I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking, “Gillian, don’t you have enough recurring columns here already? Do you need another one?” And the answer is yes, because writing here means having somewhere to express the things I’d be thinking anyway. And one of the things I’ve been thinking is that it’s amazing how often I write about some movie no one’s ever heard of only to discover that it’s based on a book that not even I have heard of, and I’m writing about something I’ve loved since childhood. This isn’t something like, yes, Freaky Friday was a book first, because even if you haven’t actually seen Freaky Friday, you’ve probably heard of it.

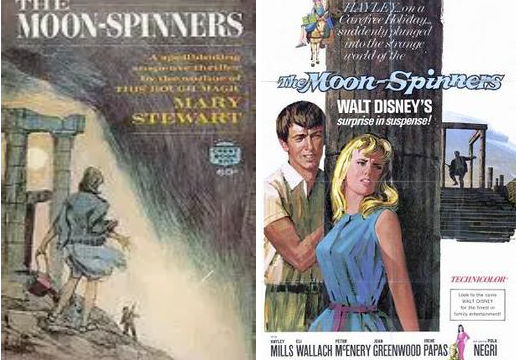

No, this week, we’re starting with The Moonspinners. It first came to my attention as a vehicle for Hayley Mills, the movie that was trying to show us that she had grown up since Pollyanna and The Parent Trap and could, say, have a romance while trying to foil jewel thieves. Clearly, it had limited success in that, as in most of my Disney fan friends haven’t seen it, no matter how wonderful I tell them it is. But years after I’d fallen in love with it, I encountered the original novel, by Mary Stewart, in a library book sale. I was already familiar with the concept of the novelization, and this clearly wasn’t a novelization. No, this was the original book, because it turns out there was one.

Both book and movie have the same approximate overarching plot. Nicola Ferris is on vacation. She visits the small town of Agios Georgios, where a man named Stratos is involved in the theft of fabulous jewels. A young man about her age is caught up in the middle of things, and she helps foil Stratos and meanwhile falls in love with Mark. A relative of an age to be her aunt looks on, concerned for her safety and amused by the progress of her relationship with Mark.

There are, however, distinct differences. Hayley Mills was seventeen or so when she made the movie; without expressly being said, it feels a bit as though the trip is a reward to her for graduating from high school. Book-Nikki has been working for a year for the British consulate in Athens and is in her early twenties. Aunt Frances (Joan Greenwood) is, well, her aunt; Book-Frances is a cousin who’s just old enough to be her aunt. Mark Camford (Peter McEnery) was a young courier from whom Stratos (Eli Wallach) stole the jewels; Mark Langley stumbled across a fight Stratos and his associates were having about the fencing of the goods from the Camford House robbery.

The movie also for the most part ruthlessly trims the cast list while simultaneously adding a few characters in other places. In the book, Mark is taking a tour of Crete with his fifteen-year-old brother, Colin, along with the boat’s captain—rapidly their friend—Lambis. Colin seems to in part be a casualty of casting Hayley Mills, simply because fifteen isn’t enough younger than her to make him completely unlikely as a love interest. He is for the most part shifted to become Alexis (Michael Davis), nephew of Stratos and daughter of hotel owner Sophia (Irene Papas). Who also helps fill in for the now-missing Lambis as a bit of local savvy who is definitely on their side.

Also gone is Tony, a Londoner who was partners with Stratos in his fencing business. The closest we get to him is British consul Anthony Gamble (John Le Mesurier), who fills out perhaps twenty minutes of the film by providing a way for Mark and Nikki to get to the next bit of plot. However, he gets a boozy and social-climbing wife, Cynthia (Sheila Hancock), and while he snaps to Stratos as one point that he does “exceedingly fine petit-point,” which is not quite the same as Book-Frances persistently referring to him as Little Lord Fauntleroy. Tony may compliment the appearance of Nikki in a pair of very tight jeans, but pretty well everything else about him is definitely subtext.

Meanwhile, the movie gives us the delightful Madame Habib, a role Walt personally talked Pola Negri out of retirement for. The book’s climax is exciting enough. But unfilmable in those days—Nikki’s swimming around the Bay of Dolphins in “wisps of nylon which — I suspected — had been almost non-existent as garments when wet,” which you’re not going to get Hayley Mills in. In the movie, Stratos is trying to sell fabulous emeralds directly to Madame Habib, who seems at least as interested in their history as their beauty. There’s a lot about her that we are not explicitly told; she’s definitely no better than she ought to be, as the saying goes. Also, she has a pet cheetah named Shalimar.

Another worthwhile change in the book is purely in the interests of spectacle, and I’m definitely okay with it. In the book, we eventually discover that Colin has been held hostage in a windmill. Sophia frees him—why is never entirely made clear, though it is crystal clear that she didn’t want him as a hostage in the first place—and helps him escape. In the movie, Stratos ties Nikki up and locks her in a windmill because he’s worked out that she knows what’s going on and is giving himself time to figure out what to do with her. Alexis (remember him?) tells her that, when they were kids, he and the other village boys used to ride the sails of windmills all the time, and that is how she’s going to escape. And she does. It’s filtered and a Hitchcock rip-off and works.

Often, my reaction to a movie that’s changed this much from its source book is confusion as to why they bothered basing it on the book in the first place, especially with as little name recognition as I’m sure the book had even at the time. Yes, all right, Mary Stewart (maiden name Rainbow, delightfully enough, and technically Lady Stewart because her husband had been knighted for services to geology) is a popular enough author, but the book isn’t mentioned on the posters. Mary Stewart isn’t on the posters in any kind of large print. This is not “this is a popular book that we have the rights to.” This is “we made a movie out of a book you probably haven’t heard of.”

For the most part, though, book and movie here seem to be designed to better fit their planned media. Book-Frances is a botanist and gardener, meaning Book-Nikki just mentions lots of different Cretan flowers—honestly, a properly annotated copy of the book would require lots of pictures. Movie-Frances collects songs for the BBC, so you get a roomful of Cretan women singing folk songs, meaning the audience gets to hear them. The characters trimmed make the plot simpler, for a 118-minute movie, and adding Madame Habib means there’s a glamorous yacht and a pet cheetah for reasons. Hayley Mills is a delightful Nikki, but she’s too young to believably have worked on her own in Athens for a year.

In the end, I can recommend both book and movie, and I think it’s possible to love them both for themselves instead of seeing the movie as a poor copy. I like Colin Langley in the book but strongly suspect he’d be insufferable onscreen. They both really strongly treat Greek as Other, even mentioning at one point in the book that a lot of people in Greek consider themselves “east of Europe.” I don’t know if that’s true; I don’t know if it’s true then. But it seems very clear that it’s true of the English people in the story, at least.

Next month, as proof that this column will not be completely about Disney, we’ll be talking about The G-String Murders, by Gypsy Rose Lee, and Lady of Burlesque, starring Barbara Stanwyck as Totally Not Gypsy Rose Lee! As it happens, I own The G-String Murders, as I already owned The Moonspinners, but obviously this is a column that I’m going to have to buy or rent a lot of things for. If you want to help with that process, please consider supporting my Patreon or Ko-fi!