Horror is a genre made for formalists. (Noel Murray)

Coming back to the The Shining reveals how many themes, actors, and even shots and sounds Kubrick lifted from his previous movies, and how much better they work here. Considering how far away Kubrick always was from naturalism, considering how much he always loved the human capacity to fuck up, it’s surprising that he never tried the horror genre before this, and not at all surprising that he hit it out of the park when he did. The Shining is many things, as decades of critical discourse and Room 237 will tell you, but first, last, and always it’s scary as all fuck.

Like action movies, horror movies work on a primal level, and because of that, they are probably the most universally appealing of all genres. That The Shining has entered popular culture and endured (“Heeeeeeeeeeere’s Johnny!” makes sense to zillions of people who’ve never heard of Johnny Carson or knew how Ed McMahon always opened The Tonight Show, and I just made myself sad) testifies to how well it works as a straight-up horror movie. Horror movies don’t work on the supernatural or psychology or even violence; all of those are means to an end. Like the dreams in Inception, horror works by reducing the situation to the most basic level: fear of the dark (The Blair Witch Project), of betrayal (Gaslight), of the body (the collected works of David Cronenberg). The Shining works because it’s about being trapped with an abusive husband and father. It’s about a family, something Kubrick has approached before (Lolita, Barry Lyndon) but never executed with the empathy that he and his cast create here.

How do you solve a problem like Jack Nicholson, or any movie star for that matter? They can’t disappear into their roles, they can’t be fully separated from their public personae. By 1980, the profane, funny, and pretty darn misogynist image of Nicholson was already in the public’s mind, and it closed off one version of The Shining: ordinary guy consumed by the demons of the Overlook. The solution to the problem–seen here and in Steven Soderbergh’s Solaris and PT Anderson’s Punch-Drunk Love and Nicholson’s great little cameo in Broadcast News–is that you don’t avoid the problem, you lean into the punch. You bring that public image into the movie and use it.

In the first scene, Kubrick and Nicholson show us a guy trying to contain the Jack Nicholson character within. Jack Torrance in the early scenes looks continually tense, on edge, formally polite over something deeply broken. (In his masterful Dissolve essay, Nathan Rabin describes him as a “’dry drunk,’ someone who has stopped drinking without changing the dysfunctional thinking and behavior of alcoholism.”) You can hear it in the drive to the Overlook in Jack’s line “he saw it on television”–the voice covers this wall of anger, and the eyes go full Nicholson for the first time. Look at the final picture of Jack in 1921: there’s the same strain on his face there too. The most important moment for the film comes late, when Delbert Grady (Philip Stone) tells Jack “you are the caretaker. You’ve always been the caretaker.” Jack is the madness of the Overlook, and it doesn’t defeat him so much as welcome him home.

Since Kubrick and Nicholson don’t start Jack as “ordinary guy,” they can’t end it with him merely going crazy. As The Shining progesses, Jack turns into something way beyond madness, something beyond even the 70s-trickster Nicholson performance. The bitter humor is there, but he uses his face and voice to go into wilder and wilder expressions and exaggerations. It gets funnier, but after Jack gets out of the food locker (which I always read as the one indisputable moment that shows the Overlook’s ghosts are real), he starts turning into a full monster. In the last minutes, limping through the maze with an ax, screaming, he starts losing everything human: reason, words, voice, motion. It’s like the death of HAL in that Kubrick and Nicholson show it as a progression, and he doesn’t find a grave, only a frozen forever in the Overlook.

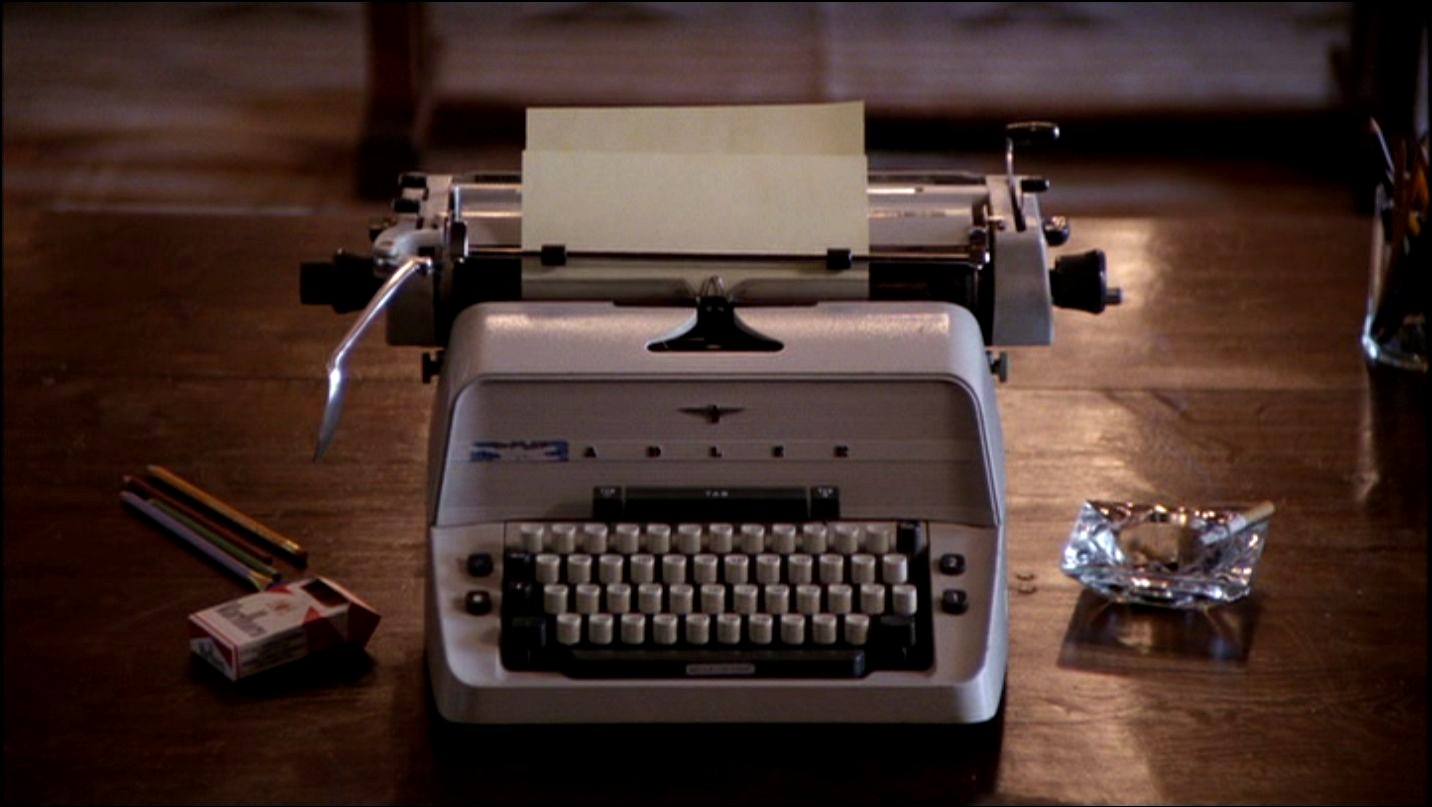

Joan Didion called The Shining “the first horror movie about writer’s block,” and that’s right for who Jack is. The Torrances’ apartment in Boulder has the exact graduate-student look to it (books everywhere but not in any kind of order) and Jack only talks about his “projects,” never novel, article, essay, or criticism; it’s the language of someone who thinks of himself as a Writer but doesn’t want to do any actual, y’know, writing. Jack’s response to Wendy’s “it’s just a matter of getting back into a routine” (“yep, that’s all it is”) is another moment where we can feel the rage, another moment when someone dares to give Jack any advice.

Jack desperately holds to a human façade, but not with his family; that’s why The Shining finds its real power not with Jack but with Wendy and Danny. In the first moment of interaction, Jack just dismisses Wendy with a “right” and never shows her a moment’s affection, and no attention unless it’s to insult her. As Wendy, Shelley Duvall gives one of my favorite performances in a Kubrick film or anywhere else. She’s playing a spouse who’s been beaten down (possibly physically) for so long she has gone into a survival mode, carefully watching herself at every moment, carefully limiting her expressions so as not to provoke Jack’s rage. (Kubrick never lets Wendy get too close physically to Jack.) Listen to the way she describes how Jack dislocated Danny’s shoulder; she sounds like a prisoner of war, and it’s so close to the way Jack describes it later that I’m sure it’s what he told her to say. She plays the escalating terror of the film so well, so that when she goes into the full screaming terror of someone snowbound with a crazy person, we’re ready for it. The great thing about Duvall’s work, and about Wendy as a character, though, is that she transforms. Through all the terror, she starts fighting back; she’s so much like Cathy Cahlin Ryan as Corrine Mackey in The Shield’s greatest scene, a heroine who through all her tears and screeching finds a way to claim herself and take control. (And it would have worked too if it hadn’t been for those meddling ghosts.) It’s one of the best performances of an abuse victim in movies, and it introduces a naturalism in Kubrick’s films that will come back in Full Metal Jacket.

The scene on the staircase shows both Duvall and Nicholson at their best, and it shows how simply and effectively Kubrick directs here. Nicholson is doing his Jack-thing, and there’s the scary/hilarious dialogue (co-screenwriter Diane Johnson is the underrated member of this creative team) for him; with its self-pity, self-importance, and full rage at a wife for daring to challenge him, it’s so close to Walt’s speech to Skyler in Breaking Bad‘s “Ozymandias.” What’s happening here isn’t comic relief but comic heightening, where the funny makes the scary more effective; I think it’s so effective because our reactions of laughter and fear keep interrupting each other without denying each other. Stephen King noted that a lot of horror only works because it borders on comedy; both horror and comedy are about the denial of the rational world, but horror keeps going away from it. On the stairs, the camera keeps pursuing both of them, literally step by step. What Duvall does with the bat is just amazing, because you can see her swings get progressively stronger–if she makes contact at the bottom, it’s nothing, but when she gets to the top, it’s completely believable that she takes Jack down. Characterization by swing, now that’s great acting.

As for Danny Lloyd, Kubrick continues his streak from Barry Lyndon of doing great work with child actors. Lloyd plays Danny completely naturalistically except when he’s talking to Tony; unlike almost any other Kubrick performance, he comes off as completely ordinary (even his haircut and clothes are exactly right for 1980), and because of that, completely moving. He seems like a real kid caught in the middle first of his parents fighting, and then a full-blown nightmare. When Danny talks to Tony, there’s a good move in his speech and the editing: when Jack and Wendy speak, the pauses between them are too long, so it doesn’t feel like conversation; when Danny and Tony speak, the pauses are too short. It gives an equal feeling of disconnection but for a different reason: Jack and Wendy are too far apart to communicate, Danny and Tony are too close.

Near the middle of the film, we get a powerful moment of Jack and Danny together, with Jack still in the bedroom, staring. The Nicholson-image is gone, and we just see Jack Torrance, alone and vulnerable for possibly the only time in the movie, and Kubrick shows us the simple beat of a father holding his son. It calls forward to There Will Be Blood, another movie about a father who loved his child but whose love got consumed by his demons (and that includes a specific Shining reference at the end). The way that Nicholson plays Jack so artificially makes this moment where he’s not doing that so powerful–and then he and Kubrick change the game, as the Jack-mask comes back and Bela Bartok’s Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta shifts. Next scene, the door to Room 237 comes open and the Overlook lets loose.

One final shout-out to the cast: I’m so happy to see Joe Turkel come back after so many years (his last Kubrick film was Paths of Glory), but I’m even happier to see Philip Stone, after small roles in A Clockwork Orange and Barry Lyndon, show up here as Grady. Like the entire film, his brief appearance slowly transforms from “well this is weird” to “dear Lord get me the fuck away from here.” That stare of his is just terrifying, as is his James Mason-level caressing and savoring of every word. Say it with me now: “corrected.”

Kubrick directs this movie with such precision, something necessary for how this movie works its effects. A Clockwork Orange demonstrated that Kubrick’s method doesn’t work with complete crazy; he does his best work where the crazy gets repressed or alloyed with reason. The Shining is one long slow burn, as Jack goes from abusive and vicious at the beginning to a dying animal at the end. Soderbergh remarked how contemporary movies have never been edited better on the microlevel and worse on the macrolevel; The Shining excels at both. On the macrolevel, as the movie progresses, the colors and music change, the images become more and more shocking, the events move farther away from reality, and the acting grows in intensity. The regularity of the camerawork (including the first major use of the Steadicam) plays against the jarring editing, creating a sense of control and of its loss–and the sense that anything could happen if that control is lost.

It’s that microlevel of editing where Kubrick does his best work in horror. Few directors use the dissolve or the cut as well as he did, using them to show that an entire world has changed. (Jay Cocks said that a reaction shot isn’t a cut to a reaction, it’s when the cut itself implies a reaction.) In his first scene, Halloran (Scatman Crothers) is so open and friendly with the Torrances and especially Danny, and perfectly blows off Wendy’s question “how did you know we call him Doc?” (Crothers also shifts his voice and approach depending on whether he’s talking to a black or a white person, which is well in character for a black man in 1980–or 2015.) Then the simple dissolve to Halloran alone in the frame with a completely new expression on his face tells us that there’s something hugely else going on. Kubrick edits sound and music so well here, too; it’s genuinely operatic, in that the progressively less tonal, more sound-mass-based music (discussed in this Soundtracking) feels like exactly what’s going on in Jack’s mind. There are several scenes where the music gets synced to the action at least twice in a single take, one more example of Kubrick’s precision, and how effective it is.

As an editor, Kubrick continually changes up his approaches, sometimes original, sometimes utterly conventional; we get a room full of cobwebbed skeletons for the sake of fuck. (Of course, that follows a shot of a guy in a bear/pig suit giving a blowjob, which shows how Kubrick and King mix up the approaches here.) We wind up in Wendy and Danny’s position watching this–we have no idea what’s coming next, we have no idea what might set the movie off. There are shock zooms and sudden cuts to (what may not be) hallucinations, like Grady’s murdered daughters; there are also shots held for so damn long so that we expect some kind of shock to come, and it never does. (Even the Overlook’s “impossible architecture” becomes part of this, as the madness extends beyond the editing of time to the orientation of physical space.) Twice, in the fireplace hall where Jack writes, Kubrick holds the camera at a distance and waits with us for Wendy to find out what’s going on; they’re two of the most unbearably suspenseful moments here. King, by the way, called one of those moments “a mistake a freshman director wouldn’t make” (thanks to Tasha Robinson for finding the reference); as the AV Club’s great Silver Age commenter danrimage said, this is why King must not be allowed within a thousand miles of any adaptation of his, ever. (For further evidence, watch this if you dare.) King may have bragged, however jokingly, that he outlived Kubrick, but this film will outlive them both. It will have a lot of meanings and interpretations, but it will always scare us.

Previously: Barry Lyndon (1975)

Next: Full Metal Jacket (1987)