The reviews are beginning to come in for David Fincher’s newest film, Gone Girl. The film, a relationship drama-murder mystery-psychological thriller, is adapted from Gillian Flynn’s novel of the same name. Flynn’s Gone Girl was a commercial hit, a best seller, but was absent from prestigious literary awards and honors. It is, as they, “an airport novel,” the kind of book that sells well, but also tends to leave critics lamenting the fact that it sells well.

Gone Girl‘s apparently disreputable literary origins have disappointed some film critics, who see it as “beneath” Fincher as an artist. For instance, Todd McCarthy at The Hollywood Reporter wrote that:

“David Fincher’s film of ‘Gone Girl,’ Gillian Flynn’s twisty, nasty and sensational best-seller, is a sharply made, perfectly cast and unfailingly absorbing melodrama. But, like the director’s adaptation of another publishing phenomenon, ‘The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo,’ three years ago, it leaves you with a quietly lingering feeling of: ‘Is that all there is?”

One critic, Michael Nordine at IndieWire, saw the situation similarly:

“It’s hard to shake the notion that he could be doing something more rewarding than becoming the preeminent director of airport-novel adaptations, a trajectory that’s all the more disappointing after the trifecta of ‘Zodiac,’ ‘The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,’ and ‘The Social Network.'”

These criticisms trouble me.

They trouble me because this kind of rhetoric is both willfully ignorant of Fincher’s prior output, and betrays a kind of snobbery that is unbecoming of a critic. If we were to accept and buy into these critics’ assertions, then we would need to buy the notion that David Fincher had sold out and given his talents over to middlebrow adaptations. But such a concept would only make sense if one were to ignore or imagine away Fincher’s previous films. Taking a closer look at Fincher’s filmography should disabuse that notion.

What are Fincher’s most acclaimed films? Probably Zodiac, Fight Club, and The Social Network. Fight Club was dubbed “The Greatest Film of Our Lifetime” by the magazine Total Film (which should tell you a lot about Total Film’s presumed readership). Within a few years of its release, Zodiac ended up on several “Best of the Decade” lists. And The Social Network was an outright awards and critical darling.

Fight Club might have been considered, in 1999, as coming from a relatively “high cultured” pedigree, but come on — Chuck Palahniuk is a machismo-fixated hack scribbler whose books were only elevated to their once-lofty position because his indulgent writings appealed more a male audience than a female one, and even that appeal quickly wore off.

The Social Network? Let’s recall that the film is based on Ben Mezrich’s gossipy tell-all whose full title (The Accidental Billionaires: The Founding of Facebook, A Tale of Sex, Money, Genius, and Betrayal) equally emphasizes the flavor-of-the-month-so-let’s-get-this-thing-out-before-people-are-sick-of-Facebook quality, the promise of tawdry sex, and the melodrama inherent in such words as “genius” and “betrayal”.

And Zodiac…well, I’ll get to that later.

And what about his other films? An Alien sequel no one particular wanted. A couple of slick, movie-star-driven action thrillers. Buddy/buddy detective movies with flashy serial killer villains (one of which was actually based on an airport novel). A love story that many found to be a repeat of Forrest Gump.

You might be thinking, “No! How can you be so glib about so many wonderful movies? I love Seven! The Game is great!” And you’d be right. It is not only belittling, smug, and altogether wrong-headed to judge a film based solely on its origins, it also reveals an ignorance, either of willful or simply out of carelessness, of the history of film. Mario Puzo’s The Godfather was not Dostoevsky. Peter Benchley’s Jaws didn’t launch him to the status of Nobel laureate.

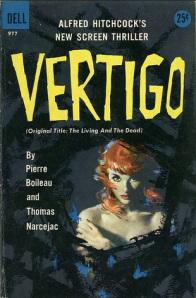

And what about Vertigo? Alfred Hitchcock’s masterpiece? Y’know, the film that hundreds of film critics and writers around the world recently found to be the greatest cinematic achievement of all time?

Furthermore, I wonder why these critics who condescendingly write “Little David needs to apply himself in class” on Fincher’s metaphorical report cards think that he has some secret desire to break into the presumably very exclusive club of avant-garde art filmmakers. This is the man who, in addition to the films mentioned above, has pitched Spider-Man movies and a big budget blockbuster version of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea starring Brad Pitt. I bring this up not to criticize Fincher, not by any means, just to say that every one of the man’s films has been in the area of commercial possibilities and mainstream accessibility. Does he make bold, interesting choices? Absolutely! Does he do them within the frameworks of airport novel adaptations, buddy cop movies, and Michael Douglas-is-in-Yuppie Hell thrillers? Yes! Just as Alfred Hitchcock became a favorite of the cinephile set through his consistent and consistently entertaining craftsmanship, regardless of the fact that his movies initially appeared, on the surface, quickie Hollywood trash, so Fincher has made his name not through brazen experimentation, but through confident, assured, and downright effective direction.

If either have to get on board with that, and evaluate based on his filmmaking, that is to say, on the films themselves, or you stop talking about him until you understand what he’s doing. You can be critical, but not reactionary. To act otherwise does you a disservice greater than any disservice Fincher does to you, or you to Fincher. Judge his work as it is, not against some imaginary body of work that exists only in your imagination.

Oh, yes. One last thing. Recall, if you will, the final scenes of the film Zodiac, perhaps Fincher’s greatest accomplisment so far. After 22 years of mostly fruitless investigation, the only Zodiac Killer survivor to have seen his assailant’s face is finally brought in to look at photographs of Zodiac suspects. It’s a brilliant scene, directed by Fincher with great, quiet tension and more than a pinch of restrained catharsis. But just moments before this, we see the new lead detective be lead through the airport terminal where this identification is taking place.

And for just a second, he passes by a rack of books — airport paperbacks, the kind of book that sells well, but also tends to leave critics lamenting the fact that it sells well. The book? Robert Graysmith’s bestselling Zodiac, the book that Jake Gyllenhaal’s character has spent the entire length of the film researching and writing, the very book that the film is based on.

Fincher knows who he is, and what he is, and where his movies come from. And he’s not ashamed of it, not afraid to show us. Get with it or get out of the way, for here marches David Fincher, King of the Airport Novels.