Crime does pay, just not very well. (Matchstick Men)

Barry Lyndon feels like one of the few works that Kubrick adapted rather than used as a scaffolding to build his own work upon (has anyone checked with Stephen King to see how he felt about The Shining? Seems to me like Kubrick took a few liberties with the source material) but it also feels like Thackeray was one of the few authors he wanted to–that he could–adapt with any fidelity. It’s Kubrick’s No Country for Old Men, one artist adapting the work of another with a similar but not identical worldview.

Like No Country, it’s a true adaptation, not a transcription (looking with a Leonard Rossiter-style “epic sneer” in your direction, Revolutionary Road); Kubrick uses a couple of daring cinematic strategies here, both of which play into his strengths–really, his mannerisms–as a director. First, he plays up the static, visual aspect of film. Many shots look like portraits and landscapes, and Kubrick holds on them for even longer than he held shots in 2001. So many shots evoke specific paintings of the period, but Kubrick goes well beyond that, beyond appearance into world-building. Barry Lyndon feels like he took the paintings, music, and literature of the period and asked “what world is implied by these artifacts?” The clichéd critical line would be that it’s a set of paintings come to life, but Kubrick reverses that: Barry Lyndon is life lived as a series of paintings. This method comes off at first as unhistorical, but stop for a moment and consider how that word usually gets used. Most of us learn history as a series of large events, and historical fiction connects its characters to those events. It’s why we tend to see history as Great Men Doing Great Deeds; it’s a view of history largely influenced by epic poetry. Kubrick, however, uses an aesthetic model of history here, where the music and images of a period lead us to its historical truth. It’s a different, tricky, but no less valid way of approaching history; it trades what can be documented for what can be felt.

To some extent, this is also the method of Mad Men, but the contemporary film that most resembles Barry Lyndon is Sofia Coppola’s underrated Marie Antoinette. Both Lyndon and Marie end in 1789, with the sense that this kind of world has come to its end. Another favorite historical film with a different approach than these two (and the same sense of the passing of a world in the ending), The Last of the Mohicans, overlaps with the first part of Barry Lyndon, taking place in the American rather than the European theater of the Seven Years’ War. It’s a kick to think that Michael Mann’s, Kubrick’s, and Coppola’s characters all share the same universe.

The first thing to note about the painterly style is its utter, breathtaking (literally) beauty, moving the characters from one perfectly composed image to another. Kubrick can even find one-point perspective in a goddamn forest, that’s how much control he has over images. (As Jason Mantzoukas sez, watch this film and try not to come.) At times, Barry Lyndon gives the same feel as a Kurosawa or a Malick film, as if the weather gets wrangled according to Kubrick’s wishes. (I don’t think there’s a single clear sky in the whole film.) Famously, he shot this film using only natural light, and that required the development of special lenses for the indoor shots; for those of you fascinated by Kubrick and technology, note that he developed the future to create the past. Those indoor, candlelit scenes have a warmth to them that’s unlike any other movie. In other films with candles, they form distinct, bright points of light in the composition; here, Kubrick captures the warm, yellow-orange glow that pervades a room lit by candles. It’s intimate, romantic, and also cramped; on a movie screen it’s even more effective, because it’s surrounded by darkness. One of Kubrick’s signature camera moves–the slow zoom-out–becomes more effective because of this style; he often starts a scene with by zooming out from a perfectly composed, static image, and it has the feel of a chapter heading. (On which more shortly.) The period details can also be incredibly funny, as when Barry launches a brawl in an elegant salon and bodies go flying everywhere, because you try getting any traction on those floors with those shoes.

In addition to period visuals, Kubrick employs period music, orchestrated and arranged expertly by Leonard Rosenmann. In addition to Classical music and Irish airs, he uses Handel’s Sarabande as a simple, effective repeated motif. Like a lot of Baroque music, the Sarabande has a clear progression and a straightforward melody, and that allows Rosenmann to orchestrate it in a lot of ways. It can feel epic (as it does here in the title), romantic, or ominous depending on how it’s played.

Audio PlayerThe style defines the performances. Here, Kubrick’s experience and methods as a photographer pay off, because he’s very much building the characters from their appearance and how they’re lit and positioned in the frame. It makes sense for the period and the story, built so much on assumed identities, costumes, and masks. Patrick Magee, with a wig, powdered face, eyepatch, and beauty mark, does so much better here than in A Clockwork Orange as Barry’s mentor and partner in crime. He’s warm, friendly, funny, and all mask; Barry will at one point mask himself as Magee. As Lady Lyndon, Marisa Berenson doesn’t do much more than look sad, but she kills it on that point, and the story and the voiceover make it hurt because it’s clear she has no other function in his life. Even her wigs start to look tired as the story moves on. Berenson was a model, a profession with its own set of skillz and discipline, and Kubrick chose her on the basis of her wide-eyed look. She does seem to have stepped out of a painting of the period, and he lets her step back in.

Had this movie been made now, Matt Damon would be a lock to play Barry; Damon does so well with characters who are liars and hide it behind a wholesome, farmboy façade. (Barry’s very much an 18th-century Tom Ripley, a social climber without much conscience to get in the way.) Here, Ryan O’Neal doesn’t look like anything but Ryan O’Neal; he’s not an actor of great range or expression, and he’s not entirely convincing at the beginning. His performance, though, gets better as the movie goes on; the dominant feel of his performance is that he’s out of place, which makes more sense the farther he gets from his own society. He also has less and less to say, so that by the end, just a shot of him saying “yes” becomes sad and very scary. He’s also assisted by having so much of what he’s feeling narrated, which, like Berenson, relieves O’Neal of the need to portray those feelings; in fact it makes it necessary that he doesn’t portray it. Kubrick turns a limitation into an asset here.

Kubrick’s second strategy is his use of that voiceover, used since Day of the Fight, but never as unusually and effectively here. Like the visual style, the narration is straight outta the 18th century. Perfectly delivered by Michael Hordern, it’s sardonic, bemused, omniscient (unlike the novel itself, which is in the first person); it’s that classic narrator that already knows the whole story and will tell us in good time. In its most arresting aspect, the narration often runs ahead of events, so we hear about things before we see them. (We’re clued in to that in the very first scene.) The word “irony” gets thrown around a lot, but this is one of the strongest examples of it, where we know just how ineffective or just plain stupid the characters’ actions are. We know that not because of the language or the tone of voice, but because we know what’s going to happen. Back with the documentaries, I noted how voiceover can give a sense of unity to images that are without their own narrative; here the voiceover both weaves in and out and around that narrative, making the images and narrative something more than they would be without it.

Narrating exactly what happens weakens a movie, but the narration here adds flavors of humor and regret to the overall stew of ownage that is Barry Lyndon. At the end of Part One, for example, the narrator reads a newspaper account of the death of the first Lord Lyndon while we watch him having a heart attack. The narration doesn’t make the movie boring because it’s clear the narrator isn’t going to reveal everything; there’s a crucial detail about Barry’s first duel that we don’t hear until much later, and not from the narrator. Again, the narrator becomes another consciousness in the movie, and his perspective becomes clearer and more interesting as the story progresses. Another great example comes when Barry oh-so-tenderly seduces a German woman whose husband is away at war, and equally tenderly leaves her in the morning. The farewell gets some beautiful music, beautiful visuals, and a voiceover revealing “a lady who sets her heart on a lad in uniform must be prepared to change lovers pretty quickly or her life will be but a sad one. This heart was like many a neighboring town and had been stormed and occupied several times before Barry came to invest it.” The voiceover makes it a great joke on Barry, turning the protagonist of this story into a minor, interchangeable character in someone else’s. I’m sure in Thackeray’s time she was considered a faithless whore, but I could only think of her as Amy Schumer in the Seven Years’ War, catching a dick whenever she wants. You go, girlfriend.

Smart as it is, Barry Lyndon is way more than an intellectual exercise, and much of that is down to Thackeray’s writing. He was quite possibly the greatest writer ever about social climbing, having the advantage of living through the breakdown of static, enduring social classes and witnessing the rise of, well, people who could rise. Thackeray knows how to make great stories and memorable characters out of that. Barry schemes, lies, masquerades, duels, fights, marries, anything to get ahead, all of which is entertaining and wickedly funny; Part One (“How Redmond Barry Acquired the Style and Title of Barry Lyndon”) is the funniest ninety minutes in all Kubrick that’s not Dr. Strangelove. (The two lethal but extremely polite highwaymen are a favorite example.) Running alongside the humor is Thackeray’s so very noirish sense of how people get destroyed by themselves and by fate: Barry’s single act of mercy directly causes his downfall, because of course that’s what would happen.

Thackeray and Kubrick also merge their sensibilities on the duels of the film. (The three duels appear in the same places–the first thing in the film, a little later, and just before the end–in Barry Lyndon as Thus Spake Zarathustra appears in 2001, which probably isn’t relevant but is nevertheless cool.) They also give Kubrick a chance to show his love of process, following the seconding, the loading of the guns (a crucial detail for the second duel), the pacing, the commands, the shooting (English and Irish duels seem to follow slightly different rules), and the question of honor. It’s also one more iteration of Kubrick’s reason-as-madness theme, because as Dave Nelson sez, “that is the procedure and the procedure must be followed!” and if your gun goes off by accident, tough shit. It’s a crazy thing that everyone accepts in the world of Thackeray.

Money is another. The second half of the film is largely about money, another subject Thackeray was so good at writing. He and Kubrick play this with bracing unsentimentality: the narrative largely runs on characters trying to get money or hold on to it. In the first half, the Barrys effectively exile Redmond to secure a fortune; in the second, there’s a repeated scene of Lady Lyndon simply signing checks, and that’s in fact how the film ends. Kubrick never glamorizes it, explains it, or connects it to anything else; George Orwell said that in Thackeray “the desire for expensive clothes, gilded carriages, and hordes of liveried servants is assumed to be a natural instinct, like desire for food and drink” and that’s what we see here. It’s fascinating, and disturbing, the way money gets connected in our world to all sorts of moral virtue; to see it simply accepted here as natural law is one more way Kubrick shows this is a different world.

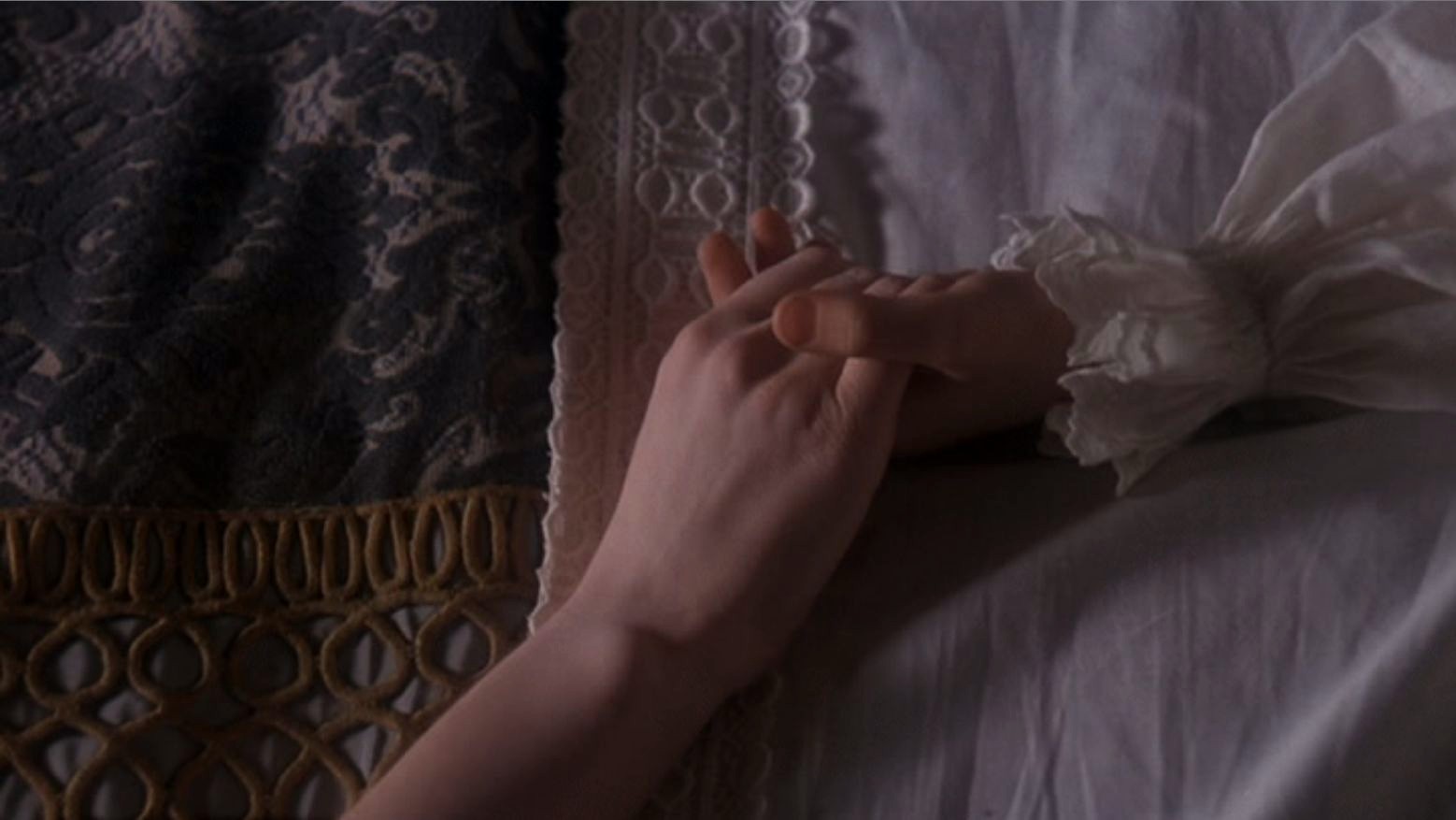

Kubrick hits sentiment in only one area here, the love of parents for their children, both in Mrs. Barry’s love for Redmond and Lady and Barry Lyndon’s love for their son, Brian. This could so easily go into gooey, manipulative sentimentality, but Barry Lyndon misses that and lands on something genuinely moving. With Mrs. Barry, it’s because she’s just as much of a dealer as her son; she’s completely ruthless in protecting him (once he’s secured the Lyndon fortune, that is); with Brian, it’s because Kubrick keeps to his visual strategy and lets the faces and images do the work. Berenson’s grieving face, without wig or obvious makeup, just devastates, as does the single, Fearless-like shot of Lady Lyndon and Brian holding hands. Making a movie that’s so low-temperature and deliberate makes moments like these have real impact. (The love of mothers for their children will come back in Kubrick’s next film, of course, as will his ability to direct child actors.)

Most historical movies suffer from one of two failures: either they tell a modern story with period details (and Spartacus often has this problem) or they get so caught up with historical accuracy that the characters don’t come to life. Barry Lyndon avoids both failures, creating a living, distinct world from a time’s art and culture rather than its historical events. (L. A. Confidential makes for another good point of comparison.) It’s easily Kubrick’s best historical movie (and one of the best historical movies, period), and probably his best adaptation.

Previously: A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Next: The Shining (1980)