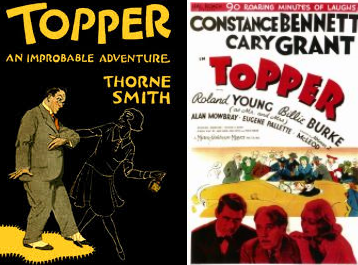

It’s strange to remember that Visual Effects, as a category, is an offshoot of the defunct Special Effects category. This is an uneven one; in three of its years, it might as well have been an honorary award, since there was only one nominee in the category. In a dozen more years, it was between two. I don’t pretend to understand why; in many of the years in question, I can without trying come up with at least one more suggestion. Now, I can’t prove that the success of Topper is one of the reasons for the creation of the category. I will, however, point out that both its sequels were nominated in the category, admittedly both winning to even more obscure movies.

Topper, the book, is the story of a quiet man named Cosmo Topper. He works in a bank. He lives in a quiet, middle class neighbourhood with his shrewish wife. He has a cat to give him some happiness; she has dyspepsia. Recently, people in their town named George and Marion Kerby died in a car accident; Topper, on a whim and in a mood of discontent, buys their old car after it’s been fixed up. Possibly because of this, the Kerbys manifest in his life. He eventually ends up running off with Marion and spends a summer with her and two other ghosts, plus the half-manifesting ghost of a dog.

Topper, the movie, is the story of a quiet man named Cosmo Topper (Roland Young). He’s an executive in a bank. He lives in a quiet, upper class neighbourhood with his ditzy wife (Billie Burke). They have a butler (Alan Mowbray). The ostensible head of his bank is George Kerby (Cary Grant), who leads a wild and dissolute life with his wife, Marion (Constance Bennett), until they are killed in a car accident; Topper, on a whim, buys their old car after it’s been fixed up. In part because of this, the Kerbys manifest in his life. They decide that they need to fix Topper’s life as a good deed in order to go to Heaven.

The two are very much alike until suddenly they are very much not. There’s a lot more George in the movie, but since he’s Cary Grant, I think we’re all grateful for that. What’s interesting, though, is the last third of the book, which simply does not appear in the movie at all. Now, that’s in part because I got relatively close to the end and said, “Wait, did Topper just sleep with Marion Kerby?” And you can’t have that, or even the extended bits with Topper, the Colonel, Mrs. Hart, and Marion Kerby, with the Colonel’s dog, Oscar. Because he has run away from his wife for an entire summer, and the ghosts steal from various proprietors—including bootleg liquor—and what with one thing and another, no.

More, the difference between Book-Mrs. Topper and Movie-Mrs. Topper is enormous. Billie Burke is dim and shallow, simply not noticing her husband’s restlessness. When she’s aware that Topper is doing things with the invisible Marion, it hurts her. Not her pride, her heart. She loves Topper in her own dingbat fashion. In the book, while she’s allowed to change with Topper’s summer with the spirits, she genuinely enjoys causing him distress. She doesn’t care if he’s right or wrong, so long as he admits he’s wrong. With him gone, she realizes how much she loves him and becomes a better, softer person, but my Gods she’s awful through most of it.

There’s something of a difference in theology in the two stories. In the book, the assorted spirits call themselves low-plane spirits; they are pottering about on Earth because they find the more ethereal planes boring. They’d rather hang about on Earth, teasing mortals and eating and drinking. (The physics of this are left to the imagination, because the ghosts refuse to explain.) In the book, the Kerbys decide for themselves that the reason they aren’t ascending is that they have to do good deeds first. They make Topper their good deed, because they think he needs to be more like they are.

The truth, in both cases, is somewhere in between. Topper is terribly repressed and secretly unhappy, and he does want a bit more of a thrill. It is indeed why he buys the Kerbys’ car in both versions. In both, there’s also more than a hint of a lust for Marion that predates her death. A passion, if you’d rather, as it does seem to be as much about what she represents as anything else. Topper hasn’t much of a hankering to be George, but he’d very much like to be the sort of person who could have fun with Marion.

The special effects on the movie are indeed quite impressive. Apparently, Grant and Bennett enjoyed their scenes spent dematerialized, because they just had to record their lines. The special effects people did all the rest of the work. Obviously, it’s all practical effects, and beyond that, I haven’t the slightest idea how no little of it was done. Quite a lot of the time, the Kerbys are invisible. Obviously, this is for comedy’s sake; the internal reasoning is that materializing takes up some of their “ectoplasm,” and they only have so much of it to spare. Either way, the work to make it seem as though they’re in the scene is done exceedingly well.

While I was researching this article, I watched the second movie—Topper Takes a Trip—for the first time in years. It doesn’t come up much, doubtless because it isn’t, one must admit, very good. What’s interesting, though, is that there’s a scene in it where Marion, returned to help the Toppers because reasons, decides that the best way to help Topper get money, which he needs because reasons, is to cheat in a casino. The way she monkeys with the roulette wheel was lifted almost whole cloth into Blackbeard’s Ghost, and while it’s almost equally likely two different scriptwriters had the same idea, it’s still a little astonishing.

I don’t have ghosts helping me out; I rely on people who support my Patreon or Ko-fi! And next month, we’ll be taking a jaunt back into the Disney archives for That Darn Cat!