Everything Stanley Kubrick learned went into the making of 2001, and he made something utterly unlike anything he or anyone else had done before. You can see elements here that go all the way back to his skills as a photographer; you can see his understanding of how we perceive space and time in film, and how he manipulates them. His fascination with and understanding of human behavior extended here to the whole of humanity, and to one of the most memorable non-human characters in fiction. His need for collaboration brought in one of his most complementary and best co-authors. All these elements have never been so present, and so necessary, to create one of the most moving films I’ve ever seen.

Earth

“The Dawn of Man” is a Kubrick picture story come to life, movement, and sound. It’s slow and yet never dull, because each image conveys information or motion; the first shots show the day beginning, already imparting both a sense of forward time and an introduction to a world. (The opening of No Country for Old Men is almost identical to this, except set in the American Southwest.) Once we see the primates, we move from establishing a landscape to establishing the community–what they eat, how they eat, how they live and sleep, and how weak and vulnerable they are–each moment marked off by slow fades to black.

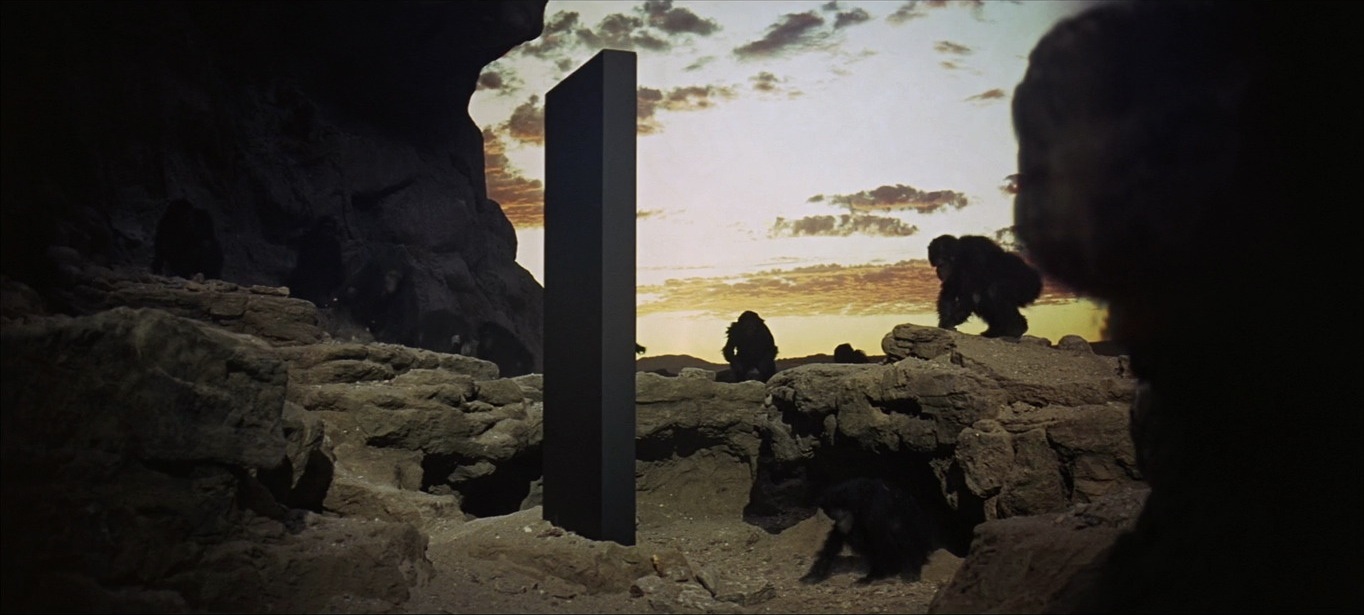

Then the monolith appears, accompanied by György Ligeti’s Requiem, perhaps the most iconic and mythic image Kubrick ever invented. (It went through a lot of stages to get to the giant black slab, about which more next week.) It’s out of place in every way–in the sound, in the color, in its geometry; somehow it’s the verticality that’s most disturbing. Kubrick exactly choreographs the primates moving around it into a position of supplication or worship.

I’ve never gotten the charge of Kubrick being “unemotional” or “anti-human,” largely because of what happens next. Without any words, with the most essential resources of cinema–the low shot of the monolith (as if it’s gazing down), editing, varying film speed and perspective, and most of all the use of Richard Strauss’ Thus Spoke Zarathustra–he shows us the beginning of humanity. This is it. This is how it happened: something alien showed or presided over the first primate to use a tool, and everything else followed. We learned to have dominion over the beasts of the earth, we learned how to eat, and we learned how to whale the living shit out of others. Our mastery, our health, our knowledge, and our war all come back to this moment. Kubrick and co-writer Arthur C. Clarke do nothing less than create their own origin myth here, their own Genesis. I cannot watch this sequence without tears, and without pride.

The Moon

The first part finishes with another famous, simple, and cinematic moment: the cut from the bone club to the satellite in space, implying that the next few million years or so were nothing new, just playing out the consequences of that first moment. If you reflect on it, you can see the funny in the compression of the human story:

1) Four million years ago, primates began using tools.

2) Four million years ago — 2001, they got better at it.

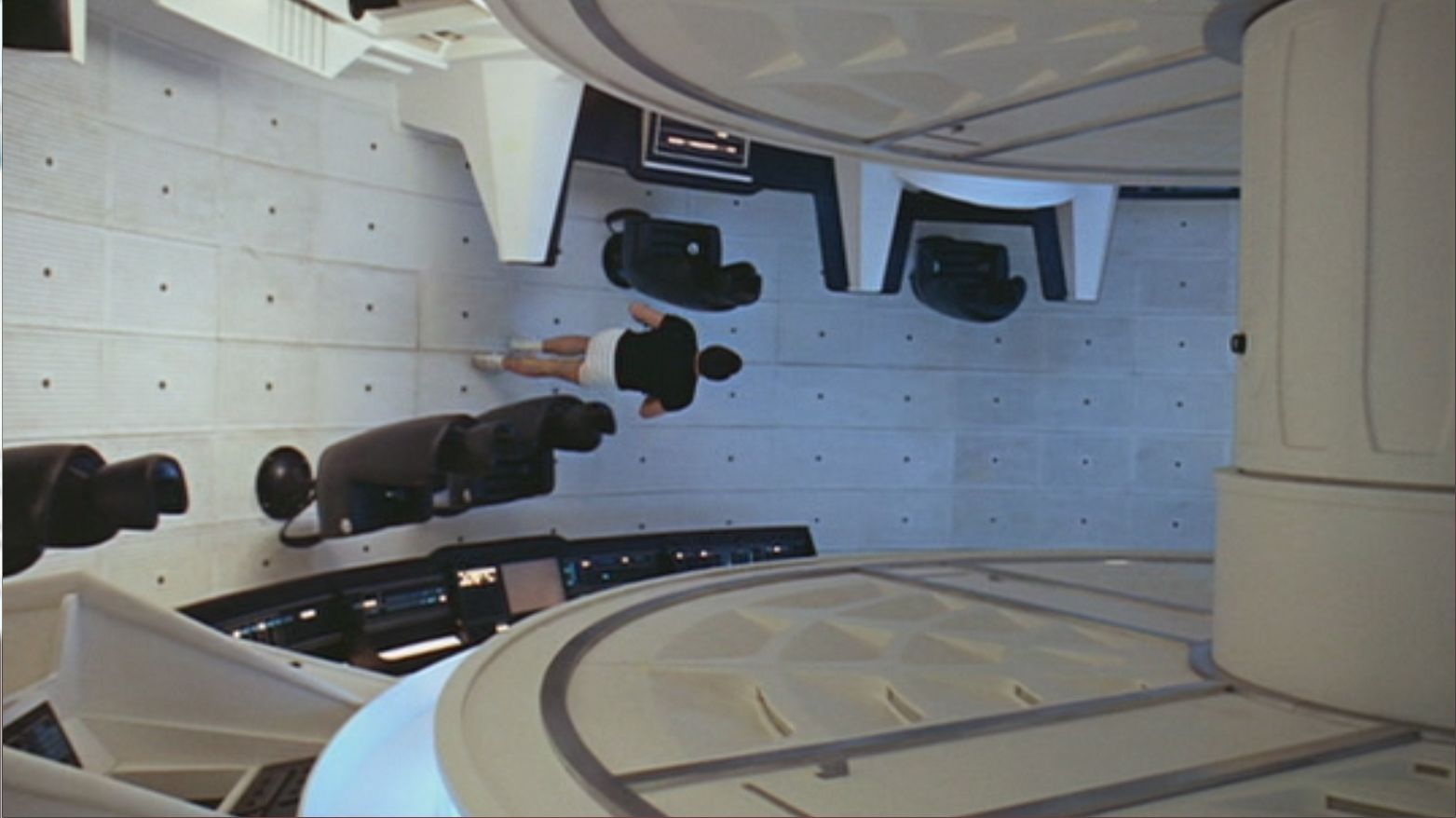

Kubrick does something nearly unique in the space sequences here; I can’t think of any other movie except Alfonso Cuaron’s Gravity that does it. (Orson Scott Card described this kind of perspective in Ender’s Game, and made it a crucial part of the plot, but I’ve never seen the film.) Most films set in space film events as though they were flying sequences, with a clear indication of up and down, and a ground plane that’s under everything. Kubrick does more than abandon the ground-plane perspective; really, he abandons the entire Cartesian perspective of three perpendicular dimensions. In 2001, spaceships approach, as they would, along diagonals and curves and Kubrick keeps our point of observation neither above nor below, but simply at a distance; he moves the camera through curves that have no analogy on a world with gravity. (In an upcoming Soundtracking, I’ll discuss the role of music in these sequences too.)

The precision and geometry of Kubrick’s camera has never been so necessary as in this film. He locks it in a fixed position as the set turns, allowing characters to walk in vertical circles, go upside down, sideways, to see the carousel of the Discovery spaceship motionless from the side, an original and wildly disorienting use of widescreen. In some of the extreme long shots, you can see people oriented both normally and upside down. So directly, we see space, and travel through space, as something fundamentally, geometrically different from everything we’ve known.

Well, maybe not all that different–in space and on the moon, Kubrick keeps a fun undercurrent of everyday life going on. It’s there in the brand names and logos that we keep seeing, not all of which made it to 2001: Pan Am, Hilton (you just know Conrad Hilton called up Don Draper when 2001 was released and said “now that’s what I’m talking about”), Howard Johnson’s, the Bell System, BBC. It’s there in the ham sandwiches that have gotten pretty good, suggesting that not all technology moves at the same pace. All of this is still and forever true; 2001 has anachronisms but it’s never become dated. My favorite of all of these is Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) burning his fingers on the food tray; there’s a bit of “every damn time!” in his gesture, like Discovery has always had this problem. It’s one of the many ways in which Kubrick makes this story about people, not just humanity.

“I’m afraid, Dave.”

Like the opening sequence, the storytelling on board Discovery is both spacious and stripped down, with Kubrick explaining so little. The visuals are stripped down, too; Kubrick began his career with light against dark, a world made in high-contrast still images, and he does the same thing here. We keep seeing the bright lights of the pods against the blackness of space, the stark, geometric whites and blacks of the ship, even Bowman’s pen-and-ink drawings. There’s a good design touch here in that every surface, interior and exterior, seems just cluttered enough, not the saturate-all-the-visible-area-with-blinking-colored-lights approach of so much science fiction. You get the feeling that these ships can be used by people. And hey, Bowman and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood) have some pretty cool (if oversized) tablets there. The one spot of color is the red eye of HAL 9000.

The least appreciated artists of 2001 are Dullea, Lockwood, and William Sylvester (who plays Heywood Floyd). Critics have often written off these performances (Foster Hirsch described them as “three exemplary men of the future, competent, well-adjusted to their environment, betray[ing] no feelings whatsoever. Their cool exteriors are not masks–are, in fact, all that there is to them.”) but they’re so necessary, and so good. Bowman, Poole, and Floyd are stone professionals, straight out of a Michael Mann film. Sylvester’s moment on the space station when he fakes Leonard Rossiter into perpetuating a false rumor by denying it shows his skillz are on the level of any of Mann’s characters. They are not without emotion; they have a job, and they’re in an environment, where emotions simply don’t count. They give the smallest emotional beat the greatest weight; watch Bowman as he retrieves Poole’s body, and sees him. We don’t see Poole, we only see Bowman, and he can only allow himself a single moment of grief; there’s just no time for anything else. It’s heart-rending, and a few minutes later, Dullea follows it up with a moment of pure comedy, an honest-to-God triple take when HAL reveals he knew Bowman was planning to kill him. (It’s just short of homina-homina-homina.) And that gets followed with another great, suspenseful sequence as we watch Dullea, step by step, prepare to blow himself out of the pod and into the ship, as detailed as Mann tracking James Caan breaking into a safe in Thief. Like so many Kubrick performances, it’s thoroughly human, just not what we’re used to seeing in films.

HAL refusing to let Bowman back on board leads one question of many that never gets resolved: what happens to HAL that makes him kill off the crew? Clarke gives an answer in the novel (it’s the best two pages he ever wrote): HAL went mad, almost literally schizoid, from having to keep the purpose of the mission secret from Bowman and Poole. We’re told, in the last lines of the film, that HAL was keeping that secret, but that’s the only clue Kubrick gives here.

My reading this time through isn’t completely different, in that HAL lost himself over something he couldn’t comprehend. I think HAL had never made a mistake; we’re told that no HAL 9000 computer had ever made one. He made a mistake in predicting the antenna fault, and had no way to understand that. HAL’s tragic flaw was his infallibility–if he makes a mistake then he isn’t HAL anymore. Like so many tragic characters, the flaw led to paranoia: once he knew Bowman and Poole were planning to disconnect (i.e. murder) him, his next step became necessary.

If there’s any doubt that HAL is a full character, the editing clears that up. Fear and Desire was completely silly in how it reused shots, but 2001 does so much with the single, repeated close-up on HAL’s eye that it’s effectively a visual essay on the Kuleshov Effect. (He did a series of experiments in the 1920s, showing how audiences would interpret the same shot differently depending on what shots preceded and followed it.) The identical shot can make HAL appear confident, smug, hurt, enraged, amused, or murderous depending on its context, and how Dullea and Lockwood act.

HAL’s emotions are, in part, down to Kubrick’s skill in editing; the rest comes in Douglas Rain’s astonishing vocal performance, never more so than in HAL’s last moments. After over 40 years of watching movies, this is still the death that lands the hardest. It’s prolonged, methodical, like Kubrick and Rain are exploring exactly what happens in the instant of dying, what it will feel like for each of us. We can hear, moment by moment, a consciousness (can we call it a soul?) disappearing, and with no sense of it departing for the Great Perhaps. “My mind is going,” HAL says, but it’s not going to anyplace. Rain’s voice has played a range of emotions, so subtly, all through the film; he’s an absolute Bond villain when he locks Bowman out of the ship. (“You’re going to find that rather difficult without your space helmet.”) Here, for the first and last time, there’s anguish; as best as he can, he’s begging for his life; the hitch in “I’m a, fraid, Dave” terrifies, both with the words, the feeling in them, and the mechanical break. Near the end, as the oldest memories start coming to the surface, the voice changes again, becoming brighter, younger really, and that’s so much worse, he can’t even beg anymore. And then the last, horrible mechanical slowing down of the voice to nothing–not even death anymore. He’s just off.

“Upon his own land, Odysseus awoke; and knew it not, for he had been long away.”

The “And Beyond the Infinite” sequence shows Kubrick’s skill in not just creating a spectacle (and it’s surely the most spectacular sequence in all his films), but in having it mean something. Again, he manipulates the ground plane or its absence to orient or disorient us. At the beginning of the sequence, the colors come at us vertically, which has no analogy to anything we could see or experience, unless it’s a Huxleyian door of perception opening. (A very 1968 idea, that.) Then Kubrick moves to a more space-disoriented perspective, with things appearing above, below, and to the side of our vantage point. There’s some distinct sperm and embryo imagery there, too, and sometimes I imagine the seven crystalline structures as sentinels watching over the journey. (More next week about sentinels, too.) Towards the end of the sequence, Kubrick reasserts the ground plane, bringing some of our orientation back and creating the sense of coming in for a landing; some of the images are from the flying sequences in Strangelove, falsely colored. There’s also a careful manipulation of ambient sound and music all through the sequence. It dazzles, but it’s also a journey, and we can feel that.

In the cuts back to Bowman, Kubrick also shows how the flow of time changes. We start with the held shot of Bowman’s head shaking, then go to jarring pictures (not shots) of him screaming, then to single shots of his eye in false color. All this tells us time isn’t working the way we’re used to, and sets up what will happen in the room, as Bowman sees himself age and transform in a series of jump cuts. (Kubrick also signals each transformation with sound–we hear the next Bowman before he sees himself.) Like so much of 2001, what’s going on is mysterious, but the presentation follows a strict rule, and that sense of an underlying but ununderstood order does so much to create the feel of an alien consciousness. And I’m also happy to see, after all the ripped chunks of flesh, liquid meals, and unidentifiable colored stuff, someone finally gets a proper dinner.

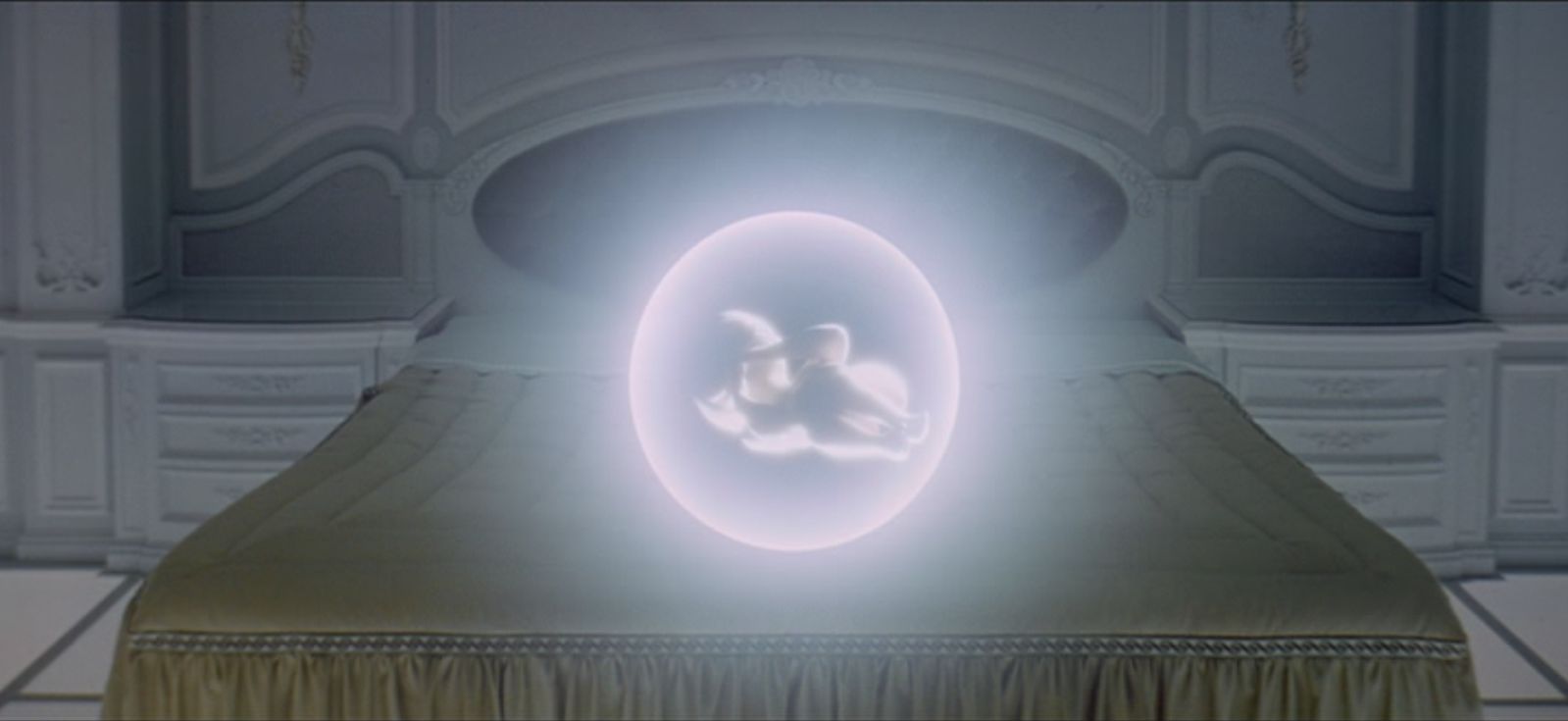

And then, the other moment that just makes me straight-up lose my shit, every time: the cut back to the bed, with the Star-Child floating there. As with the first human with the bone club, Kubrick does this with the elements of cinema, creating its power not just with the image but with the hard cut to it, and the recurrence of Zarathustra on the soundtrack. We heard this when we saw the beginning of humanity, when the first primate became human; now we hear and see the first human become whatever’s next. The film ends, as an Odyssey has to, with the return of the wanderer, the first new being coming back to the old world. Whatever the word “humanist” means, I think it applies to a filmmaker who made a myth of the entirety of humanity. It is, exactly, awesome.

And then, the other moment that just makes me straight-up lose my shit, every time: the cut back to the bed, with the Star-Child floating there. As with the first human with the bone club, Kubrick does this with the elements of cinema, creating its power not just with the image but with the hard cut to it, and the recurrence of Zarathustra on the soundtrack. We heard this when we saw the beginning of humanity, when the first primate became human; now we hear and see the first human become whatever’s next. The film ends, as an Odyssey has to, with the return of the wanderer, the first new being coming back to the old world. Whatever the word “humanist” means, I think it applies to a filmmaker who made a myth of the entirety of humanity. It is, exactly, awesome.

We associate awe with our experience of God because awe is what we feel in the presence of the Creation; but the power of creation was given to us, as well. (For a hardcore Yahwist like me, it’s literally the first act of Creation.) Do it right, do it on this level, and humans can create that feeling of awe too, and that is what 2001 does. It inspires, and think on that word, in-spiritus; we draw in its soul. Great art becomes part of us and transforms us, for at least the rest of our lives. Clarke wrote “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”; 2001 shows us that any sufficiently powerful art is indistinguishable from the Divine.

[Fun fact: in 1989, James Bond (no, the other one) created Cinema Borealis, a three-night event in Chicago’s Lincoln Park. He set up a 70-foot-diagonal screen with an utterly boss sound system in the park, and showed a different movie each night and I attended all three. Ran was Friday night, Days of Heaven Sunday. Saturday night was a new print of 2001; I invited some friends and we went with a picnic blanket. It rained lightly for the whole movie; when it was over, we abandoned the blanket and ran six blocks to a hot dog joint under the El. It was, as it should be, one of the greatest nights of my life.]Previously: Dr. Strangelove (1964)

Next: The Lost Worlds of 2001