Even I don’t consider the Disney Studios in the Walt era to have been anything near progressive. I maintain that he wasn’t as racist as some people think—what you say is “not terribly racist for his time,” which is hardly a glowing endorsement—and about the same with sexism. And, of course, he was a big ol’ union buster. But it is also true that the studio had more ethnic diversity than Warners did in their animation division at the time; the only person from the studio mentioned in Chuck Amuck who wasn’t a white dude was the janitor. Whereas Milton Quon is one of two people who animated at Disney during the same era who was Chinese-American—and indeed, Jones and Quon were students at Chouinard Art Institute at roughly the same time.

Not that all Quon did was animate for Disney, but he’s definitely one of those “if it were all it would be enough” bits. He’s uncredited, because animators pretty well were at the time, but we know he worked on Fantasia and Dumbo. He was an in-betweener, not a key animator, but so what? You’ve still seen his work on the screen, and animation wouldn’t exist without a whole lot of in-betweeners unless you’re one of those overachievers capable of doing the whole thing alone, and there’d definitely be a lot less animation if we relied on that.

He’s one of the many animators who left Disney for government work during the war, in his case illustrating repair manuals for the Douglas Aircraft Company. This is an aspect of the war seldom discussed, but men of wildly varying educational backgrounds were required to figure out how to repair things and keep them going in extremely unhelpful environments. The illustrations done by Quon and others helped make that possible, just one of dozens of behind-the-scenes jobs needed by the military.

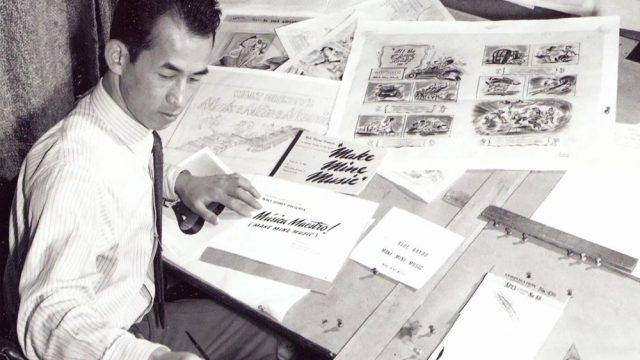

And even after that, he kept going; he returned to Disney to work in the publicity department. Make Mine Music may be a lesser-known Disney effort, one of the notorious Package Films, but Quon worked on its publicizing. And on Song of the South, just to make that film’s history even more complicated. He continued his work for five more years before moving into advertising. He was the first Chinese-American art director for a major advertising company. He then went on to design for Sealright Co., a packaging company, though I can’t find examples of his work from them right now.

After his retirement at a ripe age, it was still only the ’80s. But he kept drawing. He did a show together with his son, which must have been nicely pleasing for someone whose mother didn’t want him to be an artist. And in amazing information, he and his wife, Peggy, married in 1944. She survives him.