Chungking Express is a movie about heartbreak and longing. It’s a classic in the category of films about how lonely city life can be, alongside Collateral and Shame – how you can be surrounded by people and systems (even ones you fit into) and feel completely alone. Much of the action is characters playing out odd little rituals that attribute meaning to almost random objects to feel a sense of connection to someone. The filmmaking backs this up; the camera is curious, distant, surveying the characters like a patron at a bar looking over from his drink (literally at one point), and the narration has the characters confessing their intimate thoughts to us in near-present tense. Travis Bickle’s narration in Taxi Driver is thoughtful, past tense – a carefully worked out manifesto. The narrators here are theorising and explaining, but it feels more like they’re thinking out loud about their loneliness in real time.

This, of course, raises the question of why you’d want to feel loneliness for two hours.

One question that horror fans tend to have to answer over and over again is why they would subject themselves to something horrific when fear is obviously bad. Said horror fans almost always respond to this with talk about how it’s a therapeutic experience with roots in storytelling going back to campfire stories cavemen told; very rarely do they just outright say ‘fear is obviously good and if you can’t even handle it in the complete safety of a movie experience, that’s a You problem’. Similarly, it’s good to feel that heartbreak of Chungking Express – to face it as unflinchingly as David Lynch faces evil. The conflation of life and fiction is always presented as a negative; men and women who think the world works like the romance movies they grew up watching (even when they didn’t actually understand what was happening), people who constantly joke like there’s a studio audience watching them, and perhaps the most iconic conflation of fiction with reality of the Tens and Twenties, people who are incapable of understanding politics without attributing the names of Harry Potter characters to the major players.

I believe these people are all fundamentally correct for conflating fiction and reality – they’re just doing it badly. I have compared far too many people to Shield characters to be able to call Harry Potter fans on it. One of the things fiction does is expand our empathy. The first difference, of course, is that I go to the effort of genuinely trying to empathise with people – when I compare someone to a Shield character, I mean it in a very specific way. I may refer to someone as like Shane in that they’re impulsive, or I may use it to mean that they feel things very deeply, or I may use it to mean that they are bone-deep racists when a genuine loathing for non-white people (as opposed to, like, Vic, who doesn’t hate nonwhite people but is more than willing to use racist tactics to get what he wants). I’m not just saying “Trump is Voldemort because I don’t like him”.

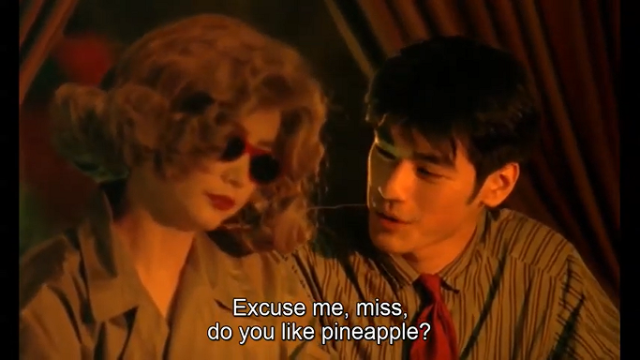

The second difference is that I think these comparisons should be treated as temporary markers describing only the current moment. Emotions are temporary and quick to sway; subject to hormones and weather as much as anything anybody actually does. One reason people ‘acting like they’re a character in a movie’ is annoying is because they try to warp reality to match what happened in the movie; I think, however, it’s good to use movies as labels for one’s current emotion. It’s helpful to be able to label emotions so you can process and express them. In a break-up, a missed opportunity, or a simple moment of romantic longing, one can recognise one is now a character in Chungking Express – not in the sense of deciding the best thing to do is to eat a shitload of canned pineapple or break into someone’s house to clean it for them, but in realising one is acting out an odd little ritual and finding a better, more helpful ritual, then watching the emotion sap away and be replaced by another one from another movie (as opposed to unhelpful wallowing or destructive behaviour). It’s good to face negative emotions head-on, and it’s easier to do that when you associate them with good-ass movies.