Watching Stanley Kubrick’s documentaries, three short works from 1951 and 1953, you only see a few flashes of the filmmaker he’d become. You see someone doing a competent job with not much in the way of personality; you also see the good he took from the world of photography and some of the bad habits that mark his first two feature films.

What’s there right from the beginning (in the 1951 newsreel The Flying Padre, of which it can unarguably be said that it exists) is a photojournalist’s sense of great faces. Kubrick’s camera moves over crowds and settles on a face or two, or he just holds on a face in isolation. There’s nothing innovative about this; you can see it in many newsreels of the time. It’s a technique that dates back to the earliest days of photojournalism; I’m thinking particularly of Jacob Riis’ How the Other Half Lives (1910) and the great RA/FSA photographs of the 1930s. Possibly because Kubrick got his start taking pictures around his neighborhood, he had a lifelong ability to find the expressive face and use it. As I suggested with Killer’s Kiss, this might be the origin point of the way he chose actors for how they looked over how they could act–he began by filming people who were not actors.

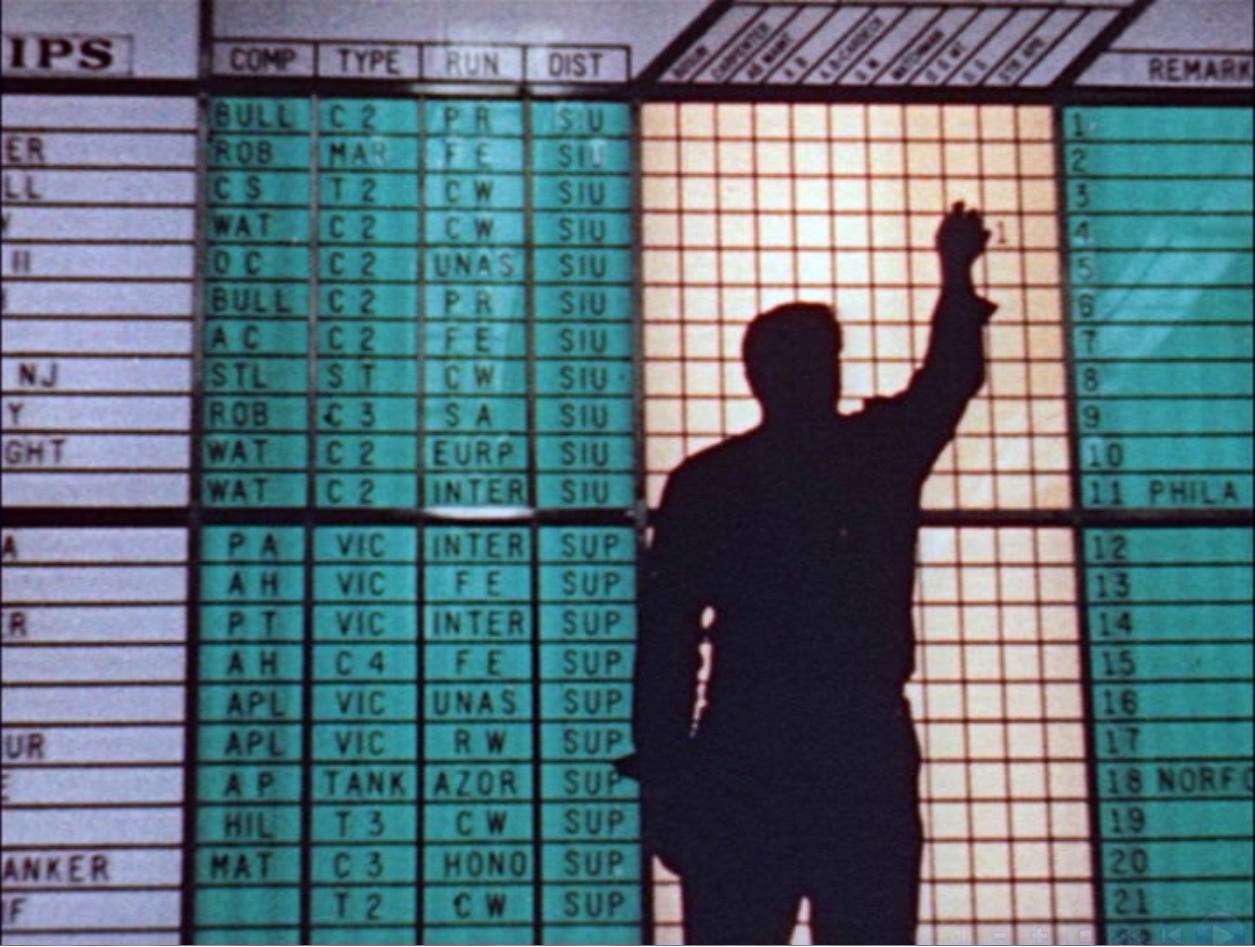

Kubrick made The Seafarers in 1953, not long after Fear and Desire, and it’s his longest documentary (almost half an hour) and, interestingly, his only color film until Spartacus. A recruiting film for the Seafarers’ International Union (SIU), it’s straightforwardly narrated by Don Hollenbeck (the suicidal CBS newscaster in Good Night, and Good Luck) and edited in the what-he-says-is-what-we-see school. It’s largely uninspired, which makes the moments when you get some stunning compositions even more effective:

If you’re looking for them (and I was), you can see some future elements of Kubrick in The Seafarers. He edits with a distinct rhythm of alternating crowds and single people or couples in a way that feels early-Soviet; one could argue that this is the theme of the film, an individual finding power with the community. (I think it looks cool and generates a good rhythm if not a good pace for the viewer.) There are the great faces, of course, but there are also more images of objects than would be necessary; seeing a bunch of adding machines in all their 1953 glory was a nearly surreal moment (it felt like footage from Koyaanisqatsi had gotten spliced in), and at one point he pans over a model ship on a desk just as he would a real ship in a harbor. The objects are framed with a touch more space than anyone else would give them, making the images more contemplative. That feeling extends to the rest of the film; the voiceover is slower and more repetitive than it needs to be, and scenes feel like they extend too long. Charitably, this could be Kubrick experimenting with pacing, leading to the great slow works of his later career; realistically, I’m thinking he had 24 minutes of material and was under contract to deliver 30.

If you’re looking for them (and I was), you can see some future elements of Kubrick in The Seafarers. He edits with a distinct rhythm of alternating crowds and single people or couples in a way that feels early-Soviet; one could argue that this is the theme of the film, an individual finding power with the community. (I think it looks cool and generates a good rhythm if not a good pace for the viewer.) There are the great faces, of course, but there are also more images of objects than would be necessary; seeing a bunch of adding machines in all their 1953 glory was a nearly surreal moment (it felt like footage from Koyaanisqatsi had gotten spliced in), and at one point he pans over a model ship on a desk just as he would a real ship in a harbor. The objects are framed with a touch more space than anyone else would give them, making the images more contemplative. That feeling extends to the rest of the film; the voiceover is slower and more repetitive than it needs to be, and scenes feel like they extend too long. Charitably, this could be Kubrick experimenting with pacing, leading to the great slow works of his later career; realistically, I’m thinking he had 24 minutes of material and was under contract to deliver 30.

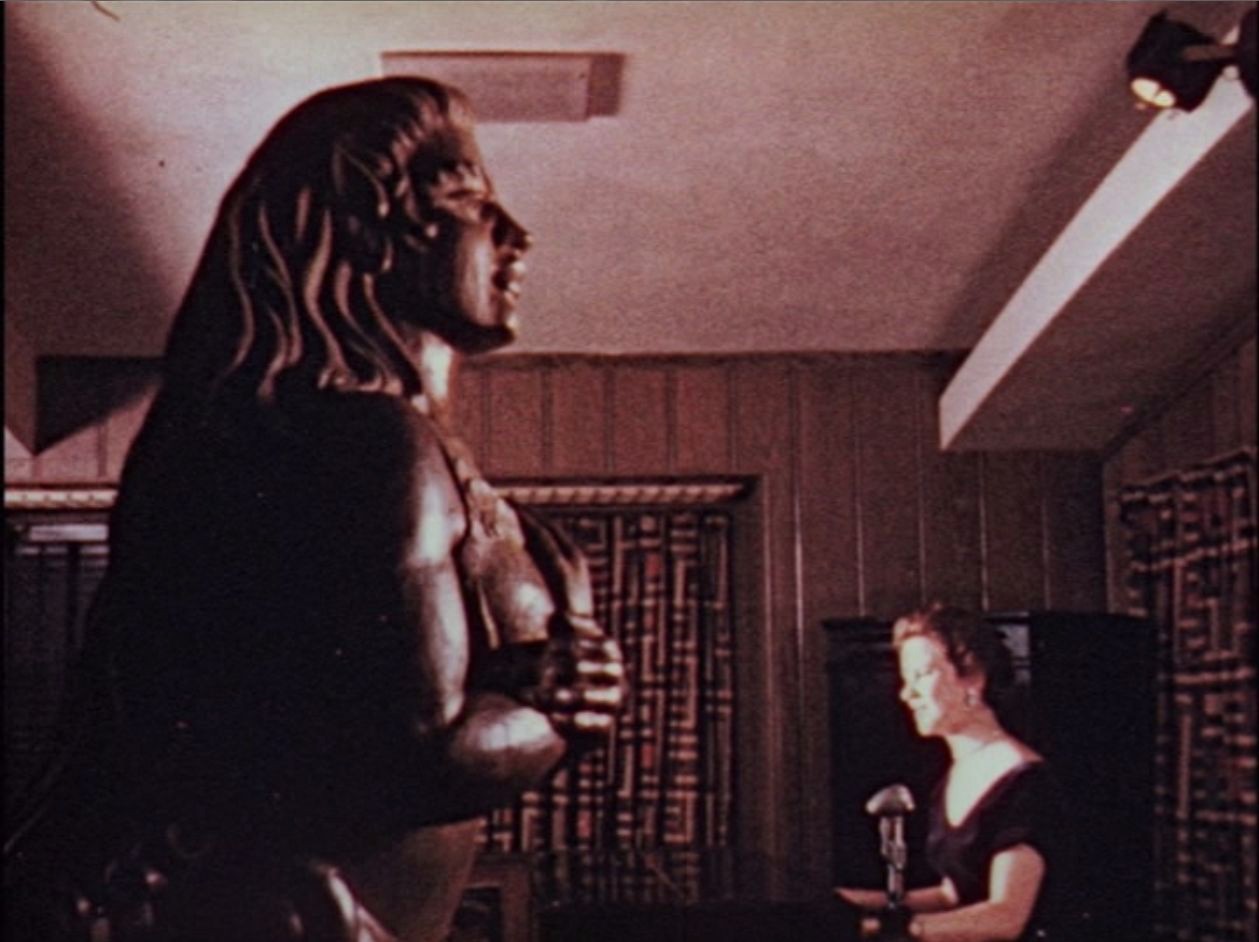

Day of the Fight (1951) has the strongest fit in the Kubrick genealogy, deriving from his 1949 picture story “Prizefighter” for Look magazine and leading directly to the first fifteen minutes of Killer’s Kiss, which restages some scenes from the documentary. (The fighter checking out his features before the fight like he’s putting on makeup appears in both, and both times it has a strong feeling of something real that we haven’t seen before.) Like the title says, it tracks the events in the hours before a fight for one fighter and his manager/twin brother, with the voiceover emphasizing (a lot) that the waiting is indeed the hardest part.

Since this film was quite clearly staged, it allows for a greater control over compositions. One of Kubrick’s talents, here and throughout his career, was controlling light and shadow and heightening both; one of the reasons Kubrick made so many great black-and-white movies was that control. He learned that as a photographer (more on this next essay) and applied it here and in Fear and Desire. Almost every shot in Day of the Fight has that quality of dramatic lighting and spare composition, the kind that emphasizes the outlines of forms and turns almost everything we see into an icon. (The first act of Full Metal Jacket would accomplish the same thing in color.) Kubrick goes for balanced but not symmetrical compositions, keeping the left and right sides of the image active. The single images here are strong enough to carry a feeling of conflict and urgency without any narration; you can watch this film with the sound off and still be moved. The staging of the events makes this not something real that Kubrick captured, but something iconic that he made; something memorable beyond the bounds of its source.

Unlike the other two, this one has a good sense of structure. Having the action of the film lead up to a specific event means we can get interested and actively watch this; we’re not watching just to soak up information, but we’re thinking “what happens next? And when do we get to the fight?” That’s not a great or inventive structure, but it’s one that will easily get us through twelve minutes of film. A documentary, particularly newsreels like the first two or a propaganda work like The Seafarers, doesn’t need a story to work. It should have one, no question, but the interest comes from being a real piece of information, and that’s how these were seen. The newsreels are to give you something to think about before the feature starts; The Seafarers was there to list the benefits of SIU membership. In the early 1950s, these films didn’t need to draw a viewer in with story. Watching the documentaries, you get a clearer sense of what went wrong on the first two movies: he didn’t need to learn any kind of storytelling on the documentaries (Kubrick already had the story when he made Day of the Fight), and he wouldn’t have a good story until The Killing.

All three documentaries also rely on their voiceover, and so did Kubrick; the subjects of the documentaries rarely speak. The voiceover (and you really see this in The Flying Padre) binds otherwise disparate images together by literally telling what the camera is showing. With a voiceover, you can take any set of images and create continuity, and continuity was exactly what Fear and Desire was missing. Kubrick would use voiceover for his entire career; only 2001, The Shining, and Eyes Wide Shut don’t have one. Not only that, but most of the remaining films start with a voiceover, just as a documentary would, introducing setting, character, and action. This isn’t to say that Kubrick couldn’t do amazing things with voiceover (as in The Killing, Barry Lyndon, and Full Metal Jacket), just that it had an unquestioned presence in his films. And in the early films, it definitely substituted, poorly, for storytelling.

Previously: Killer’s Kiss (1955)

Next: Stanley Kubrick, photographer