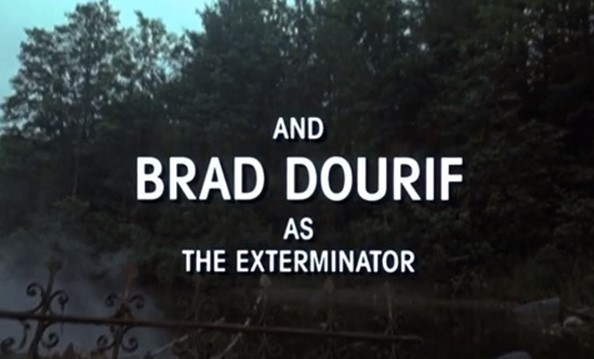

I like looking for names in the credits. I had been scrolling through HBO’s library before selecting Graveyard Shift, a not-very-well-regarded Stephen King adaptation that turned out to be a damn good time, and was immensely cheered during the opening credit sequence to see “and Brad Dourif as The Exterminator” was coming my way. And then another familiar name popped up – one of the casting directors was Sharon Bialy. This is a fairly early credit for Bialy, although she had already helped cast the Dourif-starring Child’s Play and was about to work flicks chock full of great actors like Point Break and Diggstown. But where I knew her name was from credits on TV, in particular Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul. She’s a person who excels at finding the right people for the job.

She’s also casting director for the TV show Barry, whose third season I just watched on HBO Max*. Barry doesn’t have an opening credits sequence, just a title drop after the first scene, and the end credits – where you would see Bialy’s name, and the names of the actors she cast, and the crew that filmed them – are considered pretty optional by the streamer. If you want to watch the entire credits, you have to stop autoplay from skipping them on the way to shoving the next episode into your eyeballs.

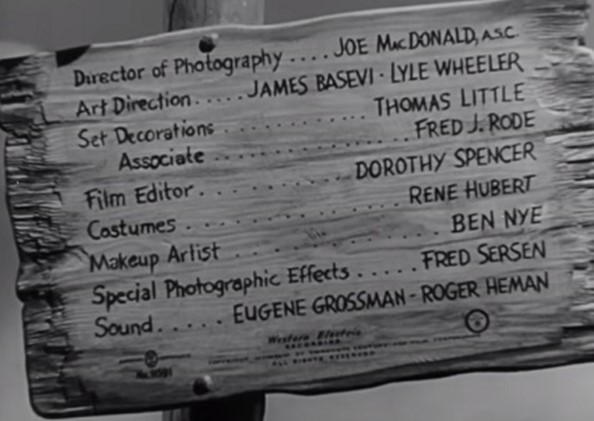

The more old movies I watch, the more fondness I have for the extremely blatant opening credit sequences – instead of the current standard of text layered over moody footage of the in-process film, the credits here are unapologetically separate signposts (literally, in the case of My Darling Clementine) of people who made the movie. Well, some of the people who made the movie. Did My Darling Clementine have a key grip, a best boy, stunt performers, drivers? None that we would know of.

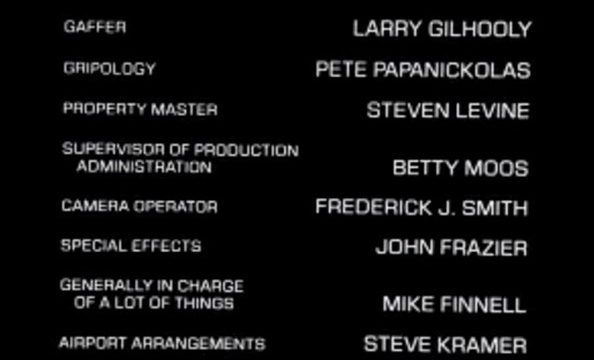

Credits don’t always credit everyone, of course. End credits didn’t even exist as a standard practice until about 60 years ago. But they’ve become more comprehensive over the years, I think. This has provided the opportunity for jokes – the ZAZ movies excel at this, like crediting “Charles Dickens” as “Author of Tale Of Two Cities” in Airplane!, although my favorite gag is the Coens’ disclaimer that “No Jews were harmed in the making of this movie” at the end of A Serious Man – but also a bounty of information. The credits are a way to note trends via fashion designers acknowledged or to confirm locations from local officials thanked. They’re a way to track careers – hey, it’s Bill & Ted and Don’t Tell Mom the Babysitter’s Dead director Stephen Herek as an apprentice editor in The Slumber Party Massacre! – and to mark the work of the dozen video effects teams for the latest blockbuster. For all of Marvel’s sins, their post-credit scenes have actually encouraged viewers to sit through the scroll of names responsible for the movie they just watched, if only to get a 30-second glimpse of Nick Fury glowering at a glowing egg or some shit.

I’m not clear on the rules around credits and their airing, but I know some rules must exist that demand their presence. Anyone over the age of 30 can recall a movie airing on network TV or basic cable and ending with its credits airing in half – a quarter? An eighth? – of the screen while the next program or the local news is teed up in the main slot. This has become more aggressive over the years, with the credits airing in near-subliminal flashes while How I Met Your Mother begins in the majority of the screen, but there’s something perversely comforting about how, despite the network’s clear desire, they can’t excise the credits entirely.

But streaming is something else. And while I crapped on the standard minimalism credits for movies these days above, that style does at least continue the integration of credits into the body of the film, making it impossible to cut them out without savaging the work itself. That doesn’t hold for TV and especially TV on streaming. Even though it is easier than ever to skip ahead on a stream (especially compared to something like a fast-forwarded VHS), HBO and Netflix and the like have little buttons popping up during both the opening and end credits, telling you to cut them out entirely. That’s if they’re not autoplaying past those credits in the first place. Why is that?

There has been a lot of talk about AI entertainment lately. ChatGPT can write scripts, Midjourney can create images – those computers can do it all! Except they need human prompts and, more crucially, require human-created data to generate this work. Telling a program to create a fake David Cronenberg movie requires it to know what a real David Cronenberg movie looks like, and therefore a real David Cronenberg to make one in the first place. But while that fake movie uses Cronenberg as an idea, it doesn’t compensate him in any way. It doesn’t allow him to make more art. It steals and, even worse, the act of stealing trains it to steal better in the future. To make “content” – let’s not call it art, with no effort or humans behind it at all. This of course will be delivered via algorithm, based on what you previously watched, as opposed to searching something out for yourself. I think if I watch nonhuman works delivered in nonhuman ways for a while, I’ll become less human myself.

I’m still human enough to be paranoid now, and the streaming credit erasure strikes me as laying the groundwork for all this. The people who made the show do not matter at all, what does matter is the show as continual flow, content that keeps coming at you without interruption or consideration of how it was created by a bunch of actual people doing actual work. Once you take away that recognition, why be concerned if people make the art at all? Because if you don’t care about that, then you won’t care when it’s just some robot ejaculating vaguely acceptable images and words into your face because Reed Hastings typed “heartwarming dystopian teen drama in the style of John Hughes without the racist jokes” into the prompt field. You won’t even notice the change. And if art helps tell us who we are, maybe without it you won’t even remember your name. Let alone Brad Dourif’s.

*Barry is a show in part about Hollywood productions, at one point the main character meets with legendary casting director Alison Jones, who is playing herself – Jones actually has Bialy beat in the horror origins department, with her first credit coming for schlock crapsterpiece Hard Rock Zombies.