And then she said, I got some news this mornin’ from Choctaw Ridge

Today, Billy Joe MacAllister jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge

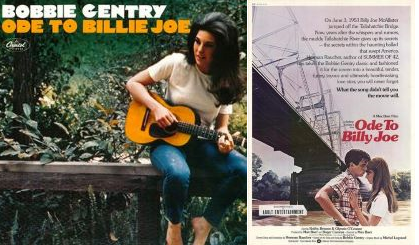

So begins Bobbie Gentry’s “Ode to Billie Joe,” later rerecorded for the film as “Ode to Billy Joe.” (She apparently insisted the original title was a misprint.) I’ve owned the book for years, though my copy gave up the ghost recently, but what I guess I never noticed was that it’s a novelization. Still, we might as well consider the song—once popular, now relatively obscure—to be our original today, though we’ll also be for a rare occasion touching on the novelization and how it handles the expanded world of Billy Joe MacAllister for the wider story.

The bare bones of the song are simple enough. The nameless narrator lives in the Mississippi Delta. On the third of June, she comes in from chopping cotton to dinner with her family. Her mother tells her casually that Billy Joe MacAllister, as quoted, jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge. The family sits around, eating dinner and calmly discussing the matter. The narrator says nothing, and her mother eventually notices that she has no appetite. She also says the preacher had noticed Billy Joe and “a girl that looked a lot like you” throwing something off the bridge. A year later, life is very different, and yet it goes on.

We all know where the movie is going to take us. Still, it starts with the flirtations of our narrator, now named Bobbie Lee Hartley (Glynnis O’Connor), and Billy Joe (Robby Benson). She is fifteen and he is nineteen. She lives with her mama (Joan Hotchkis) and papa (Sandy McPeak) and brother James (Terence Goodman) in a town so small Rural Electrification hasn’t gotten there yet. Her father won’t permit her to have “gentleman callers,” but she’s in love, or at least lust, with Billy Joe. Who has limited patience with “but Papa says” but is stuck madly deeply in something with Bobbie Lee.

The movie must cope with two things the song does not tell us. Things Bobbie Gentry specifically didn’t want to reveal in it. The movie must tell us what they threw off that bridge and why Billy Joe jumped. That he is will not be considered a spoiler, because it’s in the first verse of the song; the answers to those two questions are, and while we will, for a change, get to them, we’re going to deal with Gentry’s feelings on the subject first. She doesn’t have a problem with the choices made for the movie, but she will not reveal if they have anything to do with the apparently true story the song’s based on.

Gentry’s point, it seems, wasn’t what was thrown—that is included mostly to make it clear that the narrator had a connection with Billy Joe—or why he jumped but that Mama and Papa and the in-the-song-nameless brother show no awareness of the narrator’s pain. She isn’t eating, but no one puts it together with her loss of someone she cares about. They say casually cruel things about Billy Joe, and the narrator must either put up with it or explain why she chooses not to. As Persia pointed out in her fine article on the song, there is a clear parallel with the narrator’s own lack of concern about her mother’s pain in the last verse.

Of course, the movie can’t just leave it at that without some really creative storytelling. It could have been done, and I can think of a few ways how, but it would be narratively unsatisfying in a 106-minute movie as opposed to a four minute fifteen second song. So we get the story of how Bobbie Lee and Billy Joe knew each other as children. His parents are apparently death to farms and have drifted for years, and they’ve drifted back into the town. He remembers Bobbie Lee and is immediately in love, or something, with her, and they get as close to doing something about it as it is possible to get in a small Baptist Mississippi town in 1953 while still saying on the right side of God and local morality.

There is one night where everything goes wrong. Exactly what goes wrong is spoiler territory, so be warned, because we’re going for the spoilers. Because I have no doubt some of you are wondering why I who have been consistent for years in my Pride columns am choosing to write about this particular work in June.

The movie gives Bobbie Lee an imaginary friend. As a child, she had a cowboy doll named Benjamin, and as a lonely teenager, she continues to talk to him. The doll lives in her hope chest; Benjamin still follows her around as an imaginary presence, giving her the kind of advice she knows she’d be getting from Brother Taylor (Simpson Hemphill). After a music festival, Billy Joe disappears for two days, and Bobbie Lee sees him. He agrees to meet her the next night to tell her what happened to make him run off. The next night, she meets him, having brought Benjamin, the real doll of Benjamin. Who, in a fight, goes off the bridge.

This is not why he jumps. The night of the music festival, he got very drunk on moonshine he probably thought was beer. He almost used the services of a sex worker, but he was too drunk. The movie shows him wandering off; what he eventually tells Bobbie Lee is that he had sex with a man. He will not name the man; the movie does at the end, but his name doesn’t matter. What matters is that it is 1953. Billy Joe doesn’t seem to have disliked the experience. And he is afraid that it means he is forever ruined for Bobbie Lee, whom he still loves intensely.

I mean, do we expect a 1953 Mississippi lumber mill worker to have heard the word “bisexual”? We do not. Of course we do not. And, yes, Billy Joe MacAllister jumps off the bridge into the ranks of Dead Movie Gays. (For the purposes of which we’ll count bisexuals; the closest the movie gets to either term is “men like that.”) It’s not great. On the other hand, you can understand the reasoning of the character. Especially since it’s a ridiculous Southern Gothic. The novelization is funny and melodramatic all at once—and available, as is a bad VHS copy of the movie, on the Internet Archive—and makes the unnecessary decision fit at least a little with the motivations behind it.

I enjoyed the movie more than I did the last time I watched it, enough to have barely enjoyed it. I love Robby Benson for reasons having nothing to do with this movie, but this is not the best example of his acting. And he’s about the best-known person in it. The movie feels as though it was inadvertently made to be a cult classic in queer circles, and so far as I know—I’m not exactly in queer circles, after all—it is not. There are speeches that seem born for quoting ironically. Why am I the only person I know who can even a little?

Next month, we’ll be back to family fare with the frankly almost as absurd Dear Lola, also known as The Beniker Gang. I have owned the book and read it over and over again; I may have some bits memorized. Help me out if I have to pay money for the movie by contributing to my Patreon or Ko-fi!