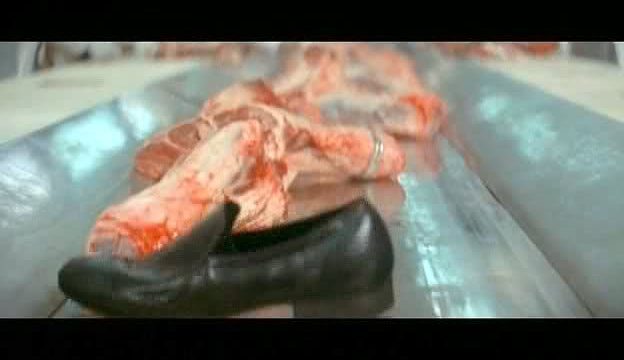

Prime Cut’s opening credits play over cows lined up for slaughter. There’s a naked male body among the them. The supervisor known later as Weenie (Gregory Walcott) smirks at the hairy ass from under his rumpled Kansas City Royals cap and continues the rendering process. Accompanied by anodyne Muzak, the montage cuts between the stages of disassembly from full cattle to ground meat.

Such is the way 1972’s Prime Cut treats flesh, a commodity made palatable for consumption by a slick and largely hidden system. The human body in the opening belongs to the member of a Chicago gang come to Kansas City to collect on a loan. After his remains are sent back to Chicago as hot dogs, Nick Devlin (Lee Marvin) is sent to find the responsible butcher, Mary Ann (Gene Hackman), and collect payment. Nick’s an outsider and outgunned by Mary Ann. He’s played by Lee Marvin which helps him in the end, but not before he’s seen the depths of Mary Ann’s depravity.

Charles Taylor writing about the film for the Los Angeles Review of Books in 2015 elucidates the movie’s theme with a clarity that only improved in the years to come:

Prime Cut is a sardonic report from the battle to define what America was and who it was for. It sums up not just the American separatism that had already reared its head — Nixon’s Southern strategy; the murders at Kent State; hardhats beating up protesters in lower Manhattan while stockbrokers cheered them on — but anticipates the yahoo rhetoric that was to come. In his 1980 campaign, Reagan was to revive the segregationist creed of “states’ rights.” In 2008, Sarah Palin would campaign on the notion of the “real America.”

If only the whole film was as streamlined as this summary. Taylor is being charitable when he describes the movie operating “in an oblique, foxy manner” instead of as satire buried in silliness. Prime Cut might be a movie with something to say about America during systematic slaughter in Viet Nam, but what sets it apart from the era’s other films preoccupied with violence is its willingness to plunge whole hog (or steer) into batshit lunacy. Like Paddy Chayefsky was commissioned to write the scenario for an early Daffy Duck cartoon.

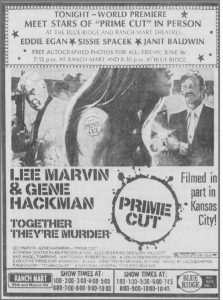

Still, Taylor nails the subtext of the thing. Prime Cut looks like, especially in its advertising, another hardball crime drama following in the wake of The French Connection. Certainly Marvin brings that sort of gravitas. But he’s up against Hackman as a goofball hillbilly underworld boss named Mary Ann almost certainly in an incestual relationship with his brother Weenie while running a meat packing plant and an orphanage whose young virgins he drugs and auctions to brothels. There’s probably a deliberate statement about 1972 America in those sentences, but as with Mary Ann’s meats the challenge is in using every part.

The Kansas City Star laughed it off: “A thriller with the humorous, cockeyed quality of last night’s dream remembered.” Many contemporary reviewers didn’t take the movie seriously enough to engage it on any kind of meaningful political level. The scattered positive notices generally appreciated its unique take on crime films and morbid humor. Detractors found it a surprisingly unpleasant action pic and shared the Chicago mob’s hostility at having a middle finger sticking out of the sanitized bundle of blood they expected.

The Star’s Mary Ann-like dismissal of the film wasn’t unique but carries some extra weight because of Kansas City’s prominent role in the movie. One would expect Nick’s big city know-how to have some currency. But the Kansas City of Prime Cut is a different kind of Midwest city than Nick’s Chicago. It’s much closer to the rural element of the nation, a concrete oasis in the crops. There’s a deliberate association between rural America and its county fairs, fields of grain, etc. and Mary Ann’s blithe cruelty. Nick first encounters him at one of his virgin auctions where bidders inspect the doped-up girls kept nude in livestock pens.

Prime Cut filmed for a few days in and around the Kansas City area, including scenes at a county fair in nearby Lawrence, Kansas. The local Journal-World, reacted with curiosity when it learned the fair would be “the ‘location’ setting of a feature film.” Their source reports “the title of the movie hasn’t been decided” and “isn’t sure just what the plot is.” One senses some deliberate omissions on the part of the producers.*

One year later the paper’s intrigue soured to irritation when the film was released. The paper didn’t employ a critic at the time, but its editor took on the mantle in an item headed “Prime Junk.” In addition to praising (twice) the uniforms of the Lawrence High School marching band featured in the movie**, the editorial declares it “generally an insult to the people of the area.” Before decrying the waste of Marvin and Hackman’s talents, the paper takes umbrage at Prime Cut’s depiction of its readership: “The film is billed as something of a fantasy or a ‘cartoon’ version of gangland warfare. Many viewers will see it as an insult to the kind of people who live here and as another move to picture this region as inhabited by bumpkins and hicks.”

And, yes, there’s plenty of city slicker gaffes to stick in a good Kansan’s craw. In a central action scene, Nick and rescued prostitute Poppy (a young Sissy Spacek) run through a wheat field from a combine intent on running them down and bailing them, the agriculture version of hot dogging one’s enemies. The machine bears down on them in something between a recreation and a parody of the crop duster scene in North by Northwest. Nick’s gangland cohorts finally ram a car into the combine and shoot its driver. The unmanned combine stalls, then consumes the whole vehicle, shitting it in pieces behind it.

Combines are not particularly deft machines, making the premise of the chase almost as dumb as a similarly lateral-blind scene in 2012’s Prometheus. There’s also baffling flourishes like the gangsters in the back seat coordinating their tumble out of the car (“Now!”) for no discernible reason (the driver stays put). But for all that, the scene as presented is actually pretty tense. And the final image, a hubcap bailed to a block of straw, reveals the film was – on some level – in on the joke.

The Lawrence editor, in addition to the disregard for the capabilities of farm equipment, also took issue with the portrayal of locals as “bumpkins and hicks.” “The people of this area are generally pictured as mindless rubes who are big, silent, obedient to the master, wear bib over-alls and carry shotguns to protect their ruthless cattle baron.” This is true. Before being pursued by one of these obedient rubes and his combine (did he fire it up when he got word they escaped the fair? Or just see a guy in a suit and act on instinct?), Nick and Poppy had to escape the county fair where every rifle-armed person at the sharpshooting booth took aim at them. Later comes Nick’s final assault on Mary Ann’s compound where he guns down several denim-clad minions, like the casts of the recently cancelled Green Acres and Hee-Haw ran off their sets to go work for Mary Ann. Prime Cut‘s hicksploitation elements beat contemporary rivals in quantity and the purity of their hickosity if nothing else.

The Lawrence paper, for all its complaints, does not mention the violence and sexuality in the film. It’s not a prude complaint. And it was likely written very aware it would be printed alongside stories about a nation embroiled in an endless foreign conflict, daily receiving the pulverized bodies of men. The complaints with the movie are 1) wheat is implied to be ready for harvest in June, 2) a combine could not eat an automobile, and 3) the fine people of Kansas are drones in service of an amoral leader.

Tough to say if fixing things like points 1 and 2 would have bought more consideration for item 3. If Prime Cut may have been a “sardonic report from the battle to define what America was” as Taylor says, a fearful warning about the corruption of Midwest values. But it’s a warning aimed from outsiders to other outsiders. For Kansans, it’s tough to take advice about your business from a source obviously unfamiliar and unconcerned with the particulars of your business.

Much as it would have been nice for the movie to inspire the furrowing of brows and consideration of the assumptions of political alliances, this machine isn’t built to consume that kind of heaviness and be taken seriously. The ending is a triumphant action punch that keeps it in a category apart from the more fatalistic 70s movies before and after. The film offers and then ignores some timely advice. There’s trouble brewing in the Heartland. Ignore it at your own peril.

* Also a hot air balloon was to be installed by the film crew “with some mysterious relation to the plot of the movie.” This was later cancelled without explanation but I like to think the original plan was for the combine to battle and chew up a hot air balloon in addition to the gang’s sedan.

** The same high school band was asked to appear in another film shoot in Lawrence just two years later. Wary school officials, feeling burned by the producers of Prime Cut, asked some questions this time and ultimately turned down the chance to appear in the softcore porno Linda Lovelace for President.