Not too long ago, I’d go to Boston City Hall every weekday and look for stories. I’d read things, talk to people and listen to them talk – so much talking, at press conferences and commission meetings and public hearings. So many words, so much information, and a big part of my job was filtering it. Tuning out or turning down things that weren’t relevant to what I was looking for or grabbing on to a piece of info that showed promise and shaping it into a story, or at least a part of a story, setting it next to other pieces that gave it context and definition. I’d do this, pump out something that rarely went longer than 500 words (I am capable of this brevity, I swear), and come back the next day, ready to do it again.

In the fall of 2018, a few months after I had stopped doing this, Frederick Wiseman and his team came to City Hall and hung around until the beginning of 2019. If they read things they kept that to themselves and of course talking to people is not part of Wiseman’s MO, nor is providing backstory or context to what is on camera. No, what they did was watch and listen and the biggest adjustment for a person like me is getting a handle on Wiseman’s filter, what he lets through in individual scenes and in the movie as a whole. He has four and a half hours, as opposed to something meant to be read in two and a half minutes, and he seems more interested in the currents than the grit they carry. The movie ends with a shot of the Atlantic lapping up to a pier in Boston Harbor, he’s charting the tides of an institution that aspires to a similar power.

By my count, in City Hall we see activity on floors 1, 2, 3, 5 (there is no fourth floor!), 6 and 7 of City Hall, I am fairly sure 8 is in there but doubtful 9, the top floor, makes an appearance. A same-sex marriage is officiated in the City Clerk’s office, several parking tickets are appealed in small rooms, 311 operators listen to complaints in a monitor-heavy command center. Mayor Marty Walsh holds a press conference in the Eagle Room, so named after a statue in its corner, off his fifth floor office. If there’s a distilled example of Wiseman’s methods it’s here: The Red Sox have just won the World Series and Walsh is describing safety precautions for the victory parade. We will see no footage of the Sox playing ball or the parade itself but we will see Walsh at a podium, droning on about good behavior. The institution is the focus here, the work and talk by the government.

But Wiseman knows how much of that happens outside City Hall itself, so we travel around the city. To other government buildings, to community centers hosting neighborhood meetings, to fancy private offices where public officials talk with businessmen and nonprofits. One of the longest chunks of the movie takes place at Faneuil Hall, which the city’s Veterans Services department uses to host an event where veterans can talk about their experiences. A woman in her 80s talks about nursing and crying with men who lost limbs in World War II; a man in his late 30s talks about serving in Iraq and Afghanistan and bonding with his old neighbor, a WWII vet and a “grouchy prick” who eventually gives the younger man a souvenir from his time in the Pacific theater — a Crown Royal bag filled with gold teeth.

The man telling this story knows what he’s saying, he follows this by making the connection between this bag and his neighbor’s general anti-social behavior. But a lot of other people talking as they do their institutional work are less self-aware. As winter comes on, officials gather to discuss what to do about sheltering the homeless and a transit cop says it has to be different than last year. (Last year, the movie doesn’t explain, is when record freezing temperatures led to people being housed overnight in South Station, a large subway/bus/train hub.) “The folks that are paying a lot of rent inside South Station were beside themselves, commuters coming in the morning were beside themselves,” the cop says about the station’s emergency occupants. “I say a vast majority of them weren’t even homeless.” Another woman, possibly an MBTA official, chimes in a few minutes later. “As a public position, we are in a strong position to say the T is stepping up to do what it does best: Transportation.” She has an embarrassed laugh there, as if even she can’t believe she’s saying the much-hated T is doing its job well. The meeting moves on to its next topic.

The government gives a space for veterans, the government tries to find a space for the homeless. The government talks about “resiliency” (which “helps Boston plan for and deal with catastrophes and slow-moving disasters, like persistent racial and economic inequality” according to the city’s website) at a Rockefeller Foundation conference at Boston University, where a guy (Chief of Economic Development John Barros, not that he’s named) talks about developing a project that will be put out to bid to create a pipeline for jobs. The government, in the form of Walsh, speaks about the slow-moving disaster of climate change at storied and fancy-pants law firm Nutter, McLennen & Fish at their Seaport office. Walsh is the default protagonist of the movie. Boston is a strong mayor city and Walsh is a mayor who gets out and about.

He gets a lengthy scene at the start of the movie, talking about how trauma counselors need to work with residents after violent events and while Wiseman frequently intercuts his many, many meeting scenes with looks at the audience (never in “gotcha” mode, he’s not trying to find yawns), he lets Walsh speak mostly uninterrupted here about crime and mental health services. “I’m taking criticism for Carlos Henriquez,” Walsh says, adding that Henriquez was going to be someone who helped lead that effort of coordinating trauma services and oh shit my filter is shorting out right now because

that makes it sound like Enriquez is a community activist which is true, he’s done a lot of work in that regard, but he also was a state rep who got convicted of punching a woman in the chest for refusing to have sex with him and got sentenced to jail and expelled from the Legislature earlier in the decade and Walsh is a guy who believes in second chances and hired him to do this work but also didn’t exactly make a big deal about paying this guy $90,000 in taxpayer money so when the papers found out there was a big shitshow and Henriquez resigned and sorry, sorry, I’ll turn the filter off, let’s get back to Walsh and

“Everyone’s looking for a blame,” Walsh says, about when a person is murdered in his city. He talks about some more plans for counselors.

It’s not all talk. Just as government does, City Hall extends throughout the city, into everyone’s lives, and a lot of people are off doing things as they talk. We watch a stressed-looking building inspector poking through the bones of a condo under construction and checking with the foreman (who of course has an Irish burr). We watch a calm and kind property inspector give a man cleaning tips so he won’t have a rat problem, the man, who seems nice if a bit out of it, says this will help as he tries to fight eviction proceedings being leveled against him by his own brother. We watch a worker at the City Archives, way out on the end of West Roxbury, pull out a drawer with “prehistoric clams,” who hung around when the whole area was under water thousands of years ago and got stuck in clay that was used to construct houses a century ago. “I just think they’re really cool to find,” he says.

And sometimes there’s no talk at all. We watch a garbage truck crushing mattresses and grills, we see a guy laying down parking tickets on a row of cars. We watch a road crew create a bike lane, squirting out glue and spreading it out and throwing down dusty red gravel. We watch people passing through the metal detector at City Hall’s main entrance, a passage I have made hundreds of times and something that Wiseman’s filter here requires me to actually see instead of slough through. We see two men at Franklin Park, quietly clipping and tending to plants in a greenhouse, soft folk music playing from a boombox while the wind gusts through leafless trees and whips the ragged tarps covering mounds of salt and sand piled for the coming snow, it is a lovely moment of peace and work, an oasis. You can tell by the way one man pokes at his soil that he’s talking to it, communicating with a clarity that eludes the people at their endless meetings.

Because these scenes of the government at work in active ways act as rhythm and Wiseman slowly, subtly, uses the verbiage and planning of the meetings as harmony to a disturbing melody. The Department of Neighborhood Development, which was in the meeting with that MBTA cop questioning whether people trying to avoid freezing to death are technically homeless, is first introduced talking about another housing problem, how to avoid people being evicted. There is a lot of shop talk about this, interesting things that my filter automatically engages and works to distill, but stuff that Wiseman lets play out in full, creating a quicksand that it seems impossible to escape. At one point, a Black guy speaks up: “If we’re really concerned about what we’re doing, we need to also think about a community land trust for folks who really can’t do anything. They could go there and it’d be a safe zone from generation to generation, why can’t we do that? Other places have done that.” Well, Boston has done a few of these, just for the record, but this certainly seems like an effective if non-market-based solution to the problem, unlike the things that have been discussed for the last 10 minutes. DND director Sheila Dillon sort of nods in recognition, and Wiseman cuts away, the action shied away from.

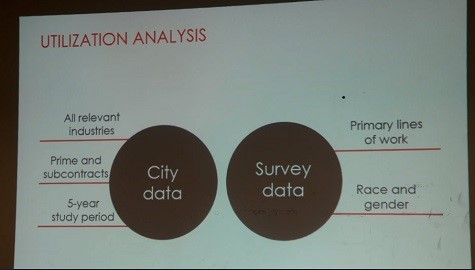

Much later, the city hosts a meeting to discuss whether minority and women-owned businesses face any barriers when it comes to obtaining city contracts and how this needs to be studied. There is some mind-numbing PowerPoint that is seemingly intended to put people to sleep, but then a guy in the audience starts talking, politely but incredulously wondering what the hell there is to talk about, and Wiseman moves away from the dapper but aloof bureaucrat host and lets him have the floor:

Educate me a little bit about these disparity studies. I’ve been in this business for the past 30 years… When you say ‘disparity study,’ meaning a study, that there is a doubt — is there a doubt this exists? Because I’m finding these 30 years a difficulty for me in these contracts to achieve, I don’t think there should be a kind of a doubt … Not too long ago I was the minority in a state contract, I was a third-tier contract so they could fill a minority quota, why did I not go directly to the general contract? There are things, connections made … for the past 30 years I can feel it, if the dollar is ticking green all of a sudden all of the qualifications, I can’t meet that… there is something to keep me on the $200,000 projects, where the dollar is greener the disparity is there.

This man is throwing chunks of pure gold into my filter, I can barely keep up. And neither can the guy hosting the meeting, who tries to hem and haw his way out of this. “I wouldn’t use the word ‘doubt,’ it’s an exercise in gathering evidence so the city has evidence it needs to tailor its program appropriately.” Hard cut to John Barros, last seen smooth-talking rich folks at BU and a guy who is at the pay grade to talk turkey, stepping in to smooth things over. “There is no doubt!” Barros soothes, saying this a top priority of the mayor’s. It sure sounds important. There is no indication the study will not continue.

A little later, at a community meeting about a big construction project going forward, a woman raises objections. She’s Black, like the guy at the DND meeting was Black. I don’t know the ethnicity of the guy at the minority business meeting (my filter is set to record NAME AND TITLE, Wiseman’s is not) but by definition he’s a minority business person. Certain people here seem to be raising objections. The project is in Roxbury, one of the most Black and brown neighborhoods of Boston (which, as is noted in passing during the documentary, is a minority-majority city), and it’s being handled by Cruz Construction, a third-generation minority-owned business. “There should be meaningful long-term community benefits,” the woman says, her face registering that this is a battle already lost. “It shouldn’t be a shot in the arm, it should be long-term. It should build equity, that’s my concern… Community benefits should resonate and come from the community.” The Cruz Construction leader tells her that he understands but the company has already made agreements for community benefits, to give office space to the Boston NAACP, and going back on that would cause a whole lot of problems, can you understand? And all of a sudden it becomes a bit clearer how a business can get to that place where the dollar is greener, how it can play the game with the players that are recognized. And how City Hall will organize these meetings and even let you speak at them, but that the real talk happened a while ago.

These meetings, and a long neighborhood discussion of a proposed marijuana dispensary, are out in the community. Many of the other meetings we see in City Hall, like the DND ones, are on that department level with people trying to do work and discussing things openly, which is to say in private. That’s not a City Hall available to most people, although I poked and prodded wherever I could legally go. I went where I could find things that fit my filter, where City Hall wasn’t working and where people were pissed about it, or where City Hall was working and people would rather not talk about it. Liquor board hearings for bars that fucked up were great for the latter (and while I may have missed something, from what I can tell Wiseman somehow made a 4.5 hour movie about Boston where booze is not seen and not even mentioned), but places where people wanted to get mad about City Hall were even easier to find. Zoning board meetings about those damn new condos, larger Planning and Development meetings about giant gentrifying projects. Plenty of people coming to City Hall the building, lining these shitty rooms under fluorescent lights to yell at some bureaucrat about City Hall the institution fucking up their lives.

And of course there were the regular City Council meetings, where there was usually a specific agenda item people were up in arms about but also a general opportunity to complain. Wiseman is a subtle director but here his subtlety requires a bit of context — there are maybe two total minutes of city councilors on film here, solely in the background, and that is because the City Council is an almost entirely useless body, possessed of extremely limited power and unwilling to use what they have (they must approve the budget and could theoretically deny it, they never do). It is a place for grandstanding and empty threats, so in a study of an institution at work Wiseman ignores it entirely. But this is the place where the people of Boston are shunted when they’re concerned, the place in the actual City Hall where they can always go to yell, and it is curious that we never see this, even as counterpoint to the functioning of the institution without them.

Between setpieces of talk Wiseman shows us clips of City Hall itself, the hated giant Brutalist toadstool looming over a desolate plain of brick, and dozens of other buildings, churches and storefronts and schools across the city, a trainspotting of Boston neighborhoods (I was inordinately pleased with myself to regard a building with skepticism and confirm it is actually just over the border in the town of Brookline. SHUT IT DOWN, WISEMAN). But these shots rarely contain people and the longer this goes on, the more odd the disparity becomes — a city of structures but no humans. More often than not, City Hall has people making some kind of a stink outside of its front doors, a dozen or a hundred people listening to a person with a bullhorn yelling about something. That’s not in Wiseman’s filter. The gladhanders and dealmakers and furious neighbors outside the Zoning Board on the eighth floor are not in his filter. The people milling around the fifth floor, blocking the elevator outside the mayor’s office as they wait to get into a useless City Council hearing, they’re not in Wiseman’s filter. The building Wiseman is studying, the institution it represents, is remarkably empty of the people who would speak against it. But maybe this is by design. Does a fish have a claim on the ocean? Does a boat have a claim on the tide?

The cameras of City Hall are unobtrusive. The edits — the filterings — of City Hall are orchestrated with a confidence that only comes with long experience. But I think back to the very beginning of the movie, where the title card is shown in the trademarked font/style made specifically for the city of Boston (at a six-figure cost, if I’m reading the city’s financials right, but you didn’t hear that from Wiseman). Clean, sans-serif text in Snow White, Charles Blue, Optimistic Blue and of course, Freedom Trail Red. It’s how the city itself would title the movie.

And it makes me think how the movie seems aligned with the subject. The absences — of dissent, of opposition — contain a message, but only if you know they are absent. Otherwise they’re just silences waiting to be filled with talk.

And maybe a movie that is 80 percent talk can’t help but be in sync with an institution that is based on talking the talk without always walking the walk. Not that they aren’t trying, truly. City Hall shows people who care about their jobs and I think that’s why many people responded to it so favorably this year. Officials working instead of looting, listening to people instead of ignoring their cries, a guy like Walsh talking about his struggle with alcoholism instead of proclaiming his superiority to everyone who isn’t him — it’s nice to see government actually talking a good game instead of telling me to go fuck myself. But talk is cheap, that’s why it’s so plentiful, ever-refreshing like the ocean’s waves.

The movie ends with talk, of course, dropping in on Walsh’s State of the City address in early January. Walsh talks about how he pledged to expand the middle class a year ago and has done so. He has less to say about another promise from last year’s speech (which of course is not brought up in the movie), his promise to restore addiction and mental health services at a facility shut for reasons outside his control, which hasn’t gotten very far and will not take place barring an armed occupation of the city of Quincy. It’s a new year, it’s time to celebrate and create new promises to talk about in meetings that may or may not include the citizens those promises are meant to help. The tide goes in, the tide goes out.