Sometimes the double features fall in your lap. We had just watched Air — the number one movie on Amazon Prime! — and were looking for something to follow it. And because I was visiting my mom and have poisoned her algorithm with various Cannon flicks (mostly starring Charles Bronson), Street Smart popped up. A slick 2023 crowdpleasing docudrama and a Montreal-standing-in-for-NYC 1987 crime flick wound up having a fair amount in common. Or maybe just one big thing in common — they both revolve around a story about a fiction, an 80s man who everyone wants to meet but doesn’t actually exist.

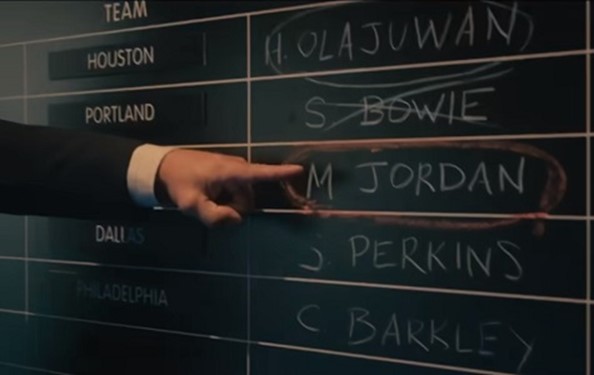

Air opens with Dire Straits’ classic “Money For Nothing” to indicate it takes place in 1984, with clips of Reagan and the “where’s the beef?” lady and various other real-world cultural signifiers to slam the point home. It’s a perfect synecdoche for the movie as ostensible recreation of a time that doesn’t bother with the darkness, cutting off before we get to the verse about the “little f*ggot with the earring and the makeup.” Wouldn’t want to sour the vibe. The movie tells the story of Nike employee Sonny Vaccaro convincing his co-workers and boss Phil Knight to invest their miniscule NBA marketing budget (the company is worth billions but is devoted to running gear, not basketball shoes) entirely on one man — the recently-graduated Michael Jordan. A top prospect, sure, but not one expected to be any more than a solid player. And Jordan is devoted to rival Adidas anyway. Even if the tracksuits sign off on the plan, it’s extremely unlikely Jordan will go along with it.

Not that we ever hear this from Jordan. His mother Deloris is the lead negotiator for all contracts and Viola Davis’ performance is “steely” and “tough” and all the other cliches you could want – it’s fine, really! And largely accurate to what actually happened, I’m sure. But it is cover for a curious omission. Jordan is played by Damian Young and gets a few murmurs of dialogue, but we never see his face or hear anything from him beyond a “hello” or two. Director Ben Affleck did that on purpose, he explained:

“… There is no way I was ever going to ask an audience to believe that anybody other than Michael Jordan was Michael Jordan. Which was also out of my own naked self interest, frankly, because I knew it would destroy the movie. You will see him [in archival clips] in the movie, but you will see Michael Jordan as he truly is in his authentic masterful genius which exists for all of us to see. It was a deliberate choice. I thought he was too majestic to have anyone impersonate him and — as I told him — ‘You’re too old to play the part.'”

Having someone else play Michael Jordan the athlete at any stage of his existence, including today, would certainly be unconvincing. But this movie’s Michael Jordan, when he does appear on screen, is sitting at boardroom tables and getting out of limos. It doesn’t seem too hard to portray that! But look at Affleck’s language describing a “majestic,” “authentic masterful genius.” A legend, even though at the time depicted that legendary status was still far in the future. The triumph the movie depicts is not Jordan’s stature as the greatest basketball player of all time but Sonny’s recognition of this potential and recognition that it could make a shit-ton of money. With the right story.

Street Smart begins with writer Jonathan Fisher trying to find the right story to pitch to his imperious magazine editor and getting shot down again and again. In desperation, he pitches a humdinger: He’ll do a deep profile of a Times Square pimp, get his takes on politics and art and society. The editor bites hard and Fisher now has to contend with the problem of not knowing any pimps, let alone ones with opinions on the big issues of 1987 (presumably the upcoming NFL strike and the integrity of Caspar Weinberger). But it’s not like New York City is short on pimps. We meet one named Fast Black, who tries to talk down a rude john slapping around a woman in his stable and winds up accidentally killing the dude* and being charged with murder.

Fisher does meet Punchy, a sex worker in Fast Black’s stable who takes pity on him and his crappy journalistic instincts (to the eventual consternation of Fisher’s yuppie girlfriend Alison). But he inadvertently ties himself to Fast Black in another way. Up against his deadline and with no actual reporting to draw from, Fisher just makes the whole profile up. And it’s a huge hit! His editor loves it and puts it on the cover and the story becomes the talk of the town, this hep, knowing, salacious and stereotype-confirming portrayal of “Tyrone,” a (of course) Black guy with properties in Malibu and colorful opinions. Fisher winds up getting his own investigative TV show, “Street Smart,” out of the whole deal. But he also gets the attention of both the DA prosecuting and the attorney defending Fast Black, who are convinced he’s actually the subject of the profile. They demand Fisher’s nonexistent notes – the DA for evidence, the defense attorney to muddy the waters with First Amendment issues – and Fast Black, knowing full well that he’s not the subject, uses Punchy to get close to Fisher and pressure him into creating notes that exonerate him. In the meantime, he plays the role of “Tyrone” for Fisher’s editor and high society friends, who are delighted to slum with such a crude fellow.

In his review at the time, Roger Ebert noted that the movie mixes two stories — one is the satirical rise of Fisher through a world of journalism that prides itself on being real and yet is contemptibly phony and patronizing and oblivious, and how Fisher fits right in with his casually racist creation that everyone is eager to believe in and his gimmick-heavy hidden camera stunt TV reporting**. The other story is much darker, following the real Fast Black trying to get out from under the murder rap and running his business of exploiting sex workers. He does this through abuse both physical and mental, with the most excruciating scene harnessing both. An earlier intimidation has Fast Black threatening to carve a woman’s face with a smashed YooHoo bottle, but after Punchy starts getting too close to Fisher for comfort, he holds a pair of scissors to her eyes and tells her to choose. Which one, left or right? This is done with a quiet, calm voice that is more frightening than his yelling and even though he ultimately puts the scissors down, he doesn’t do so until that choice is made. And that’s the point, to show that he is in complete control here. Stepping out of line is unthinkable. This is as real as it gets.

Who is playing this vicious sex slaver capable of freezing your blood with only his menacing voice? Morgan Freeman, of course. The role got him his first Oscar nomination and while he’s played villains since then it’s quite the charge to see a guy best known for The Electric Company beforehand and (grand)fatherly wisdom and kindness afterwards as such a cruel figure. There’s another meta aspect at play in the casting, as Fisher is played by Christopher Reeve*** as an almost anti-Clark Kent, where that boyish and charming face covers for a shitty reporter. (As his editor, Andre Gregory feels like he is channeling specific snooty and blithe pricks he’s dealt with in the New York literary world.) Air’s casting plays on friendlier associations — it reunites wunderkinds Affleck as Phil Knight and Matt Damon as Vaccaro and lets them bust each other’s balls 25 years after Good Will Hunting. Affleck’s comic arrogance that shades into dopiness is a way to humanize a self-processed Buddhist whose life is based around acquisition and desire, while Damon’s longstanding talent for getting audiences to pull for alleged underdogs who are actually highly skilled — geniuses of math, of violence, of sociopathy — is channeled into yet another brilliant guy no one believes in. (Meanwhile, Jason Bateman does the movie’s best work as mid-level corporate exec Rob Strasser and never pretends to be anything other than a company man, just one with Bateman’s prenatural gift for delivery.)

To be fair, Vaccaro is not an untalented guy. At the very end of the movie is an interesting note that the real Vaccaro has played a major role in lawsuits leading to college players obtaining Name/Image/Likeness rights, basically the long-denied ability for so-called “student-athletes” to make the same kind of money via endorsement that the pros do. That’s a shift with huge implications, a major triumph for thousands if not millions of people, one worth knowing about, but maybe that kind of collective action is not as good or simple a story as Jordan’s. And maybe the institutions so eager to collaborate with Air’s story, which leaves everyone besides Adidas looking good, would be less eager to lend their images and logos to a tale like that, which points out their exploitation instead of focusing on triumph.

Because to be fair again, Air emphasizes how Jordan’s contract with Nike — negotiated at Deloris’ insistence — gives him a cut of the profits instead of a one and done payoff, changing how such deals were inked going forward and sending millions if not billions of dollars to athletes as well as the companies they’re shilling for. An epochal shift with huge implications that Vaccaro can’t grasp initially, telling Deloris that it’s out of the question not because he believes she’s wrong but because he can’t believe things would change. The movie very briefly acknowledges the secret of generating wealth — paying someone nothing and getting a little is better than paying them something and getting a lot. Because a little and something and a lot are all numbers that can change, maybe to your benefit, but “zero” to the worker will always keep them from getting yours. Knight, the billionaire Buddhist, is the one who OKs the new paradigm and why not? It makes everyone involved rich. It’s a happy story of wealth generation for everyone, the kind capitalism needs to say is possible even for the people getting nothing.

And it exists because, when it was crunch time (pitch time) and the game was on the line (ad guys needed to make a sale), Sonny Vaccaro told Michael Jordan a story. He speaks for minutes on end in that Nike boardroom, so much of this movie about a basketball player takes place on ugly carpet and under fluorescent lights, telling Jordan what his life will be. And while we never see “Jordan’s” face we can now see the real man and athlete through game and news clips, proving every word Vaccaro predicts true — the accomplishments, the championships, the tragedies, the return from exile if not the exile for gambling debts itself, the global domination. It’s a phenomenal montage, the images of the man in flight still look incredible, and it of course looks just like a Nike commercial. The movie sells our past as the film’s future, a deal with a 100 percent guarantee. But that certainty is only part of the sell. “A shoe is just a shoe until somebody steps into it. Then it has meaning,” Vacarro says. “The rest of us just want a chance to touch that greatness. We need you in these shoes not so you have meaning in your life, but so that we have meaning in ours.” Product and person are merged, the people buying the shoe become real because the shoe is worn by a greater person. But the fact that we don’t see that person’s face here gives this particular game away, it’s always about the product above all. And hey, it is a successful product – in Street Smart, Fast Black crashes a playground basketball game and sure enough, some players are clad in Air Jordans.

Air is an advertisement for Air: A fun depiction of an important moment a long time ago. The movie’s soundtrack reinforces this, it’s almost entirely familiar songs from 1984 and a few years earlier, a playlist to remind you that you love the 80s****. While grudging respect must be given to Affleck for refusing the easy layup of Van Halen’s “Jump,” the Night Ranger and Violent Femmes and Run-D.M.C. tracks fall into the classic period piece dilemma of using specific cultural signifiers instead of the broader stew that we actually consume at any given moment. Street Smart has some contemporary tracks but also drops in older ones, they give the then-contemporary setting actual texture, and if Jerry Schatzberg had to shoot a big chunk of the movie in Canada at least he finds grotty streets and frou-frou parties, scummy motels and wide-open lofts, areas where people exist on varying terms instead of Air’s sterile offices. Street Smart’s images and music portray a time and place where people live instead of an image to be bought.

Otis Redding’s rendition of “My Girl” plays at a soul food diner and Aretha Franklin’s “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” soundtracks a scene at one of those flophouses where Fisher is finally seduced by Punchy — in his review, Ebert praises Kathy Baker’s work as being on the same level as Freeman’s and he’s absolutely right, she’s wryly charming, knowing without judging and realizing too late that none of this will keep her alive. Fast Black kills her after she talks to the DA; this is shortly after Fisher has been jailed for contempt of court because he refuses to produce notes that don’t exist. Fisher gives up the scheme but his ongoing association with Fast Black has the judge convinced his coming clean is just another lie. Fisher can’t even use the truth to get out of the jam his story has created, while Air builds to Vacarro’s triumphant persuasion. Because if the product is so powerful, the story of its selling is important too. A commercial for a commercial.

Affleck is no slouch, he makes sure to include allusions to Malaysian workers stitching shoes and Knight paying a designer an hour’s wages for the logo he built billions on, but allusions are all they are, things to signify that he knows that we know them and that now that we agree they’re known, they can be dismissed. At one point Strasser and Vaccaro discuss Bruce Springsteen’s “Born In The USA” and how its ringing chords overlay a message of despair; the song plays over the movie’s epilogue in another empty signifier. The American Dream is complicated, says the movie that makes sure to show via text and archival images that the American Dream worked out well for everyone, even the losers (“Phil Knight has donated over $2 billion to charity,” a title card makes sure to inform the viewer — how nice of him). This device is de rigueur for docudramas and biopics and those important fictions “based on a true story,” it’s a way for the filmmakers to flatter themselves for their accuracy (look how much we made the actors look like the people they’re portraying!) and to remind the viewer of the weight of the story — this really happened. How lucky you were to see it. It’s self-congratulatory bullshit in the best of circumstances and downright insidious here. Because the “real” footage is presented as the natural outcome of the fictionalized and sanitized and depersonalized depiction of history created by the filmmakers’ choices, a closed loop of triumph made possible by the Jordan-sized hole in its center. Vaccaro tells it backwards — the product makes meaning around emptiness, its story only about itself.

The ending of Street Smart is more blatant and mean in its manipulation, so I like it much better. Fisher finally gets out of jail but is under even more pressure from a murderous Fast Black — himself out on bail — to create an alibi with his “reporting.” So Fisher comes up with a different story. He tricks Fisher’s bodyguard/enforcer into paying off a sex worker and uses his “Street Smart” camera crew to film it, creating footage that appears to show the enforcer undermining his boss and going into business for himself — a death sentence. Fisher shows the enforcer the footage and tells him he’ll show it to Fast Black. The enforcer understandably freaks out. And when his unknowing boss swings by shortly thereafter, the enforcer shoots him full of holes. Fast Black dies shocked and confused, the enforcer is devastated and immediately arrested, and luckily Fisher is there with his camera crew to explain what went down in a “Street Smart” segment. “The streets here can be hard and rough and the justice meted out isn’t always the kind taught in school,” Fisher narrates, looking directly at the camera. “The court of the street found Fast Black guilty even if the court of the law did not. The streets speak their own language and for a man who trafficked in death and violence, the punishment dealt out tonight was as fitting as it was absolute.”

It’s a story that may not be happy but has a certain satisfying justice, and Fisher tells it like he had no role in making it happen. Air does the same thing and that’s what galls me, the way it reduces subjects of history to objects that exist to be sold, and acts like the selling is so natural and inevitable the only thing to do is celebrate it, as opposed to it just being the actions of salesmen. Affleck and company celebrate turning a man into a myth and taking away his face to do so. Fisher makes up a fake man and when that winds up overlapping uncomfortably with a real person, he manipulates events so that person is killed off in order for his story to have a happy — for him — ending. Street Smart is a cynical look at how stories are sold, but it’s nowhere near as cynical as Air’s upbeat and empty history as product.

*it is darkly funny how this plays now — while Fast Black turns out to be a very bad dude, being introduced as “seeing a guy abusing a woman and kicking him in the junk so hard he dies” makes him appear nigh-heroic despite his occupation

**although he’s at least going after low-level corruption like crooked taxicab inspectors

***the film was a passion project for Reeve and to convince Cannon to pony up the financing, he agreed do one for them – Superman IV: The Quest For Peace

****there are also musical cues from 80s movie scores, which is just the dweeb version of using the radio bangers