The issue with writing about westerns is that there’s just so many of them: John Ford made over 100 films in his day, sometimes three a year, and there is thus a nameless sea of unnamed obscure men who made their short, sturdy westerns that rode through poverty row and turned a profit solely by virtue of their cheapness. There are the traditional auteurs of the western genre like Ford and Leone, then there are those famous filmmakers who made a couple westerns in their day–Fuller, Hawks, Walsh, Peckinpah–and then there are the myriad nameless journeymen who, like their heroes, show up to the desert one morning, do their job for a couple weeks or less, and then ride outta town with their pay.

Thank goodness that some film writers have done their part to rescue Budd Boetticher from the same obscurity as these other sand pebbles – the six or seven westerns he made from ‘56 to ‘60, starring Randolph Scott and produced by Harry Joe Brown, represent one of the most wonderful strides of the classical era, more remarkable for how little they have been remarked upon. What’s present in these films is a significant signature, a worldview wrapped up in a formal approach, and a particular thematic fixation. Buchanan Rides Alone is the middle film of the Boetticher/Scott stride, and very much the middle child. It lacks the mysterious endings of The Tall T and Ride Lonesome, doesn’t possess the virtuoso sentimentality of Seven Men From Now nor the creeping despair of Decision At Sundown. It is, in a word, typical, in that both what it has and what it lacks make it the perfect test case for the Boetticher brand.

First thing’s first: filmmaking is defined by its limitations. In the case of Boetticher, that limitation is time, both in the sense that his films were sometimes shot in just ten days, and that not a one of these westerns runs longer than 80 minutes–in fact, Buchanan Rides Alone is one of the longest ones at 78. This brevity wasn’t uncommon to B-films, but Boetticher combines it with a deliberate and creeping pace, allowing for lots of silence and waiting, looking, and bluffing. What’s cut out of his films is not dead air but rather dead weight – there are no subplots, no extraneous characters, and no time wasted on anything but the main character and his conflict. Buchanan Rides Alone is one of Boetticher’s only filmswith a consistent and coherently-sketched setting, the town of Agry, afforded perhaps by those extra five minutes (one can imagine an early scene, where Buchanan strolls through the centre of town and gazes at the signs of all the businesses, being cut in an even less “loose” film). But even then, every detail has a payoff, however surprising. When Buchanan asks “ain’t there anybody in this town that ain’t an Agry?” it can be taken as a meta-commentary of the script’s raw efficiency.

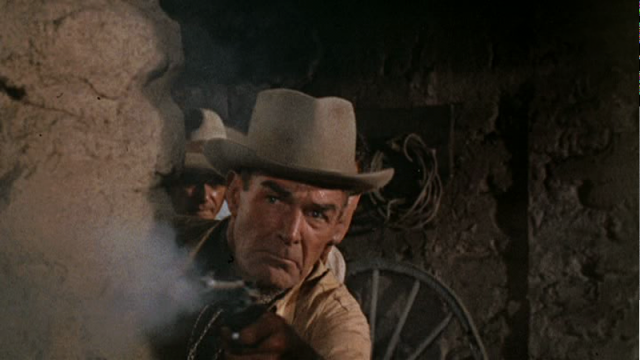

But the Boetticher filmmaking style isn’t just found in relentless pacing. His filmmaking is not organized around dialogue or action or even setting, but around gesture (indeed, the gesture of both the camera and the performers). The way he lingers on Randolph Scott’s every turn of the head and move of the hand is what distinguishes him from every other B-Western journeyman. Every movement of an actor is a new piece of insight to either their inner world (for example, the hint of confidence with which Buchanan pushes Roy Agry’s finger away in the early bar fight, our first hint that Buchanan’s easygoing attitude is not a naïve one) or the outer world (in an early scene, the hotel clerk ducks down to the register to make change, revealing an AGRY FOR SENATOR sign, the first sign that something is truly amiss). All that we need to know about a character is conveyed in how they walk through a wide shot, Buchanan’s strolling straight ahead most frequently juxtaposed with Amos’ unsteady and awkward running, back and forth (as critic Fernando F. Croce notes, Amos’ indecision becomes a literal running joke). When your sets are all backlots or deserts, and you’ve only got so many shots for one day, the gestures have to do as much talking as possible. Instinct is everything.

Can the cowboys of Randolph Scott be amalgamated into an archetype, the Boetticherian Protagonist, driven by a unifying virtue? Unlike Ford’s heroes, who were driven by tradition, and Hawks’, who were driven by professionalism, Boetticher’s men are driven more by instinct and reflex than anything abstract. This is perhaps why his films feel so minimalist and tactile, and perhaps why the Boetticher men have such a high degree of elasticity. Buchanan is completely unlike the pitiable heroes of Seven Men From Now, Ride Lonesome, much less pathetic than the hero of Decision at Sundown, but not quite as capable as the protagonists of The Tall T and Comanche Station, none of which are as easygoing as Buchanan. But here are two things that all these men have in common: they’re simple, and they’re lonely. Boetticher’s villains are ultimately more complex than his heroes, again, all in different ways: Lee Marvin in Seven Men From Now and Richard Boone in The Tall T are themselves two of the greatest villains in Western history, and the villains of this film are in another class altogether, even for Boetticher.

Usually, there is the big bad and his league of cronies, all fodder for an ending gunfight. This time, there is a network of power, a hereditary autocracy smack on the border of the land of the free. The Agrys control their town like monarchs of a medieval fief, who have a stranglehold on the economics, the laws, and their enforcement–and therefore basically all the power. Their rule is so entrenched that Buchanan’s status as both an individual and an outsider is sufficient to topple the whole house of cards. We see the machinery of the Agry legal system work when Buchanan pays for both his ten dollar steak and ten dollar hotel room too conspicuously, and once Amos clocks his stash of cash, his death sentence is certain before they can pin anything on him. It’s one man (and later a group of Mexican revolutionary allies) against the Agry machine. And lest you confuse this anti-authoritarianism for populism, look at the baying mob of bloodthirsty Agrians clamoring to see a hanging outside the sheriff’s office.

The opening scene of dialogue between Buchanan and the sheriff of Agry is a particularly wonderful microcosm of Boetticher’s banter-bargaining-bluffing standoff, so nonchalant that it first goes unnoticed. After introductory shots of Buchanan riding from the border into town, we get a view of Agry’s main street from the porch of the sheriff’s office, and a door made of iron bars swings over our field of view. Then, on the left and right of the frame, the sheriff and Lou stand, further trapping Buchanan in the background, overwhelming the frame with silhouetted entrapment. Despite this, the conversation carries on, with the sheriff stubbornly demanding that Buchanan descend from his horse, and Buchanan refusing until it becomes clear that he must come down. Even when being threatened with being shot, Buchanan’s cheery demeanor doesn’t flinch, and he descends from his horse going behind one of the men in the frame, out of view, finishing the composition. In this one scene, which changes from an establishing shot to an over-the-shoulder to a conversation without ever cutting, we’ve been told every single thing we need to know about this film–a once free town has been imprisoned by the corrupt law enforcement, and one figure in the centre of this imprisonment, through sheer force of his easygoing nature, is a threat to it. The entire film blossoms from this initially cheerful standoff, from “I can hear you fine from where I’m sitting” to “I don’t wanna shoot you off that horse” and finally to “I wouldn’t want you to!” Boetticher is a filmmaker of impulses and reflexes and pregnant glances, which is what makes his standoffs so palpable and intense.

I’ve mostly spoken about the ways that this film is typical of the Boetticher style, so I’ll end by talking briefly about the ways that it’s different. Most Boetticher films are not this relaxed, and most aren’t this absurdly repetitive. Buchanan always seems to be getting sprung and then captured again, funny at first, then tiring, then borderline existential. Most Boetticher films are funny, but most don’t have such a gregarious hero and none have such a flair for banter – this is the closest he ever got to Rio Bravo. Finally, most Boetticher films have at least some place for the other half of the population, but the only woman in this film exists to get slapped in a saloon by Lou Agry in the first ten minutes of the film, and then never be seen again. In Boetticher’s universe of gestures and impulses, women represent sensitivity and vulnerability, they offer the fleeting possibility of another life for our lonesome riders. Without women, Buchanan Rides Alone has no chance of measuring up to Boetticher’s masterpieces and has no chance of making the viewer feel anything beyond suspense, laughter, and gut satisfaction at the perfect timing of a move.

Still, though, those pleasures are present in spades, and this film serves as a strong baseline for Randolph Scott’s cowboy persona and Boetticher’s formal approach. Watch this film to be primed for this style of western, and then wade deeper into Boetticher’s westerns. Every one of them is at least this good, many of them are far, far better, and they all point to a filmmaker who found a way to make identifyiable, personal films under the constraints of time, money, genre and audience. Budd, like his cowboys, did his job without thinking too hard about it, relying on quick thinking under the clock, with only his instincts to guide him. Boetticher rides alone.