I am, as astute readers will be aware by now, firmly in Camp The Book Is Usually Better. Not always. However, changes made to the book are frequently mistakes. Either something isn’t deemed filmable or they don’t trust the intelligence of the audience or someone just has a particular thing they’re really into that they’re going to shoehorn in whether it fits or not. (Looking at you, Giant Spider.) On the other hand, every once in a while, you get something where the original has good bones but is, on the whole, badly written and needs to be taken apart and put back together, and that’s what we’re looking at here.

Which is why we’ve hit the point where I have to admit I have never managed to finish the book. This time, I got all the way to page twelve. Which is astounding, because I’ve loved the movie since I was a child and they played it on The Disney Channel. I found a copy of the book at a library book sale when I was in perhaps junior high or high school. I was excited about it; I was by then already intrigued by the differences between book and movie. And the first difference here was that the movie is interesting.

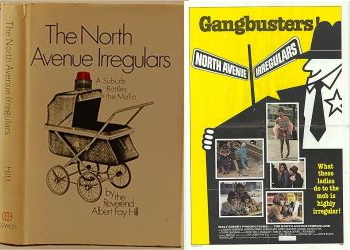

You’d think it’s a story that can’t go wrong. It is the true story of Reverend Albert Fay Hill, called Mike in the movie and portrayed by Edward Herrmann. He and his band of church ladies go up against organized crime. In the book, it’s in New Rochelle, New York; in the movie, it appears to be your bog-standard nondescript California suburb. In the introduction, Reverend Hill freely admits they didn’t take down the whole mob; that’s more than you can expect. But they did fight corruption in New Rochelle, at least?

The movie starts with a really superb cast. Edward Herrmann, of course, but also Patsy Kelly, Michael Constantine, Cloris Leachman, Barbara Harris, Ruth Buzzi, and even Alan Hale, Jr. Even the people I’m not terribly familiar with from other places are doing good work. They’ve simplified the story quite a lot—reducing the number of children he has, reducing the number of women involved in the story. It’s got a punchy script and a jazzy soundtrack, helped considerably by the rocking sounds of “Strawberry Shortcake,” the fictional band whose music was written by Al Kasha and Joel Hirschhorn.

It sounds as though the real Reverend Hill was a fascinating man. What he was not was a fascinating writer. Honestly, my biggest problem with the book was some unexplored bigotry. I’m not an expert on the subject and don’t know when “Negro” was out and “black” was in, but it’s a little jarring to initially discover the phrase “fat Negro” to describe a mob driver and later “Negro ghetto” to describe a section of the town Reverend Hill had previously worked in. I’m certainly not happy with how childish the women seem to be in his writing.

Not that the women are perfect in the movie, mind. There are six important female characters in the movie, leaving aside Mike’s daughter Carmel (Melora Hardin). Anne (Susan Clark) is the intelligent, capable secretary whose father was Mike’s predecessor at North Avenue and was forced to retire. Vickie (Barbara Harris) is a mother of, I don’t know, lots, who is doing her best for her country while also trying to parent, and the whole thing seems to take place in summer, too. Jane (Karen Valentine) is a bit flighty but also in the middle of planning a wedding, which would distract anyone. Claire (Cloris Leachman) is middle-aged and trying to not die alone. Rose (Patsy Kelly) is an older woman who still wants to be of assistance. Cleo (Virginia Capers) is arguably the best of the lot, and six Cleos would’ve gotten the whole thing done faster.

But repeatedly in those first twelve pages, Reverend Hill called them “girls.” I didn’t get far enough in to know how old any of them actually were, but either it was criminally irresponsible to get them involved because they were minors or else they weren’t girls. He also talks about how cool and professional he is and how the women are emotional and chattering.

Sure, Marv (Michael Constantine) from the Treasury Department finds the women exhausting, but he also is out of place before the women really get competent at what they’re doing. Even he has to admit that Cleo’s reliable, though her vehicles never seem to be until the end. The point is that, when they need to be reliable, for the climax of the story, they are. The movie also has the good sense not to put the payoff at the beginning; the only part I’ve read now is the part where they find the bank.

Next month, I promise I’ll try to get farther into the book, even though I’m stepping a bit out of my comfort zone. It’s another month where the book and movie have different names. The book is Twins, by Bari Wood and Jack Geasland; the movie is Dead Ringers, with Jeremy Irons and Jeremy Irons, not to mention one of the only credits for Jacqueline Hennessy. If you want to reward me for my efforts, consider supporting my Patreon or Ko-fi!