In 1962, or in 2015 for that matter, if you’re making a film about a middle-aged man fucking a 12-year-old, you’re going to have to do it through suggestion and symbolism, so Kubrick makes suggestion and symbolism the real subject of Lolita. This isn’t a film about desire repressed, it’s about desire unspoken, hinted at, hidden, implied, rationalized, and romanticized; it’s about the way, as R. E. M. sez, “we have found a way to talk around the problem,” the way people don’t acknowledge what’s going on, even when they’re the ones doing it.

Before we ever get to Lolita (her age is never specified in the film, and Sue Lyon looks and acts around 14) and Humbert Humbert (James Mason) alone with each other in a motel room, there’s innuendo everywhere: Humbert’s landlady and Lolita’s mom Charlotte Haze (Shelley Winters) making a play for Humbert from the moment she meets him, a wife suggesting an open marriage at a high school dance. There’s also the sense of the ever-present society of American suburbia, always there in your life but never saying exactly why; Humbert can’t even get quietly drunk in a bath without the neighbors showing up. We get, like in A Clockwork Orange, the sense of a society that’s always there to interfere with desire, and the sense that might be something really necessary.

The film itself gets in on the act, with details all through it that are so obvious in their symbolism that it’s funny, like the Coen Bros.’ accuracy. Humbert gets left with a half a hot dog, characters have the names Mr. Swine and Dr. Cuddler, Lolita reads The Frigid Queen, she goes to Camp Climax for the summer, a gun on one nightstand and a picture of Lolita on the other. No wonder Kubrick and Nabokov hang a lantern on all of this with a character saying “I wondered if the symbolism wasn’t a bit heavy-handed at times.” This strategy is never more effective than in the crucial cut to black on Lolita and Humbert in the motel room–because Kubrick and Nabokov have demonstrated how much happens that will not be spoken, when she leans back and says “alrighty then,” there’s no doubt about what happens next. . .because of the implication. (Well, given that there are people who think Adriana LaCerva is still alive, someone probably can doubt it.)

Kubrick has been criticized for abandoning Vladimir Nabokov’s extraordinary prose, but that’s an effective part of his strategy. Nabokov writes the story from inside, and Humbert Humbert ranks at the top of the Unreliable Narrator All-Stars. Kubrick, effectively for a movie, works both within and without Humbert’s perspective. (Another thing I like about this version: Lolita gets out alive at the end.) We get just enough of Humbert’s journal and voiceover to know how he sees himself, as an Old World Romantic figure among uncultured Americans, and Lolita is the one he’s going to initiate into his world. He also continually refers to himself in the third person, heightening the sense of self-deception, making himself into his own literary character. We also get some neat criticism of Humbert’s self-deceiving language in the first scene, as Clare Quilty (Peter Sellers) reads Humbert’s poem and dismisses it (“gettin’ kinda repetitious”) in a full cowboy accent.

This is the first time that Kubrick has really used voiceover effectively. It’s not giving us information we should already have, or do already have, or don’t need. It plays up the difference between what Humbert thinks and what he’s doing. Kubrick’s sense of Humbert’s autosuggestion extends through language to the look and sound of the film: even the soft focus he uses on Lyon as Lolita does that, because there’s a moment in the film when he stops using it, showing the first hint of Lolita becoming her own person. He does it at the moment when Humbert reveals that her mother has died, as subtle and effective as the shift from black-and-white to color in Memento. As discussed in last week’s podcast, Spartacus feels like it pushed Kubrick to use music differently than before. The music in Lolita, courtesy of big-band leader Nelson Riddle, has less of a presence than in Spartacus but it’s just as big when it’s there. What makes it different is the way Kubrick deploys it; when Lolita leaves for summer camp, the music goes hugely, sweepingly romantic. It’s like the soft focus, putting us musically in Humbert’s mind. At the end of the film, when he sees Lolita with a working-class husband in a working-class home, the music is pure horror score. In musical terms, the score plays in contrary motion to the images and the performances.

That use of the soundtrack as the music playing in the protagonist’s mind calls up The Shining, played in the key of naturalism rather than horror. Certainly the first half of the movie has some of The Shining’s situation, man, woman, and child stuck in a house together with all sorts of undercurrents and things not said going on. Visually, too, there’s a staircase shot here that will be repeated in The Shining, and a shot down a hospital corridor late in this film that will be one of the latter film’s defining visual motifs. Seen against his entire career, one of the things that Lolita gains is the sense that Humbert isn’t all that different from Jack Torrance.

Even more than Kubrick’s direction, Lolita rests on James Mason’s performance as Humbert, continuing the streak of great aristocratic characters in these films from General Mireau to Crassus to here. Appropriately for an aristocrat adrift in 1962 suburban America, the dominant note of Mason’s performance is discomfort; he looks like the oxygen in the air bothers him. Mason’s line readings are of course legendary; he doesn’t just chew his dialogue, he sniffs it, samples it, runs it around his mouth and appreciates it before swallowing, again exactly right for a professor of French poetry. (Anthony Hopkins’ Hannibal Lecter and Gary Oldman’s Dracula both owe something to Mason’s performance here, and James Purefoy’s Joe Carroll in The Following was its non-union Mexican equivalent.) Humbert only appreciates those whose language is up to his self-deluding level, so it’s symbolically right that his greatest challenges in the film are all from American popular culture–bubble gum, school plays, and his nemesis Quility is a television playwright. He goes beyond George Macready’s Mireau; Humbert isn’t just above his surroundings, he’s made mildly ill by them. When he plays scenes with Shelley Winters, he’s acts like it would be beneath him to show her any kindness.

In his scenes with Lolita, he hits the notes of lover and father, both of whom are incredibly possessive (I always hear Depeche Mode’s “A Question of Time” as being sung by Humbert); Kubrick, Nabokov, and Mason fairly mercilessly expose Humbert’s need for control. There’s a powerful, Kubrickian moment where his rage brings the books in the back of the shot crashing down, as his need for order creates more disorder. Revisiting this in 2015, the most disturbing thing about this is watching a man who thinks that because he provides everything for someone, that he owns her. Humbert’s continual rage and jealousy towards Lolita, his ever-changing rules for her, his refusal to let her grow, and most of all the way he sees all of this as love, make this film 50 Shades of Grey with Christian Grey as the protagonist. That makes the 50 Shades trilogy a contemporary retelling of Lolita, except Lolita stays with Humbert forever–and E. L. James thinks that’s a happy ending.

Shelley Winters has the toughest role here and brings it off, managing to be funny and pathetic and never not sympathetic. Charlotte throws herself at Humbert from her first moment onscreen, and Winters makes it nearly literal; all the major performances here are full-bodied. The themes of indirection and language play out with her. Charlotte has never been in a position to talk about her feelings, or directly ask for what she wants, and Winters plays a woman whose desperation comes from that. Kubrick also has an advantage here than Nabokov denied himself: he can give us scenes of Charlotte alone, breaking down and crying after yet another brush-off from Humbert, and Winters is just open and heartbreaking there. She can also wear the shit out of a leopard-print dress; when she shows up the next morning with an apron over it, it’s one of the best visual jokes in a movie full of them.

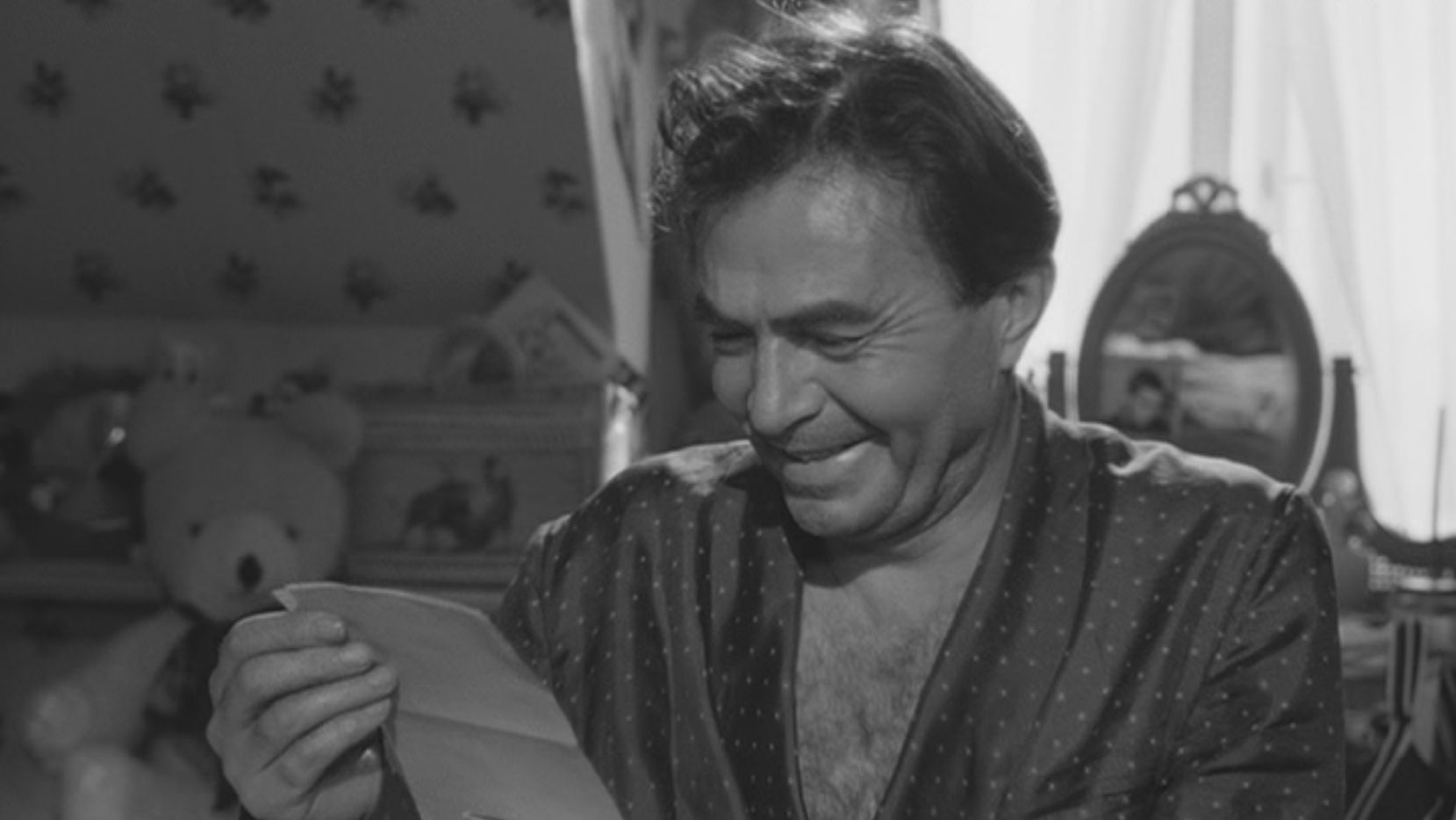

The scene that’s stayed most in my memory collides Mason’s performance with the memory of Winters’: Humbert reads Charlotte’s passionate, clumsy declaration of love, maybe the only time in the whole film a character flat-out tells someone what she’s feeling, and he absolutely pisses himself laughing, mocking her words with his voice. (Neat touch: this is in Lolita’s bedroom, and Kubrick pans to a picture of Quilty at the end.) Humbert always treats Charlotte so cruelly–he rarely even looks at her when they’re together–but Mason goes next-level vicious here. It’s one of the great moments of dark, dark comedy in a Kubrick film, right there with the unconscious Joe Turkel in front of the firing squad in Paths of Glory.

Digressing briefly: After five minutes of watching Adrian Lyne’s 1997 version, I knew that no matter what they’d show, they would never have the guts to do this scene, and I was right. The absence of that scene crystallizes what Lyne wouldn’t do in filming Lolita. He wouldn’t dare to make it funny. Unlike Kubrick, Lyne includes the detail of Humbert’s lover dying when he was a teenager, and that sets the tone for his version, systematically drained of all comedy. That especially comes through in Jeremy Irons’ performance as Humbert, which is an insane decision–he already gave a full, hilarious, disturbing, Masonic performance as Klaus von Bulow in Reversal of Fortune. (For that matter, there’s more humor in Irons’ Scar in The Lion King than in his Humbert.) The lack of comedy and Irons’ I-am-so-sad-I-am-so-very-very-sad performance reduce Humbert from a character to a case study; all the way through, Lyne’s Lolita is both more explicit and less believable than Kubrick’s version.

Back to 1962: Lolita feels looser and more episodic than any other Kubrick film. For the second half, when it’s just Humbert and Lolita, it’s really a road movie, and no other film of his has so many establishing exterior shots. Ten years after On the Road, Kubrick and Nabokov get at something dark about the American journey, about “lighting out for the territory”: it always means destroying your past, it’s about never having a home anywhere. For Humbert, it’s one more form of self-deception, staying out of range of the law and more importantly, forever out of range of your own conscience.

Peter Sellers’ Quilty functions as that conscience, and it’s a work of genius, as a character and as a performance. Quilty emerges from under a sheet (the last scene of the narrative and the first scene of the movie) with the line “No, I’m Spartacus,” which I read as a fuck-you to the entire previous production. That also sets the tone for everything Sellers does. The way he always just shows up (and the way Kubrick shoots and frames him) wherever Humbert and Lolita are make us wonder how real he is–like the events of Eyes Wide Shut, his position in reality isn’t either-or, it’s how much. At times Lolita feels a John Cheever work, particularly The Swimmer, what might be called American Suburban Magic Realism.

Kubrick started his career with Paul Mazursky doing a bad imitation of madness in Fear and Desire, and there have been little hints of crazy in his films since then, but Sellers is the real thing, improvising, impersonating, completely unique in his voice, language, appearance, and motion. (Quilty dancing is the funniest and spookiest thing you’ll see that side of Twin Peaks’ Little Man in a Dream.) Kubrick can’t assimilate this being into an ordered universe, and he doesn’t try to, because Quilty is the greatest disorder in the world Humbert’s trying to make for himself and Lolita. He’s the id playing the role of the superego, the judgment of society from someone who might not be from our reality, let alone our society, and he’s even more fun than that sounds.

Coming back to this film from a few decades away, I was surprised by how much I liked it, and how little it feels like Kubrick’s other films. The themes of some of his other works are there–the conflict between self and society of A Clockwork Orange, the dark comedy of Strangelove, the family dynamics of The Shining, the psychoreality of Eyes Wide Shut–but they’re played in a more naturalistic style than in any other Kubrick film. After this, Kubrick would be much more dominating in shaping his adaptations, and he would use a much more stylized approach to the themes here. There’s something of the feeling here of John Ford’s or Sidney Lumet’s films, of a distinctive artist working to make the material succeed on its terms, not his own. It’s not all that Kubrickian a film, and it’s a very good one.

Previously: Soundtracking #8: Spartacus and the early films

Next: Dr. Strangelove (1964)