- “Highway 61 Revisited”, Highway 61 Revisited, 1965

- “God Knows”, The Bootleg Series, Vol 8

- “Gates Of Eden”, Bringing It All Back Home, 1965

- “Hark The Herald Angels Sing”, Christmas In The Heart, 2009

- “Cat’s In The Well”, Under The Red Sky, 1990

- “Long Ago, Far Away”, The Bootleg Series, Vol 9

- “Pay In Blood”, Tempest, 2012

- “When The Ship Comes In” (Live), The Bootleg Series, Vol 7

- “In The Garden” (Live In London), The Bootleg Series, Vol 13

- “Thunder On The Mountain”, Modern Times, 2006

- “Every Grain Of Sand”, The Bootleg Series, Vol 1-3

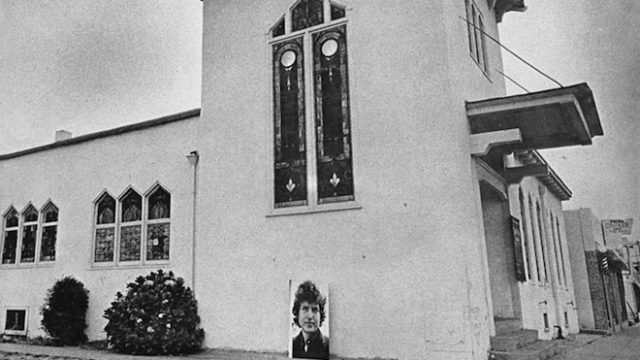

For this article, I had to do something I’ve not done here before and actually research it beyond, you know, the material at hand. After failing to find anything relevant on the internet, I even went to the effort of buying and reading one (1) book on the subject – Bob Dylan: A Spiritual Life, by Scott Marshall. It was an interesting and at points all-consuming read, a collation of everything Dylan and his friends, family, and fans have ever said on the subject of his religious beliefs, intertwined with analysis of Dylan’s songs. At this point, there are things I discovered that did not surprise me at all, like that Dylan’s shift into gospel was, despite the desperate imaginings of some of his fans, entirely sincere. One of the songs on this album actually doesn’t belong – I sometimes buy individual Dylan songs I want to listen to, and “When The Ship Comes In” was one of the songs Marshall highlighted as having a few specific Biblical allusions as opposed to being about God specifically, and I mixed it up with “Sign On The Cross” when putting the playlist together. But it’s also the only song on the album that fits what I believe is the iconic image of Bob Dylan – a man with an acoustic guitar and a harmonica, singing a patter song built out of fragments of images smashed together into a cohesive whole. It got me thinking about Bob Dylan, Icon.

It’s as if Dylan fashions himself into a different icon every few years, and people get attached to that one idea of a person, and project onto it to the point of ignoring any contradictory data that comes their way. Even without knowing in advance that Dylan went through a born-again period (wow, talking about history is the one place I’ll ever have the time traveler’s grammar trouble), even without reading up interviews where he said he always believed in God, the frequency and context with which he drops Biblical names and phrases make his spiritual convictions if not predictable then at least unsurprising. But people decided that, because he was a counter-cultural revolutionary, therefore he was an atheist. It makes me think of what beloved Soluter wallflower said way back at the start of this series, how Dylan preemptively separates the art from the artist. He gives us cool turns of phrase and we imprint our own meaning onto them. The mistake these people keep making is doing the same thing to Dylan as a human being.

In that spirit, I also learned things that genuinely shocked me. Like I said, it’s not terribly shocking to learn that Dylan always believed in God, and in fact I wonder how much of who he is and what he’s done comes from it. If there’s one consistent thing about his persona, it’s the superhuman amount of confidence he projects – not in the sense of grandiose declarations of his own importance (although sometimes a little of that) but in that he walks into a room and speaks and acts and sings without hesitation. Does he do what he does because he believes it’s what God wants from him, and that gives him conviction? He seems to treat every performance as its own unique object, changing the melody and the instruments and the tone even when he doesn’t have to. Has he been performing for God this whole time, knowing somebody out there is keeping a record of the things Dylan does, and we’ve just been lucky enough to overhear the conversation between the two this whole time? One of the possibilities of this particular essay is finding a compelling argument for renouncing my atheism and believing in God; there wasn’t any combination of words that blew my nips off, but this is a compelling practical argument for believing in God – stability.

(Oddly, the really shocking thing was discovering that Dylan doesn’t believe in moral relativism. “Gates Of Eden” ends on the most beautiful expression of his stance: “At times I think there are no words/But these to tell what’s true/And there are no truths outside the Gates of Eden”. The sense I get from Marshall’s book is that Dylan sees a single moral truth that everyone comes to from different angles (“We always did feel the same/We just saw it from a different point/Of view”) as opposed to a different truth for each person. This is how “When The Ship Comes In” manages to fit into the whole album, in that it’s about God coming for people whether they like it or not)

One of the other possibilities is finding phrases that manage to cross the divide and feel like an expression of my worldview anyway; I was caught by a lyric Marshall mentioned from “Thunder On The Mountain”, “I already confessed, don’t need to confess again”. The final possibility is understanding Bob Dylan himself, and this phrase feels like a skeleton key to the cycles of his career. When Dylan stopped releasing gospel albums, they assumed he had renounced his Christianity, but this was no more true than saying he’d renounced country music. As Marshall observes, Dylan continued to sing Jesus stuff in his live shows well after he supposedly gave up on the whole thing; if he digests ideas, to use Rosy Fingers‘ phrase, perhaps he chews with his mouth open, and when he moves on, it isn’t because he’s bored with an idea or abandoning it, it’s because he’s fully absorbed it to his satisfaction, and while some ideas slip away, others are permanently absorbed into the idea of Bob Dylan. Not necessarily allowed to come to the surface as often, but still present. Once you’ve said you’re in love with someone, or that you like country music, or that you believe in God, there’s not much point saying it a second time because you’re not saying any new information. That ties into the song as a whole, I believe; according to Marshall, Dylan’s gospel period saw him at his most humourless and preachy, and it was a few years before writing “Thunder” that saw him lighten the fuck up a bit, and I’d suggest he had slowly reconciled himself to the distance between him, God, and the rest of the world.

But the phrase worked its way into my brain for more than that. I like learning, I like growing as a person, I like feeling like I’m always moving forward. I’ve been trapped in stasis because of emotional weakness and neuroses, but I’ve also been trapped in stasis because I was surrounded by people who were actively resistant to the idea of genuine change and kept reciting the same affirmations or platitudes. A topically relevant example is atheists whose thoughts on their unspirituality begin and ends with making fun of Sky Dumbledore. I accept the premise that there is no God, but I need to follow that thought all the way; the belief that there is no divine being controlling events behind the scenes and the belief that Good and Evil are intrinsic properties to either people or actions seems totally contradictory to me, so, like, statements like “religious institutions are inherently evil because they get people to do things for something that isn’t true” is nonsensical because who said Truth was inherently preferable to Falsehood? And more relevantly to my point, most atheists strike me as completely comfortable just saying “there is no God” over and over in many permutations, never progressing. I’ve already confessed my atheism. Of what use is there in confessing again?

(Something else I had a strong emotional reaction to because of my personal journey: cackling at the line “I’ll say this, I don’t give a damn about your dreams.” I feel like “Thunder” was Dylan just relaxing again and doing what he does best, putting words together in a way that sounds cool; I listened to “In The Garden” because Dylan frequently cites it as his most underrated song and plays it in concert all the time, and was quite disappointed to find that I actually hate it. Aside from the lyrics being made entirely out of rhetorical questions, which are at least a little annoying just on general principle, the music feels like it never gets anywhere, like Dylan is straining to reach the listener.)

I will admit that I kind of had my guard up listening to this; I feel like ever since my Kill Bill essay, I’ve had my guard up in some way with the art I consume, and deliberately listening to music with a worldview stereotypically understood for being preachy ended up drawing attention to how trying to focus on and process my individual reaction to things has put a distance between me and art in a way I don’t like. This occurred to me while listening to “Thunder” on a walk, and so I resolved to lose myself in art the way I feel I used to, beginning with the music I was listening to at that exact moment. And so I found “Every Grain Of Sand” shockingly moving; Dylan was describing the experience of realising that, if God made everything, then He made everything – that every leaf, every puff of wind, every grain of sand (“hey, that’s the name of the song!”) has the love and attention that a musician puts into his songs, and that love fuels the universe in even the most minute ways. It was a strange feeling that I had never felt before and genuinely rocked my world. Time passed, the feeling faded, the general sense that the world just kind of tumbles about came back; I’ve mostly decided that what I was experiencing was empathy for Bob Dylan, but I’m still not entirely sure what it means that I’m capable of experiencing that specific emotion. I have, however, decided I respect that Bob Dylan takes his belief in God so far.

SCATTERED NOTES

- Aside from “In The Garden”, the music in this album is red hot blistering ownage. It’s as if Dylan decided to try and court me, personally, with the coolest music he could think of.

- I expected “God Knows” to be more religious than it was, but I was surprised to find that it’s more of a bunch of riffing, seeing how many sentences can begin with “God knows”. Some of it’s religious, some of it’s just a cliche people throw into their every day language.

- “Hark The Herald Angels Sing” was chosen as a reflection of something I picked up from the book – how around the 00’s Dylan was reaching back further into the past in his live concerts to pull out traditional religious songs. Dylan is as much a nerd about God as he is about American music.

- I really wanted “Long Ago, Far Away” because according to the book it’s one of the first songs Dylan ever wrote. It leaves me in awe of his staggering natural talent; there’s a strong element of his craft not yet being developed because the melody sounds like five melodies slammed together, but the beautiful language is already present. It’s also hilarious to me how his first song is literally a song about Creation.

- I complain about the many rhetorical questions of “In The Garden” but I’ve already found it useful as a tool in essay writing. I at least have the decency to try and answer them.