‘Depth’ is something that everyone recognises as a good thing, and what everyone wants to see in the art they consume* – I remember, with some embarrassment, defending the depth of Gears Of War and what it was saying about war when I was seventeen. But it’s also something people find difficult to define, which I think comes from people using the same word to describe two entirely separate reactions. I think when people use the word ‘deep’ to describe a work, they’re describing either an intellectual reaction or an emotional one, and I think when I was frenziedly defending the depth of a video game in which you can chainsaw aliens in half, I was doing what a lot of people do, and trying to fashion the latter into the former.

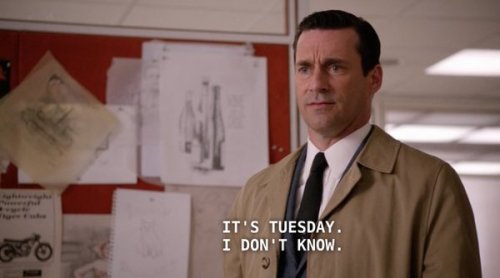

The way most people use depth is to describe that intellectual reaction – that there is something this work taught us about the world. The Wire teaches us about the systems that make up 21st century America. Mad Men teaches us about the connections between corporate America, the counterculture of the Sixties, and the human condition. It’s more obvious in weaker works trying to be deep – either they’re incorrect, or they’re obvious to the point of triteness – and, of course, what’s novel and interesting to one person is obvious or trite to another.

On the other hand, you have emotional depth, which I think is when a work hits a specific emotion – the more specific the better. This is the kind of depth The Simpsons traffics in – the ending of “And Maggie Makes Three” and “Lisa’s First Word” conveying the joy of fatherhood, for example, or “Lisa’s Substitute” conveying the despair and hope of being a gifted child in a world that doesn’t seem to care about that. It can also apply on a longer scale, too – Mad Men is dronelike in terms of tone, and the basis of that drone is warmhearted humanism, which is something I respond to really positively; on the other hand, I’m told part of the appeal of The Sopranos is its bleak, fatalistic despair. Emotional depth is easier to recognise but harder to quantify, especially in terms of practical value, and I believe that comes from the fact that its value lies in showing us a familiar feeling and comforting us with the idea that we are not alone.

There’s a third idea here, though, and that’s things we can recognise as good but not deep. Most people, first watching Cowboy Bebop, recognise that it’s fun to watch and a little strange, but even the most hardcore fan will tell you that falling in love with it is a slow process, where you get about half a dozen episodes in and realise you’ve grown accustomed to its face. I believe this is because it deals primarily in sensation, distinct from emotion; where The Simpsons or The Shield deals in joy and fear and anger, Cowboy Bebop deals in vertigo, adrenaline rushes, and hunger, with the emotional depth more carefully parceled out. This is the easiest reaction to recognise of all, and also the one most likely to be dismissed as unimportant. For sensation to be seen as deep, it has to be framed by either intellectual or emotional structure – such as in the films of Martin Scorsese, sensation framed by morality.

My initial interpretation of Gears Of War was a simple logical error – deep things are good, this is good, therefore it’s deep – that came about because I was upset over a perceived insult to something I liked. Removing the need to prove it fits one specific interpretation of ‘good’ means more clearly understanding and articulating what I actually get out of the game: ownage, connected to a sense of camaraderie, in a universe that cannot be taken seriously. I learn more by taking the story for what it is and does, rather than what it should be or do.