There must be a great deal of comfort to a Freudian world view. The idea that someone is mentally ill because she wished, in a fit of anger, for the death of her father when she was a child must be much easier to deal with because it can be fixed. If it’s inherent to the person, something in the makeup of their brain, that can’t be fixed. It can be worked with, treated, dealt with, but not fixed. And so the undescribed, undetailed mental illness of the book becomes a Freudian tangle.

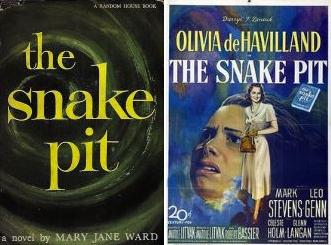

The book of The Snake Pit is not, according to author Mary Jane Ward, a fictionalized version of her own experiences in a mental hospital. It is, however, the story of Virginia Cunningham of Evanston, Illinois. Virginia was living in New York with her husband, Robert, when she had a nervous breakdown. The book is told from Virginia’s perspective, foggy as it is. She is in what is quite clearly a public mental hospital, one that operates on a sliding scale. She undergoes various treatments, including shock therapy and hydrotherapy, all while trying to cling to herself.

In the movie, Robert Cunningham (Mark Stevens) tells Dr. Kik (Leo Genn) about his wife’s past. Eventually, we get to Virginia’s own perspective. She is Olivia de Havilland; we see her through electroshock and hydrotherapy, all right, but also drug-assisted hypnosis and analysis. Slowly, she gets well by working out that all her problems stem from when she was a child. Among other issues, she was angry at her father when he died.

In neither one is Virginia unintelligent. She’s explicitly a published author. She is trying very hard to find her feet; she spends all of both trying to reach for sanity. She is not the only one. While some of the people who she meets are clearly bad enough they will likely require lifelong institutionalization, it’s clear that most of them are in a similar place as she is.

Unfortunately, where they all are is an overworked, understaffed, underfunded mental hospital in the 1940s. The book never mentions Virginia’s having any talk therapy—she was analyzed by Dr. Kyk during the time at which she was getting electroshock, and she doesn’t remember it. She barely sees a doctor again after that point. In the movie, her analysis continues after the electroshock and is why she is cured. The other doctors express astonishment that Kyk’s methods bring about Virginia’s cure but don’t really seem to have any successful options of their own.

Paradoxically, the Freudian aspect of the movie robs Virginia of her agency in a way that the mysterious illness of the book does not. In the book, Virginia pretty much gets better because she is determined to do so—we even get a second doctor at the end who explicitly disagrees with Dr. Kyk about several things, not least the cause of Virginia’s illness. In the movie, it’s all Dr. Kyk’s miracle cure. There’s also a whole tedious thing about how she knows she’s better because she’s not in love with him anymore, possibly the silliest Freudian concept.

It’s frustrating, because there’s a good movie buried under there. Olivia de Havilland, of course, gives a stellar performance. Apparently she studied mentally ill people in the hopes of making her performances as realistic as possible—when a review scoffed at the idea of dances at institutions, she wrote the reviewer and told of attending just such dances. The movie produced a lot of change in how the mentally ill were treated, because no one wanted to acknowledge that people in their jurisdiction could possibly treat its mentally ill people like that.

Possibly the saddest character in book or movie, in fact, is Miss Sommerville (Jacqueline deWit), the former head nurse at the fictional Juniper Hill. She is now a patient. A young nurse in the book tells Virginia that Miss Sommerville used to be a crusader, but fighting for better treatment for her patients pushed her over the edge. She cared too much, the nurse says repeatedly. Virginia is sent to Occupational Therapy; she tells Robert that they’re doing things the hospital then won’t have to hire out. He calls her a cynic, but she’s not wrong.

Unlike many works dealing with mental hospitals, there are nurses here who aren’t sadists. There’s one who dislikes and mistreats Virginia on a level that feels personal, most mostly, they seem to just be tired. They’re doing very hard work, probably for not much pay, and they do not have enough to help anyone with. After a while, the women under their care probably seem a little less than real, just one more job to be gotten through before the day’s end. It’s harsh, but it’s understandable.

This is, frankly, the kind of movie I find hardest to watch, the kind of book I find hardest to read. Right now, I’m on medication that works for the first time in my life. Alas, it only treats one of my mental symptoms. (Plus giving pain relief, which is a delightful addition.) I’ve added a second, to treat another symptom (and also pain relief); so far, it is not working and is instead disturbing my sleep schedule and making me occasionally slightly woozy. Who can say if, eighty years ago, I might not have ended up in a place like Juniper Hill, with the treatments available there?

Next month, we’ll go into something a little more lighthearted, with the sequel to Freaky Friday—stay tuned for A Billion For Boris, and while I don’t actually ask for a billion, help fund the research by supporting my Patreon or Ko-fi!