Career Killers is an ongoing series where we discuss films that have sunk studios, derailed genres, ended movements, and left their writers, directors, or stars unemployable. This week, Babalugats on the film Rollerball and the series of increasingly terrible decisions that landed John McTiernan in prison.

The Career

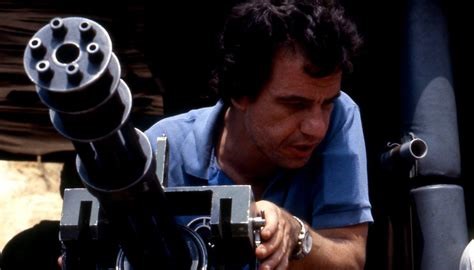

It’s not uncommon for “journeymen” directors to have a long stretch of paying dues, whether through television, or Roger Corman cheapos, or second unit work, or stunt coordinating, or music videos, or advertising, or anything else that will cement their reputation as being a hired hand rather than a true artist, before they ever get a shot directing a worthwhile movie. But John McTiernan’s career wasn’t like that. His first job in Hollywood was directing his own script, the reasonably budgeted Nomads, with future movie star Pierce Brosnan (here pre-Bond and inexplicably French). Nomads is spooky and atmospheric, and a very underrated film. Though it didn’t get great reviews or do huge box office, it did catch the eye of a young Arnold Schwarzenegger, who hired McTiernan to direct a little movie he was trying to get off the ground called Predator. Predator was a massive hit, and McTiernan would follow with two more genre-defining behemoths in Die Hard and Hunt For Red October before reuniting with Sean Connery for Medicine Man, a moderately well reviewed and moderately profitable film, despite lacking the cultural impact of his previous work.

And then came Last Action Hero, one of the most notorious flops of all time. Last Action Hero is a great movie, an action pastiche and affectionate parody with a sharp script by Shane Black and a very funny self-aware performance by Arnold Schwarzenegger, and it’s become a minor cult classic (albeit with a significant generational divide). But it was a few years ahead of the curve on that sort of semi-parody thing, and egregiously mis-advertised. Last Action Hero was a movie that came up a lot when I was looking for possible subjects, but all three principals, Schwarzenegger, Black, and McTiernan, came out of it pretty much unscathed.

For his part, McTiernan bounced back with a return to the Die Hard franchise (and arguably topped the original). And with Last Action Hero now looking more like a fluke than a downward trend, the studios were once again willing to gamble on him, this time with a loose adaptation of Beowulf starring (an inexplicably Persian) Antonio Banderas. 13 Warriors had a notoriously difficult shoot, and after McTiernan’s original cut (then under the far better title, Eaters of the Dead) tested poorly, its release was delayed for years while the studio and writer and replacement director Michael Crichton hacked away at it. McTiernan’s cut has never been released, but the finished product is actually quite good (although the Crichton reshoots stick out like a sore thumb) and has also developed a minor cult following. However, this wasn’t enough to save the film from being a huge critical and commercial failure.

Luckily for McTiernan, the long delay was enough for him to complete his next project, reuniting with the no longer French Pierce Brosnan for a remake of The Thomas Crown Affair, which proved to be a solid commercial and critical success. McTiernan entered the new millennium still in demand but with a deeply tarnished reputation and in need of another big hit.

The Film

The original Rollerball is exactly the sort of film that Hollywood inexplicably loves to remake. One of those odd little movies that probably shouldn’t have even worked the first time. The things that work about the movie (the strange tone, that particularly 70s mix of being very silly on a surface level while also being melancholy and thoughtful and meandering, James Caan’s perfect central performance) are impossible to replicate and the things that you’re left with (a goofy fictional sport, a dystopian future that is already obsolete by a few decades, and middling name recognition) are almost more of a liability than an asset. But McTiernan had just spun gold out of a similarly misguided remake of another oddly toned Norman Jewison movie built around an iconic performance, so Hollywood decided to press its luck.

Rollerball opens in medias res with our hero (one of the more disposable Hollywood Chrises) in an unsanctioned illegal street luge race as the buttiest of studio butt rock blares over the soundtrack. It is 2002, and it couldn’t be any other year. The race takes place at rush hour across a series of busy intersections and soon attracts the attention of the police who decide, despite the limited escape options available to the lugers, not to simply wait at the bottom of the hill, but to chase the lugers down it, causing as much mayhem themselves as the criminals they’re after. All of this is filmed, as the entire movie will be filmed, in a hyperactive editing style derivative of Micheal Bay and his imitators rather than the more controlled and composed style that McTeirren mastered over the previous two decades.

Despite the inherently straightforward nature of car vs luge chase, Chris manages to lose the cops. A Porsche driven by LL Cool J pulls alongside him. Chris manages to board with a suitably thrilling amount of difficulty, and Cool J deftly makes his escape. The police do not pursue. You’re probably thinking that LL Cool J is part of the gang, but no. Turns out he was just driving by, somehow recognized his friend mid luge, and deduced, correctly, that he would want to jump off that luge in order to escape the race he had entered into. Cool J recommends that Chris join his rollerball team. Chris seems resistant but the next scene is a rollerball match, and Chris is the star player.

The rollerball match is cut between the match itself and a music video where a rock band appears to be playing a gig in the audience. We are given the rules of the game by the play-play guy who seems more like Alex Jones than Vin Scully. There are both not enough rules and entirely too many rules. The sport could best be described as a hybrid between a roller derby, motocross, the WWE, and Cirque du Soleil. It is impossible to tell at any given time who is winning, which players have or lack talent, or what any particular player’s objective is at the moment. One player is murdered on the course, but it doesn’t interrupt the action.

After the match the players go to one of those futuristic coed locker rooms like they have in Starship Troopers or Europe, and then immediately hop into their Ferraris for another hyperactivity edited race to the club, and we are a solid half hour into this 98 minute movie and we have seen nothing but hyperactively edited chase scenes. I don’t think we’ve gotten a single shot that’s held for more than a second. My head is throbbing and my eyes are bleeding.

Finally in the club the movie starts laying out the plot, and I am immediately bored and wish we could get back to chase scenes. There is a conspiracy to make the game more violent and drive up ratings. But this isn’t really a conspiracy since the whole point of the sport is that it’s hyper-violent. It’s like discovering that the UFC doesn’t care about the safety of its fighters. At one point LL Cool J tells Chris, “We play, we win, and if it gets too sick, we walk” and it’s just the movie flat out acknowledging that there’s no stakes to this story whatsoever.

The world building is also a mess. Sometimes it seems like rollerball is a huge sport and its stars are multimillionaires and international celebrities. Other times it seems like a backwater rec league. Chris turned down the NHL’s #1 pick to be here and the heroes are hounded by paparazzi, but Cool J has a second job as an accountant. League owner and small time despot Jean Reno remarks that he’s “this close to getting a North American cable deal”, making the sport somewhat less lucrative than professional bowling or competitive darts. Like, just quit. Stop rollerballing and all your rollerball problems will be solved.

There’s a long action scene filmed entirely in night vision that ends with Cool J getting assassinated. This is also part of the conspiracy and probably a big reason why Reno hasn’t been able to get that cable deal.

Rebecca Romijn (who has been in the movie the whole time as Chris’s love interest/teammate/secret revolutionary, and is not bad considering what she’s given to work with) is put in peril and Chris is forced to play in the championship to save her. This ends up sparking a bloody, bloody revolution. The last few minutes are gory gonzo hyper-violent action schlock. Had the movie embraced this over the first 80 minutes it could have been, not good exactly, but it could have had a certain charm to it.

The Fallout

Rollerball had a notoriously troubled production. The initial script for the remake hued closely to the tone and politics of the original, but when McTiernan signed on he was interested in making something more over the top; the bloody, sexy, hard R, WWE-esque extravaganza that people had expected from Last Action Hero. This was the film that was shot, but after a disastrous screening the producers decided to radically retool it. 30 minutes were cut from the film, big black censor bars were placed over the nudity, blood was cgi-ed to look like sweat, and the swearing was awkwardly dubbed over. The score was also dropped for sounding “too Arabic” and McTiernan was ordered to reshoot scenes with all white extras because the film was “too Asain”. The inexplicable night vision sequence also came from these reshoots and was intended solely as a cost cutting measure. McTiernan became convinced that producer Charles Roven was intentionally sabotaging the film, and hired private detective Anthony Pellicano to dig up dirt on him, hoping to blackmail his way back into creative control. Apparently, this dirt was underwhelming because the film that was released is atrocious.

Rollerball was released on Feb 8, 2002. It holds a 3% on Rotten Tomatoes and grossed $25 million worldwide against a $70 million production budget. McTiernan limped away to work on Basic, with John Travolta and Samuel L Jackson, which proved to be another critical and commercial failure (it’s fine).

In August of 2002 Anita Busch, a journalist working for The Hollywood Reporter, found her car vandalized. The windshield had been smashed and a dead fish, a red rose, and a sign reading “STOP” left on the hood. She reported this to the police. Three months later the LAPD raided Anthony Pellicano’s office. Pellicano turned over some guns but neglected to inform the police of the homemade bombs and military grade C-4 he was hiding in his safe. He would later plead guilty to illegal possession of dangerous materials and was sentenced to 3 years in prison. On February 3, 2006, the day before he was scheduled to be released, he was transferred to federal prison and indicted on 110 counts including racketeering, conspiracy, witness tampering, extortion, identity theft, destruction of evidence, and wiretapping. He would eventually be sentenced to 15 years. At the time the Pellicano case was billed as the scandal of the century. The notorious fixer had seemingly worked for or against every major Hollywood celebrity or power player at one time or another. But ultimately, little came of it. Pellicano did his time, mostly kept his mouth shut, and was released on Mar 22, 2019.

On February 13, 2006, four years after the disastrous premiere of Rollerball, John McTiernan received a phone call from an FBI agent who asked him about hiring Pellicano through his divorce attorney in the 90s. At the end of the call, the agent asked if that had been the only time McTiernan had hired Pellicano. He said that it had. Two weeks later he was arrested for lying to the FBI.

McTiernan initially pled guilty to avoid a prison sentence, but the prosecutor later decided that he hadn’t been cooperative enough and pushed for jail time anyway. One of the prosecutors working the case was a failed actor who had (allegedly) been passed over for roles in both Die Hard and Hunt for Red October. It is the policy of The Solute not to cast aspersions on any rat fink feds and in particular not on petty grudge-holding feds, so we will leave it to the readers to decide whether or not McTiernan’s prosecution was the result of a personal grudge, but we will quietly and respectfully point out that McTiernan was the only Hollywood figure who faced prosecution in connection to Pellicano.

Now facing jail time, McTiernan tried to withdraw his guilty plea, but this was rejected and he was sentenced to four months in a federal prison camp. McTiernan appealed this decision and on February 24, 2009 his guilty plea was withdrawn, and he was granted a new trial. The prosecutor immediately added a second count of lying to the FBI as well as one count of perjury (for withdrawing his plea) in retaliation. After various lines of defense were denied by the court, McTiernan, now facing a potential 5 years in prison, once again pled guilty. He was sentenced to a year in prison, and three years of parole, but allowed the opportunity to appeal the decision based on the grounds that the state’s only evidence was an illegally produced recording. McTiernan appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, but they declined to hear the case.

On April 3rd, 2013, McTiernan finally surrendered to prison. With the legal fees piling up, and his last film a decade behind him, McTiernan was left to navigate a difficult bankruptcy from behind bars. (Although I don’t think they actually have bars in the white collar minimum security Federal Prison Camp he was sentenced to).

McTiernan has been free for several years now (in fact even Pellicano is free now) and rumors of a comeback film have come and gone. He is currently attached to a Sci-Fi action thriller with Uma Thurman, but so far nothing has come of it.

The Verdict

Time Served.

There’s no defense of Rollerball on cinematic grounds, and even if McTiernan had gotten his way it would likely still have been a bad movie. His follow-up, Basic, while functional was not a return to form. And while his jail sentence was unjustified he shouldn’t have been spying on people and you can’t blame anyone for not wanting to work with him at that point.

Still, this was the defining action director of the best period of American action cinema. It would be a shame if we never saw his Fury Road.