Last month, I discussed two film adaptations of H. P. Lovecraft’s horror stories, and I noted that in the earliest attempts to film Lovecraft’s stories his plots “were frequently changed, saddled with romantic subplots or altered to accommodate shooting locations and special effects budgets.” The films I had in mind were those directed by Roger Corman and his associates in the 1960s and released by American International Pictures. While the AIP films are quite free with the details of the stories upon which they are based (something hardly unique to the Lovecraft adaptations), they are entertaining in their own right, featuring performances from such horror icons as Vincent Price, Boris Karloff, and, uh, Dean Stockwell. Moreover, in reviewing The Haunted Palace (1963), Die, Monster, Die! (1965), and The Dunwich Horror (1970), one can trace patterns in horror—especially a change from gothic horror to science fiction and psychedelia—and in the elevation of H. P. Lovecraft from cult favorite to counterculture icon.

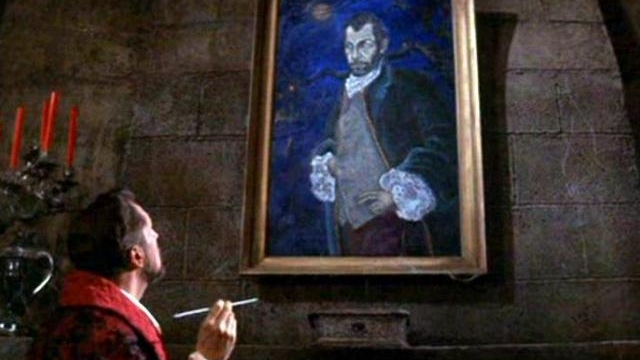

The Haunted Palace, the only one of the three under discussion directed by Corman, is nominally based on a poem of the same name by Edgar Allan Poe, but is actually a free adaptation of Lovecraft’s short novel The Case of Charles Dexter Ward. (Lovecraft is credited along with Poe, but in 1963 Poe’s name would have meant more to audiences, and AIP pushed to make the film part of Corman’s vaunted “Poe cycle.”) In the film, Charles Dexter Ward (Vincent Price) inherits a castle outside the remote New England village of Arkham, only to find that his ancestor, Joseph Curwen, is still remembered and hated by the descendants of the townspeople who put him to death for witchcraft a century before. Ward’s arrival stirs up bad memories of a curse Curwen laid on the town, especially since Ward looks exactly like the portrait of Curwen that still hangs in the castle.

Almost immediately upon his arrival with his wife Ann (Debra Paget), Ward’s personality begins to change, and instead of quickly selling the castle and leaving, as originally planned, he decides to stay and begins treating his wife with the same imperious contempt that he directs at the townspeople. Of course, it is Joseph Curwen, returned from death to take over Ward’s body with the help of fellow sorcerer Simon (Lon Cheney, Jr., posing as the castle’s caretaker), a development that is clear to the audience but which takes much longer for Ann or the friendly Dr. Willet (Frank Maxwell) to comprehend.

The Haunted Palace includes many elements common to Corman’s Poe cycle and that would be prominent in the AIP Lovecraft adaptations: it is rich in color and texture, and the castle itself is a character as much as a setting (Corman reused many of the sets and props for his Poe cycle, accumulating these hand-me-downs so that each film was more lavish than the last).

It’s especially notable for Ronald Stein’s gorgeous, throbbing score: like many directors working with limited budgets, Corman is sometimes accused of piling on dramatic musical stings to make up for underwhelming onscreen effects, but in this case the score works with the setting and performances to create an atmosphere of lush, eerie decadence. (Curwen’s passion for his busty mistress, not to mention his leering attempts to have his way with Ann, also inject a dose of sensuality that was foreign to Lovecraft but quite at home in B movies.)

The entire Poe cycle is notable for its psychological approach to horror: as Corman stated in his memoir How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime, “I felt that Poe and Freud had been working in different ways toward a concept of the unconscious mind, so I tried to use Freud’s theories to interpret the work of Poe.” This resulted in the (sometimes derided) long shots of characters walking down hallways, terrified but compelled to continue. Although Corman in the same book compares his method of building tension to the rhythms of a sexual act (continuing the Freudian interpretation), the internal conflict of characters who must know the truth, even if it will destroy them, is also at the core of Lovecraft’s fiction, and the technique is very effective here.

Still, the film departs significantly from Lovecraft’s original in many ways: there is no palace in the novel, only the farm that once belonged to Curwen. The film also reveals Ward’s ancestry right away, omitting Dr. Willet’s slow realization and mounting horror in the novel. Also missing are such scenes as Ward confusing his contemporaries with eighteenth-century argot and references to colonial citizens long dead. And as noted, the female presence is considerably bulked up in the film: not only is Ann an active participant in the plot (Ward is unmarried in the novel), the novel’s scheme of resurrecting the dead through their “essential saltes” is carried out in the film only as far as Curwen’s revivification of his dead lover (Cathie Merchant). Ultimately, the climax owes as much to “The Picture of Dorian Gray” as to Lovecraft’s novel, with the connection between the portrait of Curwen and his descendant’s psyche broken . . . or is it?

1965’s Die, Monster, Die! transplanted the AIP Poe formula to England; it was based on “The Colour Out of Space,” the story of a meteor and the horrible transformations it brings to the remote countryside in which it falls. However, the replacement of an impoverished farm with an English manor and the hapless head of the doomed family with a scientific researcher played by Boris Karloff pushes the film much closer to the hubristic tragedies of Universal and the rich atmosphere of the Poe films. First-time director Daniel Haller had served Corman as art director on many of his movies (including The Haunted Palace), and AIP clearly had the success of Corman’s Poe films in mind.

The film is serviceable as sci-fi horror but not terribly essential as cinematic Lovecraft: what is most notable is the deployment of occult trappings that are almost entirely irrelevant to what is actually happening in the story. This takes Lovecraft’s approach (in which “magic” is really the application of higher mathematics or alien superscience, an early approximation of Clarke’s Law) to its logical endpoint, but effectively makes references to Lovecraft’s own mythos into red herrings. As in The Haunted Palace, Witley Manor is hated and feared by the people of the surrounding town because of its previous owner’s reputation for black magic and sorcery, but Karloff’s Nahum Witley is a man of good intentions whose research is undertaken to help alleviate world hunger (and at least partly to clear his family name).

The meteor, which reduced the area in which it fell to a blackened stretch of ash (the “blasted heath” of Lovecraft’s original), is clearly a source of radioactivity, conveniently identified by hero Stephen Reinhart (Nick Adams), an American “science student” who visits the Witley Manor at the invitation of Witley’s daughter Susan (Suzan Farmer). Witley’s scheme is to reign in the meteor’s destructive power and channel it into growing super crops, but he is unable to protect his household (including his wife, and ultimately himself) from being mutated by prolonged exposure to its rays. In that sense, the fate of the characters is the same as in Lovecraft’s story, but the doomed attempt to channel the meteor’s power puts Witley in the position of a classic mad scientist. I’m sure that the historical resonance of Karloff’s final transformation into a green, lumbering monster was lost on neither the filmmakers nor audiences at the time.

A thread running through both The Haunted Palace and Die, Monster, Die! is the family curse, and more specifically the attempt to breed human women with the monstrous, alien outsiders of the Cthulhu mythos: in Lovecraft’s fiction, such elements are prominent representatives of the author’s fears of both inbreeding and miscegenation, sometimes made explicitly racist and sometimes cloaked in elaborate metaphor. In The Haunted Palace, Joseph Curwen’s abduction of village maidens is an update of the “virgin sacrifice” trope, an excuse to place a pretty girl in bondage and threaten her with rape by a none-too-convincing monster, nearly incidental to the plot; the deformities that continue to plague the citizens of Arkham are not a result of Curwen’s parting curse but a legacy of his crossbreeding experiments. In Die, Monster, Die!, the experiments of Witley’s ancestor are referred to but are ultimately misdirection, and the many monstrosities of the film (including a greenhouse full of animal test subjects grown gigantic and grotesque) are the result of scientific (or at least science fictional) processes.

In 1970’s The Dunwich Horror (also directed by Haller, and executive produced by Corman), the theme of alien parentage is front-and-center, and the scheme to find a new human vessel for the Old Ones to impregnate is the main story rather than a subplot. This is, of course, partly due to the choice of source material, in which those elements are strongly present, but the execution points to changes in the movie business and larger culture, as well as the changing perception of H. P. Lovecraft as a creator of “trippy” fantasy and horror.

As in Lovecraft’s story, the film centers on a young man named Wilbur Whately and his attempts to steal Miskatonic University’s copy of the rare and poisonous Necronomicon in order to complete an arcane ritual. The Whately family (like Curwen and Witley) is notorious for its practice of black magic, and Wilbur is simply attempting to carry on the work of his grandfather, who successfully summoned something from “outside” to mate with Wilbur’s mother, Lavinia. Also in common with the original story, the Whatelys conceal a monstrous secret which threatens the countryside when it escapes and runs rampant. Scholar Henry Armitage must use the information in the Necronomicon to undo Whately’s ritual and “close the gate” on the evils he hopes to summon.

In broad outlines, The Dunwich Horror is more faithful to its source than either The Haunted Palace or Die, Monster, Die!, and it attempts to portray ritual magic in a more accurate manner than usual, drawing from the practices and iconography of Aleister Crowley, among others. Unfortunately, the resulting film is slow-moving and uneven, and the freedoms it takes due to a more permissive Hollywood climate produce mixed results. In updating the story to 1970, the filmmakers sought to plug into the youth culture in a deeper way than simply casting young leads (as in Die, Monster, Die!): The Dunwich Horror recasts Wilbur Whately as a charismatic, disaffected young dreamer (albeit a sinister one) who captivates (and captures) his subject Nancy (Sandra Dee), drawing her into his web in hopes of recreating the ritual that led to his own conception. Much of the film’s running time is devoted to Wilbur’s seduction of Nancy, and although he makes her uneasy, there is something magnetic about him; as Wilbur Whately, Dean Stockwell bears a strong resemblance to charismatic cult leader Charles Manson: handsome and persuasive but with insanity shining in his eyes.

There are copious psychedelic effects: prismatic colors, dream sequences, and droning music. Some of these work well: the creature the Whatelys hide in the attic, realized with strobing colors and optical effects, is closer to Lovecraft’s conception of a monster half in and half out of the material plane, and which cannot be fully taken in by the human eye. Combined with shrieking sound effects and music, the creature’s appearances are almost always a shock, and do a good job of suggesting the feeling of seeing such a thing rather than attempting to depict it literally.

The Dunwich Horror is also more explicitly sexual than the previous AIP Lovecraft adaptations or (needless to say) the original story, mostly due to scenes of Nancy undulating sexually on an altar, her thighs and hips bare. (According to The Lurker in the Lobby: A Guide to the Cinema of H. P. Lovecraft, the film’s press kit made much of star Sandra Dee’s semi-nudity, emphasizing that the set was closed while shooting those passages, but director Daniel Haller recalled that a body double was used.) The film was nearly given an X rating.

In another sequence, Nancy has a troubling dream (or is it?) of a very contemporary orgy, filmed with a swooping handheld camera and edited like a disorienting drug trip: like much of the film, the sequence is indebted to the 1968 hit Rosemary’s Baby, but is much cheaper and tackier, neither scary nor erotic. In 1970, the answer to the question “What will scare the audience most?” was apparently “body-painted hippies!”

Ultimately, the popular meaning of horror had changed: personal and existential horror like Rosemary’s Baby was all the rage, and the classic monsters had become campy fun for kids. (Gothic horror was in a temporary slump in America, the torch being carried in Britain by such outfits as Hammer and Amicus.) As mentioned, Stockwell’s portrayal of Wilbur Whately bears a strong resemblance to Charles Manson; The Dunwich Horror was released in January of 1970, after the Tate-LaBianca murders but before Manson’s trial, so I am unsure how deliberate this resemblance is. As noted in The Lurker in the Lobby, Stockwell fit Lovecraft’s description of Whately as “goatish,” and Haller confirmed that Stockwell was already a Lovecraft fan (“Not that he was crazy or anything”): perhaps Stockwell and Manson both conformed their images to popular conceptions of the sorceror-guru in the air at the time.

Perceptions of Lovecraft were changing as well: Arkham House had been founded in 1939 to preserve the work of Lovecraft and his contemporaries, but its reach was relatively small; in the late 1960s, Lovecraft’s fiction was issued in paperback by such publishers as Lancer, Ballantine, and Beagle, reaching huge numbers of readers hungry for fantasy and horror, the weirder the better. By the time The Dunwich Horror was released, H. P. Lovecraft had already lent his name to a Chicago-based psychedelic rock band and would soon appear as a character in Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson’s sci-fi-cult-conspiracy novels. Comparing The Haunted Palace to The Dunwich Horror, it’s hard to believe that only seven years passed between them: in that time the world had changed, and the cult had finally gone mainstream.