody and a few phrases from Robert Johnson’s “Stones In My Passway”. I checked both versions out and I’m shocked at how different all three songs actually sound. Johnson and Bo Carter are playful in completely different ways, playing to a crowd; Dylan is too steady to be depressed but is clearly unhappy and wistful. Dylan’s version makes me think of the one time I ever saw my parents separated for any length of time, when my mother had to go back home while my dad lived with me in the city as I looked for work and a place to live. Dylan’s voice on “Corrina, Corrina” sounds just like my dad was when he was on the phone with her; there’s a clear empty space where a person ought to be. I know I wrote a whole article on the idea of creativity coming from mashing ideas up, but it surprises me to see it work so well in action. I wonder how much the idea of plagiarism is actually preventing the creation of great art. Certainly, young artists ought to be flatly encouraged to plagiarise their early works – to use other works as training wheels.

It’s amazing how much more I enjoy Great American Songbook-era Dylan now that I’ve properly processed him. “PS, I Love You” (not to be confused with the Beatles song of the same name and overall premise) is a version of Dylan that has found his love, and the monotony of one day to another has become delightfully comfortable. It’s charming to me that whereas his live performances completely destroy every melody that comes out of his mouth, his recorded performances are downright conventional, with him comfortably leaving massive Sinatra-esque gaps between lyrics that makes them feel more certain. Francis Ford Coppola observed that when you’re eighty, you don’t have to talk about anything you don’t want to, and Dylan in these performances reminds me of my grandfather, who never seems to stutter. I admit to admiring that because I can never quite get my writing as efficient or straightforward as I’d like it to be. This is love as an old man feels it, that pleasure in someone’s presence at its most effortless.

“Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here With You”, I must shamefully admit, got a big unintentional laugh out of me. It wasn’t just that Dylan’s voice was comically out of step with his usual singing, it was that it sounded like a parody of Paul McCartney. Once I got past that, though, I found myself charmed; his country music always seems the most undigested to me, never quite transforming it from a decent genre song to a Bob Dylan song, and that’s perfectly fine here. I think its the sweetness infused with wisdom that really gets me, as the melody is sentimental and there are a few little tricks like the kick into the final chorus that back up thoughtful lyrics. This is a song about the decision to stay with someone; the central image of throwing his ticket out the window is so perfect as a way of conveying the finality of that. “Absolutely Sweet Marie” is another anxiety-ridden love song, without the Zen certainty of “Someday Baby”. Before I checked the lyrics, I thought it was like “Visions Of Johanna” or “I Want You” (also from Blonde In Blonde) in that romantic attraction to someone was a small part of a song that was absolutely and deliberately stuffed with too much, providing an inner balance. Closer inspection reveals that every line is about Sweet Marie and the narrator’s confusion and hurt over her. Perhaps I’m listening to this out of order, and it’s the point before “Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here With You” and before “All I Really Want To Do”, when the narrator hasn’t made up his mind about her.

(It’s also another case of me absorbing a lyric and bouncing it around my head. “To live outside the law, you must be honest” is a line wallflower referenced in his Shield essays, but hearing it come out of Dylan’s mouth in the context of an actual song made me think it over. It’s the kind of paradox Oscar Wilde loved, and not only does it make sense on its own – people tend to forgive you for breaking established rules if you make it clear you’re never going to follow them, make it clear why, and stand by your reasons for doing so – it makes sense in the reverse – to live inside the law, you must be dishonest – and makes sense when you swap out the terms for other things – to live a philosophical ideal, you must study reality; to live selfishly, you must understand what others want; to be lazy, you must work hard. What does this have to do with Sweet Marie? No idea.)

“Buckets Of Rain” is clearly set a few decades after “She Belongs To Me” and a few decades before “PS I Love You”, and indeed feels like a redo of “Visions Of Johanna” or “I Want You” set some time further into the relationship. Those visions of Johanna kept the narrator stable during the tumultuous weirdness of everyday life; “Buckets Of Rain” makes the same point over a much longer period of time. I love the chord progression at the end of each verse, acceptance that’s one step short of resignation. “Abandoned Love” is interesting for all the contradictions that make up its conception; Wikipedia reliably tells me it was written during Dylan’s divorce, but it sounds so upbeat and cheerful. Conor wanted me to pick up a live version of this, but iTunes didn’t have the exact version he was thinking of, so he let me pick up the Biograph version instead; I enjoy this for being a rare moment of a Dylan country song actually muddling the genre into something stranger, with the melody having a lot of country’s bouncy melodies but never falling into the genre completely. Put a knife to my throat, and I’d say this captures the point in a breakup where the narrator realises that he’s wronged as much as he has been wronged, and that the relationship has run its course, and he’s not even hurt or angry about that anymore. But I find many lines from it bouncing around my head (I love “take off your heavy makeup and your shawl” the most, but also “my heart is telling me ‘I love you but you’re strange'” and “my patron saint is fighting with a ghost”). I feel like this is a song I’m going to warp into being about me somehow.

I love that Conor structured the playlist to begin and end with the Rolling Thunder Revue, and “Isis” is the perfect song to end on – it goes so far into that apocalyptic hoedown aesthetic that I can practically hear the facepaint. The song feels like it makes the entire career of Nirvana completely redundant, because it does the whole ‘alternating between loud and quiet sections’ more perfectly than anyone has ever done them. I hate dancing – the picture Ruck Colchez repeatedly painted in his “Ten Years Later” series of dancing in a club, drowned out by music and in sync with all the people around him, was both incredibly moving and made me realise that the reason I don’t like a lot of pop music is because it’s designed to be listened to under conditions that physically repulse me – but murdering people to music is an activity I’ve enjoyed as long as I’ve been playing violent video games, and that hysterical, earthshattering bridge conveys gleeful ownage better than anything I’ve ever heard. It sounds like a circus angrily exploding. But the so-called ‘quiet’ sections are loud even on their own, with the various instruments comically underlining Dylan’s vocals like the instruments in “I Am The Walrus”. It’s not quiet and loud, it’s intense and hysterical. In terms of the theme, it’s interesting for being what I thought “Absolutely Sweet Marie” was about, with romantic bliss being the centre of gravity – indeed, the home – of a much bigger story. The narrator marries Isis, then leaves her, then comes back, older and wiser. It’s interesting to think of our relationships as a source of home, though of course, the biographical details of Dylan’s life show how that can fall apart.