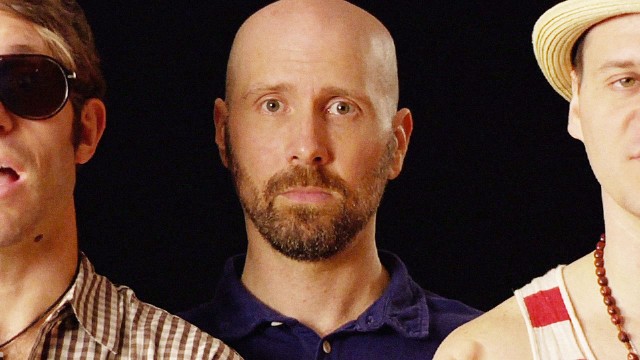

Mid-life crises, though common, are rarely pretty. It doesn’t help when one puts their neuroses out in public for everybody to see. Director and subject David Thorpe, a published journalist, just broke up with his boyfriend and has a cinematic breakdown of self-loathing over being in his 40s and single. To ease his pain, he goes to one of America’s gay meccas, Fire Island, and finds that he can’t cope with his catty effeminate community because he’s so irritated because he’s single. Like any logical person, he decides that what he actually can’t stand is the “gay voice,” and sets out to dissect it while trying to make himself more macho in the process.

Do I Sound Gay? is half a cultural dissection of coding and societal expectations, and half David Thorpe trying to keep his dignity while going through a prolonged period of stereotypical self-loathing that might have been more interesting if he had just bought a car and scored a gold digging boy toy for his rebound. The best metaphor for the movie comes from within the movie itself: David Thorpe frequently shows pop culture examples of historical gay voices (e.g. Liberace, Paul Lynde), and then talks directly over the clips to show how close, or not close, his voice is to these examples, simultaneously obliterating our chance to listen for the various intonations that have been revealed by his various linguistic experts.

The cultural dissection half, despite David Thorpe’s attempts to neuter the topic, is full of fascinating topic starters. Voice experts comment that what we consider the “gay voice” is actually coded as feminine through microchanges such as holding sounds and vowels for longer than men do, inflecting the end of sentences to go up instead of down, and having a more high-pitched and nasal tone than a chest-deep Voice of Commanding Masculinity. One of the key examples of whether the gay voice is actually a legitimate code is the comparison of Thorpe’s gay friend who grew up in a family of brothers and men, and his straight friend who grew up in a community dominated by women. The gay man has a barrel deep voice of cliche heterosexuality, while the straight friend sounds exactly like a Friend of Dorothy.

Thorpe has a variety of insights into the gay voice, and how it is read in both the heterosexual communities as well as the masculinity-obsessed homosexual community. A frequent canard of the masculine for masculine trope is “I’m not gay so I could have sex with a woman,” which is also seen as a source of pain for the very gay-voiced David Thorpe. Instead of diving deep into the misogynist undertones of these processes, Thorpe skips the view back onto himself, wondering if the deep voice doesn’t also make him weak in the knees and what that means about him.

Even though Thorpe has a broad array of social observers ranging from Dan Savage to David Sedaris, and an array of linguistic experts, he never gives any of them enough screen time to fully develop any one idea. As a result, Do I Sound Gay? is a skin-deep examination of cultural signifiers and subconscious community behavioral changes that serves as more of a conversation starter than a legitimate reference guide. This half is like a middle school research report. The real meat of Do I Sound Gay is an examination into the male psyche in the middle of an emotional crisis and the detrimental effects of how social pressure turns into self loathing. In the face of SCOTUS’s ruling of gay marriage, does that mean that gays are going to be pressured into marriage? Will we have boring midlife crises like straight men do? Do I Sound Gay? points out that these answers might be, unfortunately, yes.