Walt never did like the motels and souvenir shops and so forth that sprang up around Disneyland after its opening in 1955. Oh, I’m sure that, from a financial perspective, it would have been awfully nice to have only Disney properties providing access and therefore getting tourist dollars. But Walt also genuinely regretted having created the landscape that surrounds the park where once there had only been orange groves. When it came to the second Disney park, they would not have that happen again.

An early study of Disney visitors showed that only five percent of visitors came from east of the Mississippi, which was at the time where three-quarters of the US population lived. The obvious solution was to build a second Disney park on the other side of the country. This time, however, the land would not be purchased openly. Disneyland was an expensive gamble; a second park would be more of a sure thing. This time, Walt wanted more secrecy—not least because the landowners would send prices through the roof if they knew they could get Disney money for them.

Much of the land in that part of Florida had already been part of a speculation grab, back in the 1920s. The Marx Brothers film The Cocoanuts is set during the Florida land boom of the time, when people were taking advantage of the idea of Florida as a winter home for the wealthy. World War I had made the Riviera a less desirable winter home, and Florida was closer than the West Coast. The bubble burst, and it’s entirely possible some of the people who sold their land to Disney had lost a fair amount of money in it.

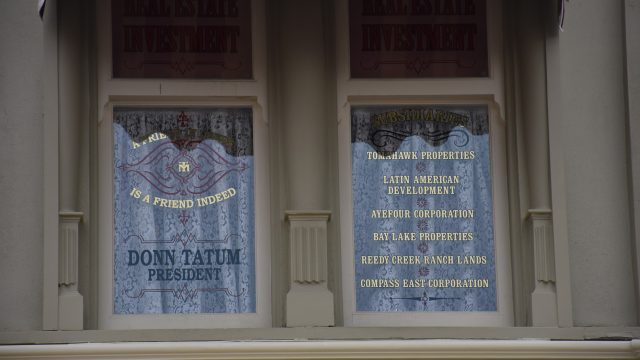

Of course, unlike that boom, there were ready-made buyers for the Florida land Walt wanted. Even if Disney as a company didn’t need it, you don’t have to go far outside the land the company bought to see the sort of thing Walt was trying to prevent from the immediate vicinity of the park. While rumours began spreading early—after all, you can’t not notice when you and everyone in the area has been selling land—not even the real estate agents knew who their actual client was. Speculations ran from NASA to the Rockefellers to Howard Hughes.

What actually confirmed the story for reporter Emily Bavar was apparently Walt’s lack of a poker face. She was at the tenth anniversary of Disneyland and asked Walt if he was behind the land purchases in Florida. Talking about it later, she said he “looked like I had thrown a bucket of water in his face.” He denied it, but she ran the story anyway. Fortunately, I guess, Disney had bought the land they planned to by that point, and the story was confirmed only a little before the planned official announcement.

Still, one of the strangest aspects of the whole thing is that the mineral rights to the land were not, generally, held by the actual owners of the land. Instead, they were held by Tufts University. I do not know why this is true. I don’t even know if they would have raised their price if they knew they were dealing with Disney—who, in fact, to this day has not developed quite a lot of the land, as one of the things Walt wanted was a wildlife preserve. But still.

Even weirder, it’s technically in Disney’s contract that they can build a nuclear reactor on their land. It wouldn’t surprise me if this had to do with Walt’s futurism; there’s a lot of stuff from around that era about Our Friend the Atom and all that. I’m also honestly a bigger fan of nuclear power than a lot of people, and it’s not as though Disney would be as incompetent with it as the former Soviet government—though Fukushima proves you don’t want a nuclear power plant at such a low elevation. Mostly, it’s that the contracts Disney has with the State of Florida mean that they can do pretty much whatever they want on their land. But the idea of Disney’s Nuclear Option can go a lot of places.

Today was supposed to be Year of the Month, but who can resist an anniversary? Celebrate by contributing to my Patreon or Ko-fi. Today’s image is from Anthony Pizzo.